From the outside, Royleston Home for Boys in Glebe looks like a majestic Victorian manor, with magnificent arched windows and a sweeping veranda. Yet behind the facade, the secrets of hundreds of young boys were hidden for almost 60 years.

Child slave labour, beatings so severe many were left with permanent disabilities, horrific sexual torture, being told they were unwanted and nobody loved them —these misplaced children were under the watch of a middle-aged couple, entrusted to care for young children.

With as many as a dozen different names, including Royleston Home for Wayward Boys, the home was established to provide accommodation for boys who were wards of the state waiting to be placed in foster care.

Public perception — encouraged by a variety of scurrilous names — was that the inhabitants were delinquent criminal juveniles. However the reality was most boys were abandoned by their parents through hardship or misfortune.

Such was the loathing of the home by locals, the boys were kept locked away with limited or no access to education and it was common for the word ‘imprisoned’ to be used when describing the boys who lived there.

“I’ll never forget being told about a little boy who had just arrived at Royleston,” says Leonie Sheedy, the CEO of the Care Leavers Australasia Network (CLAN).

“He was led down to the backyard where he saw twin boys sitting in a sandpit. He stood there watching them when one of the twins looked up and asked him if he would kill them both.

“Can you imagine? How wicked must things have been to have to ask another child to end your life and your brother’s life?”

CLAN represents, supports and advocates for people who were raised in children’s homes, foster care and orphanages.

Sheedy says all too often she hears dispicable stories about the boys who lived at Royleston during the 1920s up to the 1980s, revealing their stolen innocence.

‘WHY ARE WE ALWAYS BEING PUNISHED?’

“I remember the first day like it was yesterday,” says Geoff Meyer, who was at the home during the 1940s. Meyer had been a ward of the state since he was 17 months old.

“I was four-and-a-half years old and the squeal of the front gate opening was like someone screaming.”

Meyer recalls how punishment was dished out regularly and with vigour.

“In the dining room, the food wasn’t cooked and the porridge had weevils in it. But if any of us vomited it up, we were forced to get on the floor and to lick it all back up again. And this was done by adults in charge of our care. We never really thought about it then, but thinking about it now, you wonder why the hell did they do this, how could they do things like that to little kids?”

Meyer says the boys weren’t allowed to talk to each other, they didn’t even know each other’s names and they weren’t allowed to protect each other — although Meyer says he feels lucky because there was one ritual he was “saved” from on occasion because of his tender age.

“During bath time the bigger boys were forced by the supervisors to squeeze the testicles of the younger boys, and they would bet on who would scream the loudest. There was an older boy who wouldn’t hurt me — just pretend to — but I would scream my head off making out he was squeezing me. I was lucky because, believe you me, it hurt bad.”

Meyer says Royleston was a place where you were always in trouble, always being punished for something.

“I remember thinking why are we always in trouble? You would either be flogged or put underneath the stairs for up to three days without food water or toiletries,” says Meyer.

“You were shunted in there, in pitch darkness for days. Sometimes on your own, or with a couple of other boys. We weren’t allowed to talk so we would sit in the dark and hold hands.

“What was my crime to deserve this? What I did was report sexual abuse by one of the matrons. I kept complaining and crying, so that was my punishment. I was only seven at the time.”

SEXUAL ABUSE: ‘I PASSED OUT FROM THE PAIN’

Meyer recalls being so young, he didn’t understand what was happening when he was sexually abused.

“The matron took me into her room and said to me ‘I am your new mother’. I had never seen my mother, but I had heard other children talking about their mothers so I thought ‘oh this is great, I’ve got a mummy now’. The matron said this is what mothers do with their sons. I can remember those words and I didn’t know why back then, but I felt what she was doing to me was wrong.

“People back in those days were sadistic, maybe they still are. What that matron did to me was so excruciating I passed out from the pain.”

It was shortly after the abuse began that Meyer was sent out to a foster home where the woman in charge noticed him was hunched over in pain.

“I arrived at her place and I admitted to her that my wee wee was sore. She said ‘well you better give me a look then’. She took me to the doctors first thing as I had contracted a serious infection.”

When he returned to Royleston, Meyer was thrown under the stairs again.

