Westfield heiress Betty Saunders-Klimenko's journey from orphanage to a life of luxury

THE heiress to the Westfield fortune tells her story - how an orphan, conceived in a jail cell, became one of the country's richest women.

AMONG the bearded behemoths in grimy green trench coats, the girls with mullets and undersized tank-tops, surrounded by the smell of petrol wafting around Barbagallo Raceway's pit-lane, Betty Saunders-Klimenko looks like any other V8 Supercar fan.

But Betty, with her heavily tattooed arms, black boots and purple hair, isn't just another punter.

She is an almost-billionaire who is at the dusty track in Perth's northern suburbs to see her Erebus Motorsport V8 team compete in the fifth round of the V8 Supercars championship.

The heiress to the Westfield fortune tells her story- how a blue-eyed orphan, conceived in a jailhouse cell, became one of the country's richest women.

► WESTFIELD TITAN SIR FRANK LOWY'S $33b SELL-OFF TO FRENCH

► BETTY KLIMENKO'S STUNNING BATHURST 1000 VICTORY

CELL NO. 3

The drug-addicted prostitute clung to her baby: "Not again. Not this time." Anne Neil had already given away three children, an unfortunate by-product of her business, abandoning them all shortly after birth, unloved and unwanted.

But this one she wanted to keep.

Betty Saunders-Klimenko was conceived in Cell No.3 at Kings Cross police station.

The officer who arrested her mother became Betty's father - sad, sick, but true.

Betty, inked arms folded as she nestles into a leather recliner on the back of a truck used for transporting race cars, says bluntly: "I was a product of the Kings Cross jail. My father found his way into the cell and I was conceived."

"Apparently my mother had three other girls and put them all up for adoption straight away. But for some reason she wanted to keep me."

Neil vowed to change after giving birth to Betty. The former Miss West Australia took her baby home and went about beginning a new life.

It didn't last. Seven weeks later Betty was abandoned, dumped in an orphanage. "Thank goodness," Betty says, flicking her purple fringe from her brow, revealing childish eyes, brilliant and blue.

"She saved me. I can't even think of where I would have ended up if she didn't take me to the orphanage on that day. She dropped me on the floor and said 'I don't want it'."

Betty knows little about her biological mother. A sepia photo is the only reminder of the woman who left her all alone.

"I never met her," Betty deadpans. "It took me a long time to even try to find out about her. I hired a private investigator not too long ago, mainly for health reasons to see if I had any biological risks. I know she was Miss West Australia.

"I have a photo of her, an old black-and-white one given to me by one of my biological sisters. She had the Marilyn (Monroe) type hair and blue eyes. It is a dim picture but you can see she was pretty."

Neil was long gone when Betty learned about her - dead at a young age.

"Apparently she helped three men escape from Goulburn jail," Betty says. "And three months later she was found dead of an overdose."

"She was a heavy addict, addicted to opiates, whatever she could get in her day."

Betty knows even less about her father, the copper who went beyond the call of duty.

"He came to Australia at an early age and was a Vietnam veteran. He arrested her and obviously found his way into her cell. That is all I know about him, really all I want to know."

That is where the story of Michelle and Betty's father ends. Well almost. Betty looks down at her stumpy hands. "Dad was six-foot-five and my mother was almost six foot," Betty says. "By all rights I should be tall. But I am not and it is because I was a drug baby. I was addicted to whatever she was on when I was born and the drugs have shortened all my extremities. My hands are stunted. So are my fingertips, knees and toes.

"My body, my torso, is that of a six-foot woman, but my limbs are of a dwarf. I am only five-foot-three.

"I am also allergic to formaldehyde. My hands, my throat, they swell up. I am allergic to all root vegetables. I can't go near drugs like cocaine. I would be dead if I ever did that."

But don't feel sorry for Betty - she has an estimated family worth of $960 million.

And this is how she got it.

THE SAVIOUR

John Saunders was handed a 10-pound note as he walked off the boat. He looked at the money and smiled. "I am going to make it big," he grinned.

Saunders had travelled 16,000km to escape his horrors. He boarded the boat to Australia with nothing but the shirt on his back and Eta, his bride, by his side.

Saunders considered himself lucky. He had survived the Holocaust.

Locked up by the Nazis when he was 18 - his crime, listening to the BBC - the Hungarian Jew spent more than five years in a German concentration camp.

He worked his way into favour by scrubbing boots and washing dishes.

