Voodoo Medics — Part 7: Coming home to ‘normal life’ can be the toughest battle

THEY are elite fighters, operating in high performing teams with a powerful sense of purpose — until the day they discharge from the military. All of a sudden veterans are at home, thrust back into “normal” life with families and domestic duties. WATCH THE DOCUMENTARY SERIES NOW.

NSW

Don't miss out on the headlines from NSW. Followed categories will be added to My News.

THEY are elite fighters, operating in high performing teams with a powerful sense of purpose — until the day they discharge from the military.

“Then you get out and you’re at home washing the dishes, taking the dog for a walk,” said Major Bram Connolly, who spent more than 20 years in the Australian Defence Force.

“You’re no longer in a Blackhawk at night racing across the desert with someone yelling out ‘30 seconds’ before you’re running out and getting shot at and you’re shooting back.

“You can’t even explain how amazing that job is.”

All of a sudden veterans are at home, thrust back into “normal” life with families and domestic duties. For many, the initial transition back into civilian society is fraught.

It is at least equally true for the Voodoo Medics, the elite group of medical specialists who accompany our special forces into combat whose stories are revealed in The Daily Telegraph series.

Because of the nature of their work, even seasoned special forces operators say the medics see the worst of the trauma on the battlefield.

VOODOO MEDICS

By the time Major Dan Pronk, a former doctor within Australia’s Special Operations Command, was discharged in 2014, he felt like he had merged with his role of combat doctor.

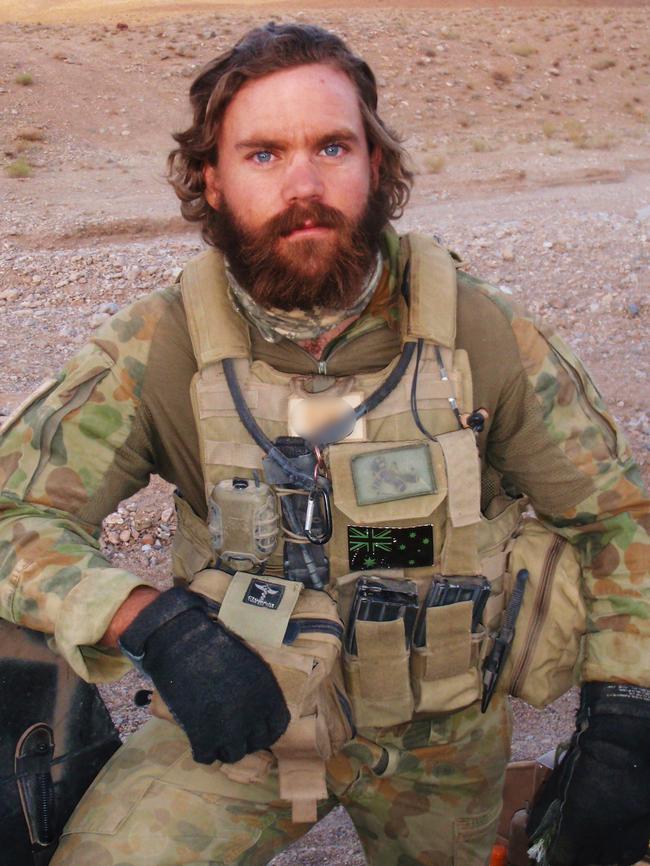

“I cut my hair down into a Mohawk and grew a goatee beard,” he said.

“I guess outwardly I felt myself being one in the same with that role of the combat doctor, just operating purely mechanically in that function. All emotion was removed from myself at the time to keep going.

“Anyone looking at special ops from the outside, all you see is the shiny stuff — the go fast stuff, the action, the painted rifles, the bearded operators, the ballistic sunglasses — but like any of these things the reality of it is very different.”

That reality included the violent deaths of three comrades within weeks during his second deployment in 2011.

MORE VOODOO MEDICS

Voodoo Medics: Dan Pronk’s military man cave was a ‘cathartic project’

In separate incidents, Sergeant Brett Wood died from an improvised explosive device blast on May 23; Sapper Rowan Robinson was killed by a Taliban sniper on June 6; and Sgt Todd Langley was shot dead on July 4. Pronk was there for all of them, and could not save them.

“Initially I was adamant that I was never going to go back, but that didn’t last at all,” he said.

“I went back to work and, before I knew it, I was busting to get back there.

“I felt that if I could get back to Afghanistan and actually respond and save one of our guys that that would somehow help me process the events of the blokes that I couldn’t save.”

It didn’t turn out that way. In fact, things quickly went from bad to worse.

“Within weeks of being back on the ground the (Special Operations) Task Group lost another bloke that I was mates with,” he said.

“No one had been killed since I left, then I turned up again and we’d lost another task group member.”

SASR Sergeant Blaine Diddams was hit in the chest while leading a mission to capture a Taliban commander in the Darafshan Valley on July 2, 2012.

After those four deaths and the birth of his third son, Pronk and his wife decided it was time for him to step away from the role he had spent his career chasing.

“When I first got out of the army I felt like a fish out of water. I just couldn’t associate with the people that I found myself around,” he said.

“I fell into the trap of maybe drinking a little bit more than I should have with the goal of trying to be able to get to sleep and have a decent night’s sleep without the intrusive thoughts and dreams.

“In hindsight I realise what I needed to do was rebuild my self worth in something new.”

Dr Pronk unplugged from his old career and set about re-establishing himself in a new job. He became a doctor in an emergency department in Queensland.

He also started an MBA and took on passion projects to keep his mind busy

Pronk, now based in Adelaide, says successful transition can be a long road.

“I’d gone through that somewhat dark period and a degree of post traumatic stress but also that loss of identity together really led to a bit of a bad patch,” he said.

“As I got more and more distance from the events I found that the intrusive thoughts and the physical reaction to those intrusive thoughts was getting less and less.

“I experienced this strange transition whereby I started to view things differently.”

He said the trauma he faced in Afghanistan gave him a new appreciation of life.

“Losing mates in the field in Afghanistan — that was now my bad,” he said.

“I started just really experiencing post traumatic growth.

“I found myself a whole bunch more positive than I had been prior to those experiences.”

Commando Chad Elliott was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder and was medically discharged from the army after being shot through the leg and hit with shrapnel during an ambush on his second tour of Afghanistan.

But he rejects the idea that he is a victim.

“I probably think of myself as a survivor and a fighter,” he said.

“I survived that incident but I’m not letting it affect me in the future.

“I’m continuing on, I’m still trying to progress and reach my goals.”

Elliott, now married with two sons, said that despite the physical limitations left by his wounds, his goal is to obtain a black belt in Brazilian Jiu Jitsu.

“My headspace at the moment is … I have days when (it’s) pretty bad.

“Having my family helps and doing my daily BJJ training is probably key to me staying sane.”

A spokesman said the ADF was unable to provide a breakdown of PTSD diagnoses by regiment or battalion.

However, the results of the most recent study in 2015 found that 8.7 per cent of serving ADF members self-reported symptoms of PTSD.

Corporal Mark Donaldson VC, who worked closely with Pronk at the SAS, said a big part of dealing with the trauma of war was actually enjoying the job.

“There seems to be this feeling in society that if you go away to war that you have to come back with some kind of problem, issue, something’s wrong with you, PTS,” he said.

“It’s unpalatable for people to say ‘you know what? I actually enjoyed that’.”

“It was extremely unfortunate that some people got injured, wounded and died. It really is. That’s horrible.

“However, I still stand by the fact that I enjoyed it, I loved it, and a lot of us did — we really did — and I don’t think we should ever be ashamed of that.”