There were no outward signs of trepidation on the part of Jamal Khashoggi as CCTV footage captured him entering the Saudi Arabia consulate in Istanbul.

But the journalist, former intelligence aide and dissident would have known within moments that his worst fears were being realised.

Bundled into an office, according to Turkish intelligence, Saudi-born Khashoggi was set upon in front of the consul general, Mohammad al-Otaibi, by members of a 15-man hit squad.

He befriended Osama bin Laden and tried to bring him back into the fold

Beaten, injected with a paralysing agent and then taken to an adjoining room, he was then allegedly dismembered while still conscious.

The torture and killing was captured in minute detail and attributed to Khashoggi’s Apple Watch, but it is more likely Turkey had the consulate bugged.

Khashoggi, 60, had planned to pick up paperwork confirming his divorce so he could marry his Turkish fiancee Hatice Cengiz.

He left her sitting forlornly outside the consulate with instructions to go to authorities if he did not emerge.

And so it was, he never did.

After his death, it’s believed Khashoggi was cut up by a forensics expert who, in a grim Australian connection, studied at the Victorian Institute of Forensic Medicine in Melbourne after being sponsored by the Saudi government.

Khashoggi’s remains were then divided into boxes and smuggled out of the country, possibly under diplomatic protection, on a private jet back to Saudi Arabia.

So far, so gruesome.

The Saudis have publicly denied any involvement but privately are said to be preparing an admission of some kind.

But Khashoggi’s murder was no ordinary killing by a brutal regime that routinely jails, tortures and even beheads activists, human rights campaigners, and clerics who might represent a threat to the stability of the House of Saud.

Instead, it was a targeted hit on foreign soil against a US Green Card holder and Washington Post columnist — not someone whose disappearance would go unremarked, or who lacked friends in high places.

In other words, the operation was a big risk for whoever ordered it, even as a close ally of the West.

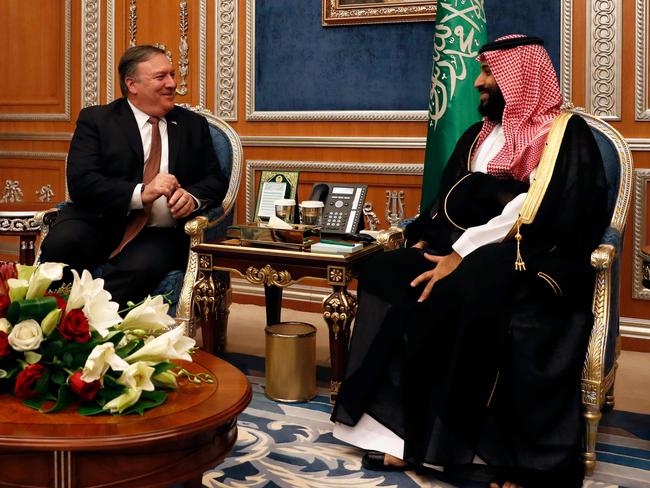

Signs increasingly point to Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, the de facto ruler of the country, who has tried to present a reforming face to the world while cracking down harshly on dissent at home.

Which leaves just one question. Why?

Just what was it about Khashoggi that made him such a threat to the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia — or at least a faction of interests within it — that he became the target of a 15-strong hit squad sent to Turkey by private jet to carry out the mission?

