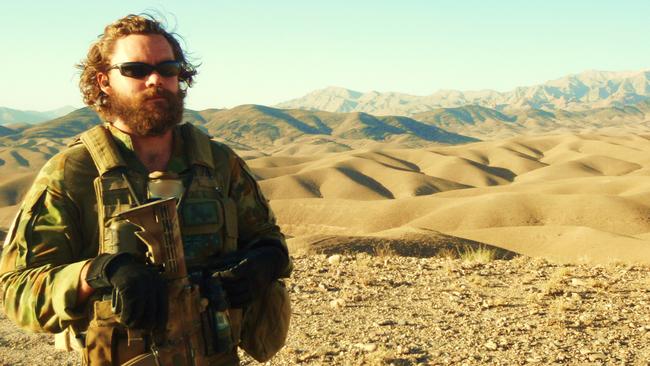

Voodoo Medics endure extreme and intense training to save lives in the kill zone

To their Australian special forces teammates, a Voodoo Medic is the “trump card” on the battlefield. Their elite training is “a guarantee that we’re able to deal with any situation,” said Bram Connolly, former platoon commander and Afghan veteran.

NSW

Don't miss out on the headlines from NSW. Followed categories will be added to My News.

TO the special forces they deploy with, a Voodoo Medic is a “trump card” on the battlefield.

Their elite training is “a guarantee that we’re able to deal with any situation,” said Bram Connolly, a former platoon commander and veteran of several Afghan tours.

“If you’re shot in Afghanistan there’s a higher likelihood that you will survive that than if you were shot in the streets here in Sydney.”

For Major Connolly, the proof came when his forces were outnumbered and outgunned at the battle of Zabat Kalay on October 18, 2010.

When several soldiers went down in the first minutes, including one that had been shot and another scalped by shrapnel, Corporal Tom Newkirk went to work.

“I guess it’s a traumatic event having to treat somebody whilst getting shot at, but we train so hard and long that when it happens you’re very well prepared,” he said.

That day Newkirk treated two category-A injuries — one commando had been shot, another scalped by shrapnel.

“They were probably the most intense and required the most concentration at the time,” Newkirk said.

“It sounds odd but when you have to provide care in these situations you are excited to be able to provide that care should you be competent.”

Kilos deploying with special operations are beyond competent having completed 18 months of initial medical training before undertaking intensive tactical medicine and pre-deployment training at SOCOMD.

After being posted to the command they undertake a three-week special operations rescue course where their skills from basic training are turbo-charged as they learn advanced surgical procedures, advanced pharmacology and how to manage patients for extended periods.

They are also trained to perform land, water and air rescues during gruelling 20-hour days of training in realistic environments under similar operational stressors such as sleep deprivation and no days off.

Civilian first responders including police, fire and ambulance also provide training to the medics in a range of skills including how to perform vertical rescues and save car crash victims.

By the time medics deploy they are like a paramedic and GP rolled into one.

Medics also undertake courses designed to provide them with the skills — such as fast roping and close quarter combat — to work within special operations.

Most of the current training for medics within SOCOMD has been implemented in the last five years as a result of lessons learned on the ground in Afghanistan.

Major Dan Pronk said that a component of his training had been Tactical Combat Casualty Care, which he described as “down and dirty medicine”.

“It is aimed at applying a minimum of life-saving interventions with brutal efficiency, whilst also focusing on neutralising enemy threat and completing the mission at hand,” he said.

“We were pumped through two intensive weeks of TCCC training, by day and night, starting with simple, single-casualty scenarios, and culminating in a night mass casualty scenario.”

Dr Pronk, who deployed to Afghanistan four times and went out on more than 100 combat missions with our special forces, said the tactical medicine techniques were programmed into the Kilos’ muscle memory.