And he survived - unlike his father and brother who were gassed in Auschwitz. Saunders and Eta married just before heading off to Australia in 1950.

But Eta, after hiding in a sewer for two years to avoid capture, couldn't become pregnant.

That's when they met Betty.

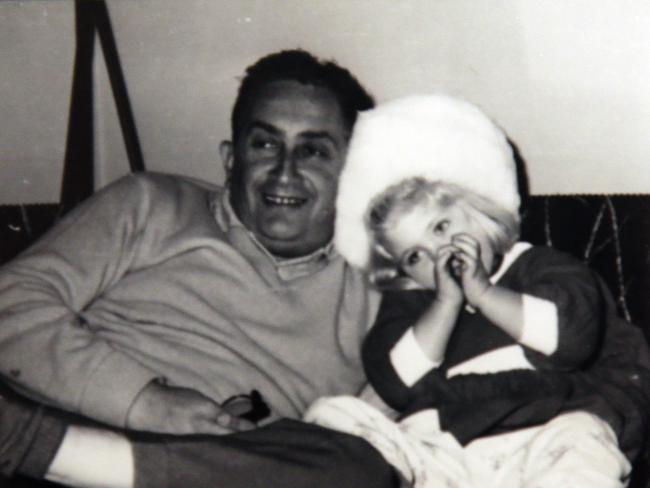

"It was 1959 and John Saunders walked into the orphanage," Betty says. "He had picked him a child, a dark-haired boy with Mediterranean looks, just like him. But then he saw me. Blue eyes, blonde hair and a girl, I was giggling in my crib. He took one look and told them he wanted me."

In a twist of fate, she was taken home by a would-be billionaire. Talk about luck.

"He said he liked my sense of humour and chose me." Betty says. "It was a spur-of-the-moment decision that saved me from who knows what? A life of pain."

Baby Betty wasn't well. Her blue eyes hid her pain.

"I was a drug baby," Betty says. "I was probably giggling because I was delirious and having withdrawals."

Those blue eyes sparkle as she talks about her adoptive father, the man who changed his name from Jeno Schwarcz to John Saunders.

"He was an amazing man who dreamt big," she says. "Dad was a political prisoner when he was just 18 and he was in a concentration camp before it became a concentration camp. He worked hard. But he also took risks.

"He smuggled scraps of food to other prisoners. He was moved from camp to camp, but luckily he avoided Auschwitz. Dad never got the tattoo, he was in before they started branding them. But he was scarred for life.

"He later spoke about the horrors when he built the Sydney Jewish museum. I went with him to the opening and saw all the photos and he told me what happened and what he went through.

"He made me look through them all and told me what ones he witnessed. "That was something I will never forget. Something I can never forget."

THE EMPIRE

Almost a teenager, Betty stormed towards her father. "Dad," she demanded. "Are we millionaires?"

Saunders looked at his daughter, his brow furrowed in surprise.

"Why?" he replied. "Why do you want to know that?"

All serious and surly, Betty continued: "Because all the girls at school are telling me that we are millionaires. Do we really have a million dollars in the bank?"

Saunders smiled. "Yes," he said. "We have a million dollars. Tell them that if you like."

Saunders' empire was already rising when he adopted Betty. After arriving, the budding entrepreneur went about buying and selling whatever he could.

"He worked as a packer in a store as soon as he arrived," Betty says. "He also grew mushrooms under his house and did whatever he could to survive. He read all he could, taught himself English and saved almost every dollar he earned.

"He eventually had enough to buy himself a delicatessen."

That is where Saunders met another Hungarian immigrant, a man called Frank Lowy.

"Dad was someone that lived by his watch," Betty says.

"He was always where he had to be two minutes before he had to be there. He hated people that weren't on time. Frank Lowy was one of his delivery boys and he was always on time. He was the only person he knew that was on time.

"Frank was younger, but they shared a similar past, and Dad liked him. Out of the blue, Dad asked him if he wanted to go into business with him. Neither of them had money, but they found a way to start a coffee shop in Blacktown."

Frank Lowy, born October 22, 1930, lived in Budapest, Hungary, during World War II.

Like Saunders, he spent time in a concentration camp, then was imprisoned in Cyprus, fought in the Arab-Israeli war in Galilee and Gaza, before leaving Israel for Australia. He was delivering smallgoods when he met Saunders in 1953.

"They just hit it off," Betty says. "They were very similar and had the same work ethic."