“I kept complaining to the superintendent about the matron sexually doing things to me. But because I kept whingeing she decided to lock me in up in the dark for three days. It was terrifying. It’s a wonder us kids didn’t come out mental.”

Dr Michael Davey was placed into Royleston when he was about four years old when his mother was deemed to incapable to care for him and his four siblings.

“There were men who came to the institution because they knew boys were there and they came to abuse them,” says Davey.

“I heard stories about men who took boys away for the weekend, with no checks into who they were and they would abuse those boys in any way they wanted to, and then those boys would come back to Royleston, just stunned as to what had happened. We all told the authories about the abuse, but we were never believed.”

‘I DIDN’T KNOW THE FACTS OF LIFE’

Ron Arthur was about seven years old when he was sent to Royleston and his first impression was being confronted by a towering 12-foot fence with barbed wire running around it the back yard — no wonder the general public considered them ‘inmates’ and feared their existence.

‘I was given an old pair of shorts and a shirt to wear but no shoes,” Arthur said in an interview for the Forgotten Australians oral history project.

“We used to cop it every night. If you peed in the shower you got the strap. It was cold water, as there was no hot water. Because it is only natural, when the cold water hits your body, you automatically wee. Whack! across the posterior.”

With emptiness, Arthur speaks about the repeated sexual abuse that occurred at Royleston.

“I didn’t know what he was trying to do. I was so young at the time, you know, you don’t understand those things. I didn’t know the facts of life.

“They had a loft and there was this man, he was a paedophile and he interfered with me in that loft. I reported it to the super, but he said ‘oh deal with it’. But a week later that man disappeared, apparently he was moved to another kids home. He was never charged. I think other boys probably complained, but it was all kept secret. The super said ‘don’t tell any of the other boys about it’.”

Arthur weeps as he recalls what happened, “He penetrated my backside and I cried out, I yelled out.”

Realising no one was going to help him, Arthur tried to run away, but not having anywhere to go, he was quickly captured.

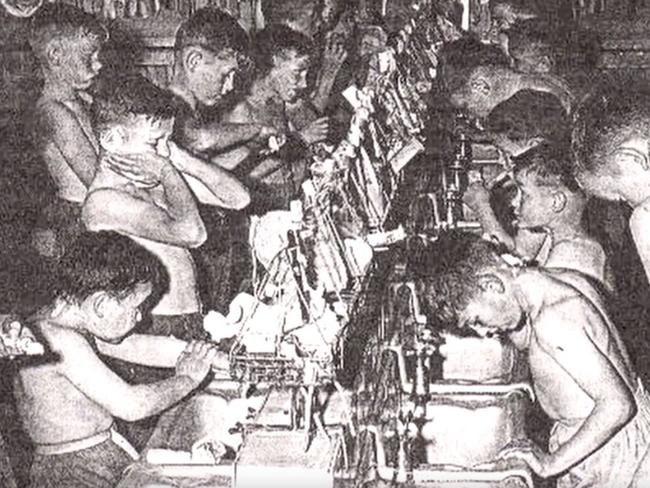

CHILD SLAVERY AT ONE OF AUSTRALIA’S MOST-ICONIC BRANDS

Arthur could sense the foreboding punishment upon his return to Royleston, but he could not imagine how grim it would be.

“The super said to me ‘you’ve been a bad boy. You ran away. Well it’s all right, we know a place you can go. A place in Casula. A big chicken place.’

“I thought at the time that was good because a few other boys who had run away, when they were caught and returned, they would disappear during the night and I would wonder where they got to. Turns out some of them were sent to Parramatta asylum. Poor lads.”

Arthur continues, “They sent me out to Mr Wally Ingham’s property out at Casula. There were half a dozen other boys from the home, wards of the state as well.

“Our first job was at 5am, that was to make the food mix for the chooks. We had to carry the feed in big kerosene cans, to the chook pens, and then after feeding all the chicks, we had to go around and pick up all the eggs.

“I was there for a seven months and it was constant work. After you picked up the eggs you had to clean the pens, after you finished that you had to go to the next pens.

“It was the same work every day. No time off. It was a seven day a week job. Never a day off. and it was all state ward boys. There was no payment at all. I never received one red cent.”

