Three generations of women speak out about the ripple effect of men’s suicide

A mum, sister and daughter have bravely opened up about how a shock suicide in their family has affected their lives — urging men of all ages to seek help if they are struggling with their mental health.

NSW

Don't miss out on the headlines from NSW. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Nicola Cowlard doesn’t remember her dad, but there isn’t a day that goes by that she doesn’t think of him, mourning all the time she never got to spend with him.

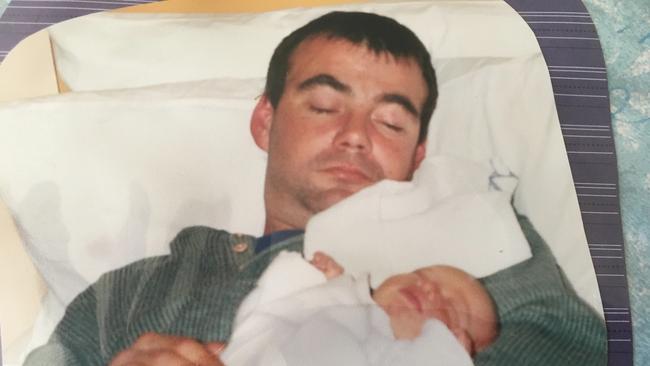

Her father Jonathen Cowlard took his own life when she was just two-years-old. His little girl was his “favourite person”, but his lifelong struggles with mental health became too much.

“It’s a bit bittersweet for me, learning about a stranger who was meant to be a big part of my life, and teach me things like playing basketball,” she said.

“I remember my formal and everyone was doing the daddy-daughter dance, I just started crying – it was the realisation that I missed out on having a father figure and how that has impacted every part of my life.”

Nicola, Jonathen’s mum Ryrie Bridges and his sister Jacqui Richardson are just some of the silent victim’s behind the men’s mental health crisis in Australia – with the three generations of women still grappling with Jonathen’s death 22 years on.

A world-first report by the Movember Men’s Health Institute, has found the leading cause of death for men aged 15 to 44 in Australia is suicide – with men three times more likely to take their own lives than women.

According to The Institute, informal caregivers – seven in 10 of whom are women – suffer worse physical and mental health, lost career opportunities and financial stress as a result of men’s suicide and other issues like drug and alcohol abuse.

Jonathen had struggled with depression and anxiety since he was a teenager – and eventually addiction became a coping mechanism.

His mother says she will “die sad” thinking about the pain her son felt, his sister often battles feelings of guilt, and his daughter has been hospitalised for her own mental health – with the ripple effect of Jonathen’s suicide still felt today.

“I often feel a lot of guilt that I survived and he didn’t,” Jacqui said.

“How did I get through life and he didn’t? How can we be the same? What is it about the genetic makeup that made it all so much more difficult for him?”.

For Ryrie – the grief comes in waves, and can hit at any moment.

“The thought of him (taking his own life) and the grief was so severe that it was very hard to really put your mind to work and other parts of your life,” Ryrie said.

“I might be somewhere that I love and suddenly that grief will hit me, and it’s a grief that my son didn’t think this world was worth living in, or he wasn’t able to live in it. It affects you forever, and I will die being very sad.”

For Nicola, her dad’s passing led to her own mental health struggles – but also influenced the career path she took, now working in the mental health space.

“If I could potentially influence someone to stay alive one extra day then I’ve made a difference,” she said.

“I want to show people that being vulnerable and speaking about how you feel is not something to be ashamed of, I want to give someone all the resources so they have the opportunity to get help, and not leave their children or their families behind.”

Jonathen’s mum and sister tried to get him appropriate help and support for many years – but found the stigma around men’s mental health prevented Jonathen from engaging.

In a letter Jonathen wrote to Ryrie and Jacqui before he died, he told them he was sorry but “I just can’t go on living like this” … and ended it apologising for being “weak”.

It’s that word that haunts them today – worrying about other young men who are depressed and battling suicidal ideation.

“The messaging in the community was ‘pull yourself together’, you’re a strong man you can’t cry,” Ryrie said.

“And we know that in some cases that’s still the reason people won’t come forward and we desperately need to change that.”

The report found that 63 per cent of men have faced harmful gender stereotypes in their interactions with the health system, such as the expectation that men should ‘tough it out’, while 34 per cent of men reported waiting more than a month to seek out help for their health.

Professor Simon Rice, Global Director of the Movember Institute of Men’s Health, said early intervention was key in improving men’s suicide statistics – and pushed for greater “gender-based” supports for teen boys and adult men.

“Every day, seven men in Australia lose their lives to suicide and the vast majority have been in contact with mental health services a year prior to their death,” he said.

“(But) we are missing critical opportunities for early intervention. It’s clear that the current approach is not working for men.”