Bruce Lee was a hot-headed, pot-smoking rebel whose legend has endured because he made the impossible seem possible.

His celebrity is entirely posthumous. He died at the age of 32, one month before the release of Enter The Dragon (1973) turned him into an international icon.

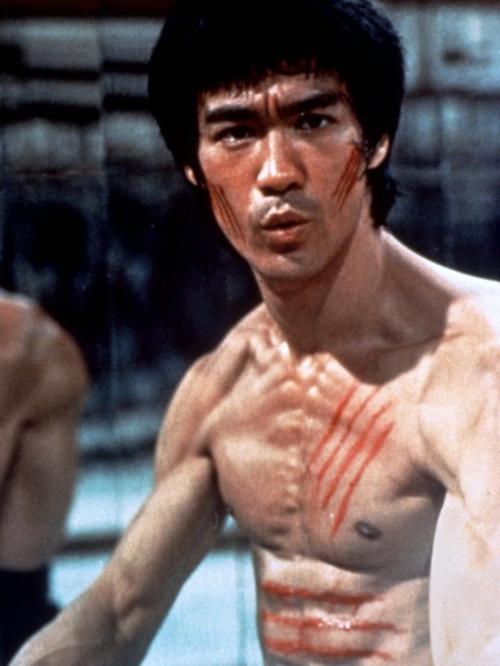

Two hours of watching Lee punch, kick and hack his way through dozens of bad guys

in a ballet of directed violence inspired millions of kids the world over to take up martial arts.

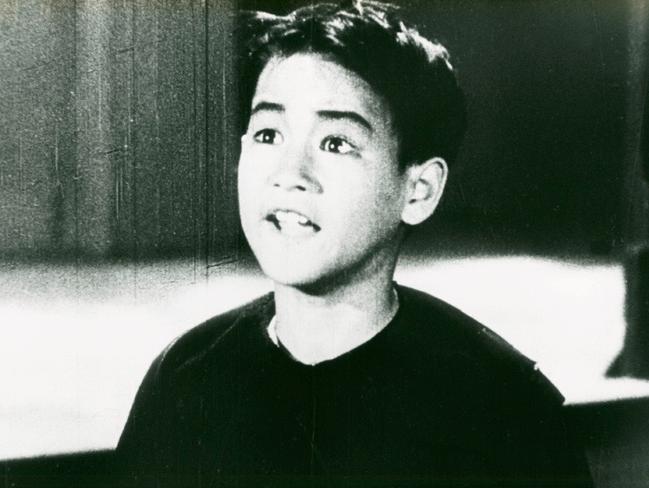

A terrible student who couldn’t sit still in class, his favourite extracurricular activity was fighting

In exchange, they worshipped him like a demigod, the patron saint of kung fu. Lee single-handedly introduced more Westerners to Asian culture than anyone since Marco Polo.

I know because I was one of them.

I first watched Enter The Dragon as a skinny, bullied 12-year-old in Topeka, Kansas.

I had never seen a kung fu movie before and had no idea who Bruce Lee was.

But as he jumped off the screen into my imagination, I wanted to be Bruce Lee.

Thirty years later as I began my research into the first authoritative biography of the martial-arts movie star, I wanted to understand him.

I discovered the many ways the man differed from the myth.

Lee’s eventful life nearly ended before it started. His father, a famous Chinese opera singer, and his wealthy Eurasian mother — half English, one-quarter Chinese, and one-quarter Dutch-Jewish — were touring America when Bruce was born in 1940.

A few months after his family returned to their native Hong Kong, the Japanese invaded. Among other horrors, a cholera outbreak ravaged the colony, almost claiming baby Bruce among its victims.

As a result of his near-fatal illness, he grew up frailer than other children, unable to walk without stumbling until he was four years old.

Short, skinny and near-sighted, Bruce grew up with a chip on his shoulder.