Inghams chickens were approached for comment and sent this statement on November 15:

“It is impossible not to be moved and saddened by what we have read in the article. However, Inghams Group Limited today is a modern, listed Australian agri-company and there is no one in our company with any knowledge of the tragic experiences shared in the article. Therefore, we feel it would be inappropriate to make any formal comment.”

‘I JUST WANTED SOMEONE TO LOVE ME’

Insight into the depravity occurring in the home was revealed in 2004, during a senate inquiry into institutional care for children.

The inquest bared the heartbreaking testimonies of more than 500 wards of the state, detailing their gut-wrenching experiences in government-run institutions.

“I was trying to get some caring or love from anyone,” one of the Royleston boys, who wished to remain anonymous, told the inquiry.

“I remember talking to the laundry lady and trying to get some caring from her but it seemed that all the adults in the place were totally cold to the children.”

The feeling of abandonment suffocated the boys as soon as they walked through the doors, as this submission to the inquiry revealed.

“I was sent to Royleston Receiving Depot for Boys. It makes us sound like animals doesn’t it? Societies rejects. Children rounded up and herded into depot’s where we could be sorted, placed and hidden away and forgotten about.”

“It was the institution where you were first taken until they decided where they would permanently place you. I soon realised that this was no longer a game. I did not like being at Royleston and I wished that I were back in my tent. For some reason the home always felt cold and I was always scared and hungry. I was told that I was sent there for my own good and that I was going to be there for a long time so I had better get used to it. If I was sent there for my own good then why did they treat me so bad?’

ESCAPE WAS JUST A MISNOMER

The compulsion to run away hung over they boys heads as some kind of salvation.

Meyer says he planned his escape with three other boys and was euphoric as they scuttled along the roof and jumped down onto the sports oval next door. But those feelings were short-lived. “We ran for our lives,” says Meyer. “We got about 500 yards from the home, tearing across the park in Glebe and then we sat on a bench seat.”

Catching their breath they looked at each other.

“We said ‘what the heck are we going to do now?’ We didn’t know where we were. Then two police officers found us and we told them we had run away from Royleston.

“They asked us why and we told them what was happening up there, about the treatment at the home. They took us back and one of the officers said they would have this all stopped. But as soon as we got back, we were put straight underneath the stairs. All of us.

“We were there for three days. When we came out the boss said with a wry smile that the nice police officer was his brother. We don’t know whether he was or not, but there was no report or record made of it anywhere. I was about seven-and-a-half years of age.”

Davey says the trauma the boys experienced was evident in their behaviour. “Because we were under so much stress we often wet the bed and we would lie about it to avoid being whipped. I would say, no I just drooled a lot. We all tried to find the best way to cope that we could, to survive.

“A number of the boys would cut images of women out of magazines and would keep them and pretend that they were their mothers and say how much their mum loved them.

“Every child just wants to be loved by a parent. And we were, for reasons that some of us couldn’t understand, we were abandoned.”

‘NO ONE BELIEVED US’

As a result of the 2004 senate inquiry, the Forgotten Australians report was created, exposing brutal treatment so severe, children died from their injuries.

“With the level of physical assault that has been reported in evidence, it is highly probable that within a group of 500,000 over many years some deaths would occur as either a direct or indirect result of these assaults,” the report reveals.

“While the Committee only received minimal anecdotal and circumstantial evidence, there remains a suspicion of a pattern of limited investigation by police or authorities, no inquests, and police or authorities accepting unquestioningly the word of the carers in relation to deaths occurring at their institution.”

Sheedy says only a few have been made accountable for their criminal behaviour while employed at Royleston. “For most of the boys, who are now in their 80s or 90s, they will never face the courts, so their abusers have gotten away with their crimes.” She says not enough has been done since the 2004 inquiry. “Even today when you try to get justice, you try to take on the Department of Community Services, they will put you through the ringer, to discredit you, to minimise what happened to you. They say you were already damaged before you entered the system,” says Sheedy.

CLOSING THE DOORS FOREVER

By the 1970s, as fostering became less common, boys stayed longer in Royleston and it became over crowded.

Royleston was closed in 1983 and then served as offices. It was sold by the government in 1993 to a family who restored the house to a private home.