They would soon strike gold - the mother lode.

"Dad was a guy that kept his eye on the newest things," Betty says. "He saw what they were doing in America and wanted to do it here. The newest thing in America was the strip mall with a roof.

"We had shops on streets here, but none of them were indoors. Dad and Frank went to every bank and they said 'No'."

It was the Bank of NSW that finally backed their new business idea.

Betty says: "They were in a field in the western suburbs when the bank told them they needed a business name. 'We are in a field,' Dad said. 'And we are in the west. So we will call it the Westfield.'"

With the backing of the NSW bank and a property business worth $30,000, Saunders and Lowy officially listed the Westfield Group on the Australian stock exchange in 1960 and an empire was born. Westfield Group is now the world's biggest shopping centre operator with 119 malls across four countries.

"The company has assets under management in excess of $63 billion.

But all that meant nothing to Betty, who despite her father's growing wealth, lived a modest childhood.

"I don't ever recall that we had money," Betty says. "There wasn't one moment when I sat back and considered us to be rich.

"At first we lived in an apartment on Blues Point Rd (in North Sydney). I was there until I was five. And then all of a sudden we had a new house in Cranbrook Rd (Rose Bay).

"I suppose that is when he had some money. It was about 1964."

AM I ADOPTED?

Betty Saunders never suspected a thing. But maybe she should have - her blonde hair, those blue eyes, were a dead giveaway.

"There were clues," Betty says. "But I was too young to notice.

Betty was playing in Frank Lowy's yard when she was about eight when a fight erupted. "What would you know?" Peter Lowy, the son of the other shopping centre tsar, screamed. "You're adopted. You came from a home."

Betty ran up the stairs to her mother and father. Betty says. "I just looked at Dad and screamed, 'Am I adopted? Peter said I am adopted'."

Saunders shrugged and said: "Yes you are." He turned and continued his conversation.

" I didn't care," Betty says. "I was just pissed off that I lost the argument with Peter. I thought nothing off it then. They were my parents and it changed nothing."

Others would bring it up later, when $1.1 billion was on the line.

TEEN ANGST

They say money doesn't bring happiness and Betty will vouch for that.

John, her beloved father, all but disappeared when she was 10.

She had to make appointments at the Pitt St head office of Westfield just to see her Dad. She was largely raised by nannies.

"I was in trouble every 15 minutes," Betty says. "My Mum died when I was 10 and it was hard - really difficult for me, but even more so for Dad. Mum died from cancer and it was a horrible. She died in pain.

"Dad became a workaholic and never left the office. I had to grow up with nannies because he was never home. They didn't care about me.

"I remember leaving for school and Dad was already gone.

"I would come home and he was still at work. I would go to bed without seeing him. I would only see him when we took a holiday, or sometimes on a Sunday when he wasn't playing tennis with friends."

Betty was 15 when her father remarried.

"It was hard with my next mother," Betty says. "She was 25 and I was 15. I could have been her sister.

"Dad was 52 at the time, and the dynamic was just wrong. I think she tried hard in the beginning but we just clashed.

"I was 19 when they had my sister and could have been her mother. Things weren't great between us."

That isn't to say she never had fun with her stepmother. Betty and Saunders' wife were once mistaken for prostitutes and hauled into a room by security guards.

"Frank Sinatra walked out," Betty says. "He looked at us and told the guards that we didn't look like hookers. He grabbed a picture and signed it for me before sending us on our way. It was a classic."

But Betty does not look back fondly on her teenage years.

"I was a rebel," Betty says. "I guess I really didn't know who I was.

"I was born a Catholic but was brought up Jewish, and I didn't really feel accepted.

"I would find out why later. I went to an Anglican school, SCEGGS, and battled through those years. I spent a lot of time alone, nights in my bedroom."

Betty was put to work at a young age. Despite the money, her father imposed his strict work ethic.

"I started working when I was 13," Betty says. "I was Santa's little helper in the shopping centres. I wore the red skirt, the white fur."

And then later, I was the first woman to work in the men's jeans department at Grace Brothers.

"I always worked. Whether it was on my father's office, or cleaning rooms in his hotel, I had a job. He made me work for everything I had.

"I was serving a woman in the hotel at a Christmas party and she didn't like the service. I walked over and asked her if everything was OK. 'This is a disgrace,' she said. 'I know John Saunders and I am going to tell him about this.'