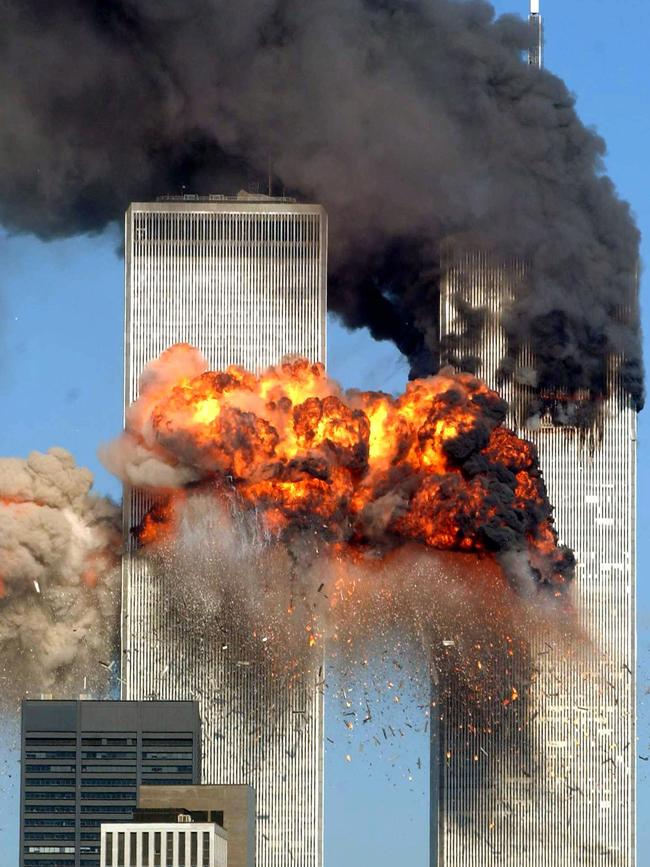

Much hinges on the answer to this mystery, from the fate of reform efforts in the puritanically Islamic Saudi Arabia to who becomes the dominant power in the Middle East. Even, potentially, answers to enduring questions about how much the Saudis knew about the terror attacks of September 11, 2001.

“There have been reports that he may have had some secrets about 9/11 and possible Saudi involvement,” says Professor Amin Saikal, author of a number of books on the Islamic world and director of the Centre for Arab and Islamic Studies at the Australian National University, who cautions that at this point “they are just reports but that may have something to do with it”.

Either way, he says, “they might have seen him as a more dangerous individual than he might have been”.

Which would go some of the way to explain why someone within the Kingdom took the risk to go after Khashoggi.

After all he was, for much of his life, the ultimate Saudi insider — even if his later career as a critic of the regime saw him pose as an outsider.

The nephew of Adnan Khashoggi, the Saudi arms dealer and middleman once thought to be the richest man in the world, Jamal Khashoggi was in the 1990s close to Prince Turki al-Faisal, the long-time head of Saudi intelligence, as he advanced his own career and interests.

Khashoggi would later become a critic of the government following intense internal power struggles between his patron and then-King Abdullah.

But his loyalties had been suspect long before this time, even as his knowledge of the Saudi royal family’s most intimate secrets, including their dealings with al-Qaeda, grew.

While studying in the US as a young man, Khashoggi embraced violent political Islam as espoused by the Muslim Brotherhood.

Later he would befriend Osama bin Laden — the scion of a vastly wealthy and well-connected Saudi family — and, it has been reported, try to bring him back into the fold.

This, some believe, would also mean that he would know about the extent of dealings between the Saudi royal family and al-Qaeda in the months and years before 9/11.

While long a subject of speculation, a major lawsuit filed by 9/11 survivors and their families in the United States alleges Saudi Arabia had knowledge of, and perhaps helped the terrorists plan, the attacks before they occurred: 15 of the 19 al-Qaeda hijackers were Saudi citizens.

The litigation is a potential diplomatic and public relations nightmare for bin Salman and his reform efforts.

Questions about whether Khashoggi had fully renounced his allegiances to the Muslim Brotherhood, and whether his push for reform in Saudi Arabia might have been a cover for plans to make the country more, rather than less, radical, hung over him.

In January Khashoggi had registered a group in the US state of Delaware called Democracy for the Arab World Now (DAWN) — a human rights advocacy organisation aimed at promoting the Arab Spring democracy movement.

“Victims of the Arab world’s authoritarian regimes seek leadership from the US and DAWN intends to provide such leadership,” a core statement about the group says.

As recently as last August, Khashoggi would use his Washington Post column to claim that the US had got it wrong about the Muslim Brotherhood.

“The United States’ aversion to the Muslim Brotherhood, which is more apparent in the current Trump administration, is the root of a predicament across the entire Arab world,” Khashoggi wrote.

“The eradication of the Muslim Brotherhood is nothing less than an abolition of democracy.”

But whatever threat he posed, it is increasingly considered that his death was the result of a spectacular miscalculation or over-reaction by bin Salman.

The evidence is strong that bin Salman himself took out the hit. Overnight Thursday, leaked surveillance footage showed a member of bin Salman’s private entourage entering the consulate shortly before Khashoggi’s murder.

The man, Maher Abdulaziz Mutreb, has reportedly also been seen in the background of photographs taken during the Crown Prince’s recent trips to the US, France and Spain.

Although regarded as a social reformer in the West, bin Salman has, since coming to power, led a drive against Muslim Brotherhood clerics; at least three are facing the death penalty for their supposed associations with the group.

But should bin Salman be proven to have given the order to kill Khashoggi, it may come to be seen as the latest in a long line of blunders by the Crown Prince, Lowy Institute research fellow Rodger Shanahan says.