Former DOCS officer, Morri Young was a departmental officer responsible for supervising the manager and staff at the boys home institution from 1981 to 1983. He says, “It was a miserable, dark and cold place, with very little good to say about it. I was pleased to have a small part in its closure.”

Mr Young says it was his mission to shut the home down after his first visit. “Royleston stood out as being the worst in terms of mismanagement and mistreament of children. The managers showed me nothing to indicate they cared for the home or for the boys.

“The manager had been a taxi driver in London before he took up Royleston. He was a cold, withdrawn and cranky man. He was disdainful and rejecting of children’s welfare,” says Young.

“The boys weren’t allowed access to welfare officers, to any family, they weren’t allowed to participate in any activites and they suffered horrific punishment. At 18, if they hadn’t run away, they were given a train ticket and booted out the door.

“The managers were outraged when it was closed down. They had previously been rewarded for budget control, for keeping the home out of the newspapers - any adverse reports coming out - so they thought they were doing a terrific job. They felt betrayed by the government, that was the mentality,” says Young.

SWEPT UNDER THE CARPET: ‘WE HAVE REMAINED FORGOTTEN’

One of the greatest challenges now for the children who were in institutional care is to access their files. “It’s a fundamental desire of any child to know who their parents are, to know if they have family,” says Sheedy.

Yet it is almost impossible due to records being scattered among the States and held in various government departments that take years to respond to requests for information.

Sheedy explains, “A lot of records have been destroyed and there is no central place to access information.”

Another factor is the torment for those who had been mistreated so badly by the government to now approach them for help.

Davey, who is an author, motivational speaker and youth advocate recalls reading his DOCS file. “I had tears rolling down my face,” he says.

“When I looked at my file there was an overwhelming sense of the absence of my family.

“There were memories of being raped by boys, by men who were supposed to be my family, being whipped by belts, then sent packing because I was crying or because I wet the bed.

“The tears came because of the regret, the sadness, about what had happened, but also about what might had been. To see my life in front of me was confronting.

“I suffered 12 years of depression, I almost took my life. But I was given a gift of having hope for the future. I thought something good must be around the corner. I have just got back from riding around Australia to raise money for kids with cancer and that was a bit of a extrapolation of those types of feelings I had as a child, to never give up. It’s not easy to ride a pushbike for over 14,000kms and sexual abuse is hard to live through, but you can,” says Davey.

Last month the Federal government announced survivors of institutional child sexual abuse will receive up to $150,000 under a national redress scheme.

Social Services Minister Christian Porter said the Royal Commission into Institutional Child Sexual Abuse estimated that 60,000 children were sexually abused.

Mr Porter said a telephone helpline and website to provide information on the scheme would be available from March 2018, that is assuming Labor backs the legislation.

However, given the limits of the Commonwealth’s constitutional powers, the next key step would be the states backing the scheme.

“It is essential that all government and non-government institutions are held accountable and take responsibility for providing redress to those people who were harmed in their care,” he said.

Sheedy says it is CLAN’s mission for the care leavers to be granted redress from the government for the loss of family, culture and for the loss of their childhood.

“People like us were deemed to be second-class citizens. We were told your own parents don’t want you so no one else wants you. You will end up in jail, you are a no hoper. No one will love you. You crush a child’s self-esteem and there is no one else to balance that out. You don’t feel entitled to go to the authorities, and those brave ones who did weren’t believed.

“The whole nation is responsible for this. They didn’t care about children like us and we were hidden from society and we have remained hidden and forgotten.”

Care Leavers Australia Network 1800 008 774

Lifeline Australia 13 11 14

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

‘Devastated’: Childcare bans take toll on our 20,000 male educators

Male early childhood educators in NSW say horrific sexual abuse claims, and kneejerk restrictions enacted by operators, are “the straw that broke the camel’s back” to quit their jobs for good.

Mark Latham’s explicit texts from the floor of NSW parliament

Embattled independent MP Mark Latham exchanged graphic and sexually explicit WhatsApp messages with his then-partner while sitting in the parliamentary chamber, according to a bombshell log of text messages obtained by The Daily Telegraph. Warning: Graphic language