"I grabbed a glass of red wine and 'accidently' spilled it on her. 'That is it,' she said. 'I am going to call him now and have you fired.'

"It was about then someone leaned over and whispered something into her ear. She went white having found out he was my father."

THE SPLIT

Saunders stared at his daughter, his jaw clenched, his fists in a tight ball. "If you marry him it is over," he said. "You will no longer be my daughter."

Betty had announced her intentions to marry Daniel, 11 years her junior, and the conversation that followed saw her leave the Saunders family's Rose Bay mansion for a tiny house in Matraville.

"He told me if I went out the door I wasn't coming back," Betty says.

"I bawled and turned my back. Walked out of the building. Walked out of his life."

Betty had already been married and had two children.

"I never had any Jewish friends as a teenager and I felt obliged to marry the first Jewish man I met," Betty says. "Herman was 10 years older than me and I felt pressure to marry him. I went out with him and I just said 'he will do'. It was actually my stepmother that set us up.

"I think part of it was that I wanted to move out of home and I couldn't do that until I was married. We were given a house and set up with everything I could want.

"It wasn't a great marriage. We were married in 1981 and were separated in 1986.

"I don't regret it because we had two beautiful children."

Betty didn't care about the money. She was willing to sacrifice all she had - and all the money she was going to get - for a soft soul with a golden heart. "Daniel was 19 when I married him and I was 30," Betty says, as her tattooed and tanned husband stands at the back of the V8 truck going a slight shade of red.

"We got hitched in Las Vegas. We ended up getting married in secret and of course Dad was furious. He cut me off from everything."

Betty was shunned from the family and sent packing with nothing more than the clothes on her back.

"I went from being a rich princess who had it all to a nobody who had nothing," Betty says. "But you do funny things for love.

"I had money, had a secure future, but I just knew I had to spend the rest of my life with this boy. And back then he was a boy, but I knew he would become a good man."

Betty had never ironed. Had never washed clothes. Her new working-class life shocked her to the core.

"I went from having limitless money to earning $19,000 a year," Betty says. "I remember standing out the front of Coles waiting for the expired meat to come out because we couldn't afford to eat.

"I soon learned what it was like to have nothing."

Saunders would not speak to Betty.

"It was horrible," she says. "I had lost him. I would call his secretary and she would put me through.

"He would pick up the phone and listen to me but he wouldn't say a word. Still, I stood my ground. I loved Daniel and I wasn't leaving him for the world."

THE RECKONING

One day Saunders picked up the phone and called his cousin in Israel. He thought it was just another call to his friend, the Jewish figure he respected above all.

It wasn't.

"What is this problem with your daughter I keep on hearing about?" the cousin asked.

"He is not Jewish," Saunders said. "And he is almost half her age. I can't accept that."

The cousin thought for a moment, the line silent.

"Is he a drug addict?" he asked.

"No," Saunders said.

"Does he beat her up?" the cousin asked.

"No," Saunders replied.

"And how does he treat her?" the cousin asked.

Saunders thought for a minute.

"He treats her like a princess," Saunders said.

The cousin was blunt: "Well you are a fool. Go and find your daughter and tell her that you love her. She is doing nothing wrong."

The reunion coincided with the birth of Betty's third child.

Again Saunders walked into a cold, white room and found his girl.

"He just walked in to the hospital and picked up my child," Betty says.

"It was like everything was OK again. And that was pretty much it. I knew our relationship was repaired."

Life changed in an instant.

"I think he ended up respecting me for standing my ground," Betty says. "I was a tough woman as he was a tough man. I gave up everything for what I believed in and I think he knew that he would have done the same. He eventually told me that in his own way."

Daniel proved his love - not that he needed to - by converting to Judaism. The couple were married a second time.

John Saunders died in 1997 at age 74. His death shook Betty. "It took my sister and I 10 years to work out the will with the trustees," Betty says, not particularly comfortable talking about the extraordinary amount of cash it contained.

"It was very complicated, as you can imagine with that amount of money. We had many issues with trustees and things like that."

Betty won't talk about it but she eventually got her share of the fortune. "I didn't know how much money he had until he died," she says. "And when I found out I was like 'holy crap'. It was ridiculous.

"Dad was worth more than $500 million when he died and by the time the will was settled the amount was over $1 billion."

Betty won't say what her share was, but she is easily one of Australia's top five richest women, even though the BRW list doesn't include her name as she is said to have "family wealth".

