‘What happened to you?’: Missing Persons registry on mission to get answers to coldest mysteries

At the start of Missing Persons Week, the NSW Police unit dedicated to solving the most challenging cases appears to be learning from its predecessor and making strong strides.

NSW

Don't miss out on the headlines from NSW. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- Hewson defamation case against Grimshaw, ACA goes to court

- Revealed: First NSW prison case imported from Victoria

At the start of Missing Persons Week the newly minted police unit, dedicated to finding almost 800 long term lost people, is determined not to repeat mistakes of the past.

New statistics, released by the unit, appear to show they’re making good on their promises to find answers for restless families.

Inside a room at the NSW Police headquarters, the faded portraits of 769 long term missing people endlessly flash on screens, looming over the officers tasked with some of the most difficult investigations in the nation.

NSW Police, one year ago, dissolved the Missing Persons Unit acknowledging it was beset by problems and needed to change.

MORE NEWS

Body modifier who inserted snowflake in woman applies to stop trial

‘No evidence’ 2yo girl was attacked at Lollipop’s: Police

Perish brother who plotted to cut up police informer paroled

The new Missing Persons Registry, under Chief Inspector Glen Browne, moved to modernise how both old and new cases are handled.

The former senior homicide investigator says missing persons cases are now treated like potential homicides and must be investigated “as thoroughly as possible”.

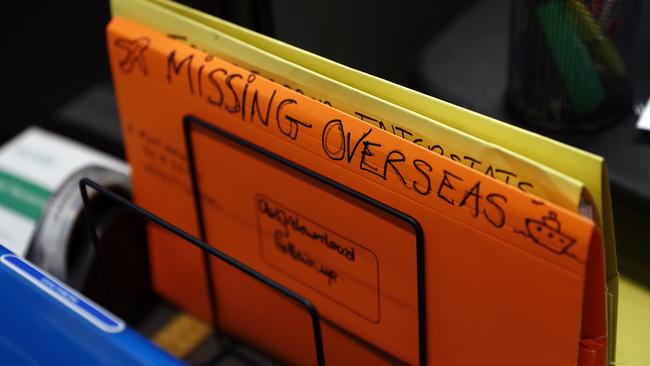

The first step toward breakthroughs in old cases, he told The Daily Telegraph, was to collect countless scattered pages, folders, boxes and rooms of investigation files and digitise them so they could be searched.

“Part of what we did was to digitise everything and, with a review process, try to work out if we DNA on file, dental records, things we should have,” he said.

The review of cases found 11 people who had been reported missing but had gone on to reinvent themselves and start new lives.

“People are allowed to disappear if they choose to,” Insp Browne said.

“We can‘t legally tell family members where a missing adults turns up. We are obliged to say they’re safe and well - but can’t tell them any more.”

When Insp Browne took the registry’s helm he hung the screens around the room.

“You cannot help but look at them and it drives you,” he said.

“I wish I knew what happened to every single person.”

But the mistakes of the past - incomplete records, lost documents, missed opportunities - are equally

impossible to escape.

A resolution in every case is an impossible dream and much of that rests on the shoulders of police, the commander says.

“We can’t hide from that,” he said.

“At the moment we have a string of various coronial missing persons cases where our response wasn‘t up to standard.”

He’s reviewed cases personally that weren’t “done thoroughly” and, years later, have become difficult barriers.

It’s frustrating but it’s just a reality of keeping notebooks and papers in cupboards and basements for decades.

“I try not to be too critical of investigators from older times,” Insp Browne said.

“It would be unfair, but the primary role of the new registry is to see nothing slips the cracks again and we don‘t repeat mistakes of the past.”

A seismic change has been in the way police at the front counters of all police stations handle missing persons reports.

The registry becomes involved instantly, rather than waiting 90 days for someone to be declared “long term missing”.

Each year NSW adds, on average, 76 new names to the list of the missing. This year, the commander proudly says, there have been just seven so far.

Four of those were lost at sea so only three people, as of the start of August, have gone missing on land.

“We knew we needed to do it better,” he said.

“We are striving to make the best missing persons registry and unit in the country and I like to think we are well advanced.”