These include, Shanahan says, bin Salman’s costly fight with Iran-backed Houthi militias in Yemen, which he initiated in 2015 when he was the Kingdom’s defence minister. (There are now 10,000 dead in that war, tacitly supported by the West.)

There is also Saudi Arabia’s unresolved dispute with Qatar, and August’s diplomatic feud with Canada, which saw trade frozen, students recalled and Ottawa’s ambassador expelled after Canada’s foreign minister tweeted about the detention of human rights activists in the Kingdom.

Such missteps add to bin Salman’s vulnerability within the Kingdom, where rival factions within the Saudi royal family live in a constant struggle over power and the country’s vast oil riches.

Already, in the wake of the killing, there have been calls for bin Salman’s uncle, King Salman, to move the Crown Prince out of the job.

“Internally, this is not playing well,” Shanahan says.

“Assuming the Crown Prince was responsible, he has made a significant number of enemies in the Kingdom, given the way he has cracked down on potential opponents and leapfrogged his way to power.

“He’s got enemies back at home and you can be pretty sure they are trying to delegitimise him.”

Meanwhile Turkey, whose own President Recep Erdogan has lately set his country up as a spoiler to the West and drawn closer to Saudi Arabia’s mortal enemy, Iran, has played a very canny diplomatic game since the murder.

“If you’re the government of a sovereign country, another government sending people in to kill someone on your soil is appalling”, points out Shanahan, who notes that “the accuracy and details of what they’re giving to the press (suggests) they had some way of knowing what happened minute by minute” — including, possibly, having bugged the consulate.

But while the killing has outraged much of the world, over the long run the Saudis are not likely to suffer much in the way of repercussions, according to Dr Isaac Kfir, director of national security at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute in Canberra.

Kfir believes the murder of Khashoggi was a military operation gone bad.

“They didn’t anticipate they were going to cock it up so badly,” he tells Saturday Extra, comparing it to the failed Israeli attempt to assassinate the head of Hamas in the 1990s.

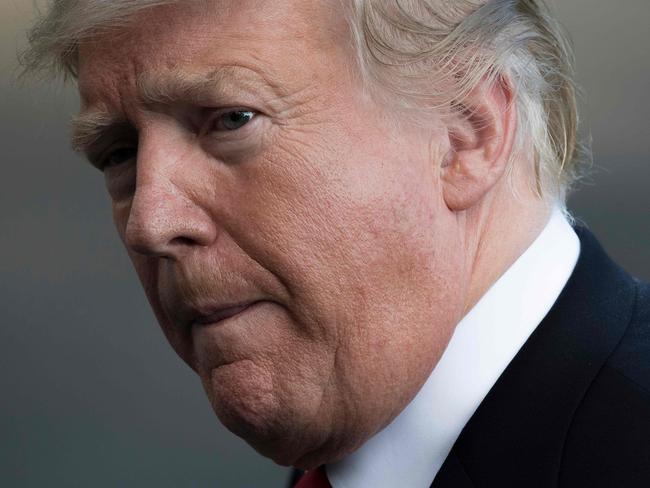

But, he also points out, with the Trump administration both seeing Iran as the greatest threat to peace and stability in the Middle East and counting on Riyadh’s help to advance the Israeli-Palestinian peace process, the likelihood that Saudi Arabia will suffer long-term blowback for the operation is low.

While much has been made of a $US100 billion arms deal between Saudi Arabia and the US, in truth, the stakes are far higher.

Because of Saudi Arabia’s strategic position, a collapse of the House of Saud would have the potential to effect not just control of the Persian (or Arabian, depending on who you’re talking to) Gulf with its vital oil flows, but also commerce through the Red Sea to the Mediterranean.

Interruption of these shipping lanes by a hostile power such as Iran or its proxies — the Tehran-backed Houthis launched attacks that temporarily suspended shipments of oil to Europe through the Red Sea as recently as July — would have devastating consequences for the price of oil and global economies, including Australia’s, more generally.

Others note that while the Saudis violated a laundry list of moral, legal and diplomatic principles in killing Khashoggi in such a brutal and brazen fashion, they are hardly alone.

Here the outrage over Khashoggi’s murder is likely being amplified by Donald Trump’s attempts to draw the US-Saudi alliance ever tighter, with some commentators somewhat bizarrely linking the US President as, at the very least, an accessory to the crime.

And as the history of the Middle East shows, no matter how nasty a regime might be, the possibility always exists that whatever comes next will be worse.