It was valued at $960 million at last count.

"I like to play down what I have," Betty says from the back of her truck. "But I have more than enough. I live in Vaucluse and have everything I could ever want.

"I was very much a kid in a candy shop when my father died.

"He was a person that frowned on excess when he was alive.

"I can remember visiting him in the hospital with a sparkle coat. 'Nice jacket,' he said. 'How much did it cost?' I told him $200 and he hit the roof. Frank Lowy was there and he had to calm him down, telling him that was actually cheap.

"I let loose a bit after he died. I bought things I never had and overindulged my children.

"Daniel had to pull me back."

Life was good. Great.

LOSING HER RELIGION

And then everything came crashing down again - her stepmother spat out a hurtful truth that would see Betty question everything.

"She told me I wasn't Jewish," Betty says, the V8 thunder cracking in the distance. "She told me I was never converted.

"I went screaming to the rabbis, asking them if it was true. They looked up the records and sure enough she was right.

"I should have been taken to the synagogue when I was taken home, but I wasn't. My late mother didn't keep a kosher home and they wouldn't do it.

"I was devastated - all I knew and had lived by was gone.

"I ran to the Rabbi in a state.

I asked him what it all meant. He told me that I was a good friend of the Jewish community.

"It hurt me more than when I found out I was adopted. I lived my whole life thinking I was something, followed it for 37 years, and it was all stripped from me in an instant."

Betty never regained her faith - not the one she had spent her life following anyway.

"I didn't convert," she says. "That no longer made sense to me. I am a spiritual person and I do believe in a high power and that there is something more.

"But I do it my own way."

THE HEIRS

Daniel, the love that almost cost her a fortune, tucks her into her bed. He kisses her on the cheek, pulls the blanket up to her neck and tells her that he loves her.

It is all a woman could want.

And that is why Betty doesn't regret a thing.

"Daniel is the most loving man anyone could ever meet," she says.

"He is the type of man every girl wished they could have and he still tucks me in every single night. He changed my life.

"I was 150kg when I met him, and I would weigh 250kg now if it wasn't for him.

"He met me and told me I was his beauty queen and that nothing else mattered. He loves me."

So let's get to the money.

How much does she have and what does it mean? And how are the tattoos, tracky-dacks and trailer-park look received in a privileged live of Prada and polo.

"I have copped it my whole life," Betty smiles. "People think I am a bogan until they find out what I have. Women used to come up to me when my kids were at school.

"They would say 'you think you could dress better with the amount of money you have'.

"I would say 'look around sweetheart. Look at people like the Triguboffs. We don't have to dress like we have money because we do have money'.

"You can do whatever you like. That is the good part of having money. There is plenty of bad."

Betty knows she is unique.

Getting her first tattoo when she was 47, she is now covered in them.

"I am somebody that shocks," Betty says matter-of-factly. "I have tattoos, I have pink hair, but that is me. I make no excuses for that because that is the person I am."

Daniel laughs when asked about his wife.

"Sometimes I just have to let her go," Daniel says.

"We spend every minute together but sometimes I just look at her and say go for it.

"Betty does some pretty crazy s ... sometimes. There is no doubt that we are different. But we are real people. What you see is what you get."

But Betty's money has also cost her several friendships.

"I have lost about $20 million giving money to friends," she says.

"I gave one person $6 million for a business that failed.

"I get asked for money every day and it gives me the s ... . - everyone thinks they have an idea I have never heard of and they all want something. It makes it hard to have friends."

That doesn't mean Betty doesn't sometimes indulge.

She has hired the Choirboys to play on her balcony and forked out $500,000 to buy Daniel a Lamborghini.

But the craziest thing she has ever done is buy a V8 Supercar team.

"Daniel was given driving lessons with a car he bought and that is where it all started," Betty says. "We caught the motorsport bug and now we have a V8 team. I am semi-retired and I am putting everything into this team (Erebus Motorsport V8 team)."

Betty knows that she was smacked in the arse with a rainbow.

She thinks about the boy left in the orphanage all the time.

"There is a boy out there that could have had my life," Betty says.

"I feel sorry for him, but it was my fate. I have been asked what I would say if I met him and I have thought about it a lot.

"And I would tell my mum 'thank you' because he saved me from her. I know what it would have been like if she had kept me - and what it would be like if my father John had never found me. I feel comfortable knowing that he doesn't know what he missed out on.

"It has been an incredible life."