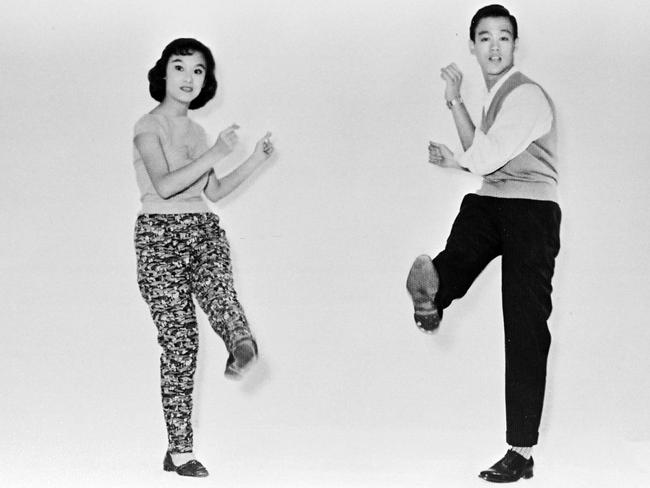

A terrible student who couldn’t sit still in class, his favourite extracurricular activity was fighting.

As a teenager he took up kung fu not for self-defence but to become a better street brawler. He was hypercompetitive and hated to lose.

He eventually picked so many fights, the police warned his mother that if he didn’t stop they would have to throw him in jail.

In 1959, his parents, at their wit’s end, decided to ship him off to his country of birth. America was Bruce Lee’s reform school.

The shock of being banished had a transformative effect. He knuckled down on his studies, gained admission to the University of Washington and opened his first martial arts school. Unlike more insular and chauvinistic Chinese-American instructors of that era, Lee wanted to share kung fu with everyone.

I told him there was no way he could be a big star. He was a Chinese in a white-man’s world

His first student was African-American.

“If he felt you were sincere, Bruce taught you,” recalls Taky Kimura, one of his Japanese-American students.

“He didn’t care what race you were.”

Lee’s career goal was to become to kung fu what Ray Kroc was to McDonald’s, franchising dojos along the West Coast.

To gain more students, Bruce often took his act on the road, like his father before him, treading the boards in what was the equivalent of a one-man martial arts show.

It was during a performance at a 1964 karate tournament that Lee was discovered by William Dozier, who cast him in the role of Kato, the lethal Asian sidekick to the Green Hornet.

Despite Lee’s magnetic martial-arts skills, The Green Hornet, which lacked the campy wit of Dozier’s hit companion series Batman, failed to find an audience and limped along for one season before being cancelled. For the next five years Lee struggled to find worthy acting roles to support his family and, in desperation, discovered a new source of income.

He became the kung fu instructor to Hollywood’s elite, counting as his private students James Coburn, Roman Polanski, Oscar-winning screenwriter Stirling Silliphant and box-office king Steve McQueen.

Fuelled by years of rejection, Lee leapt off the screen, pulsating with a volatile power that was all his own

It was McQueen who became Lee’s role model and mentor in swinging ’60s Hollywood. He turned Bruce on to marijuana.

They even competed over the same woman, the actor Sharon Farrell. (She eventually dumped Lee for McQueen because Steve was a box-office champion and Bruce “didn’t have a pot to pee in”.)

“Bruce vowed, ‘Some day, I’m going to be a bigger star than Steve McQueen,’ ” recalls Silliphant.

“I told him there was no way. He was a Chinese in a white-man’s world. Then he went out and did it.”

Unbeknown to Lee, The Green Hornet was sold in syndication in Hong Kong, where it became known as The Kato Show.

During a quick trip back in 1970 with his five-year-old son Brandon, Lee was stunned at the reception.

He may have felt like a failure in Hollywood, but in Hong Kong he was the hometown boy made good.

Hong Kong movie producers started making offers.

Following the example of Clint Eastwood who, unable to make the leap from American TV to film, had gone to Italy to make several spaghetti westerns that turned him into a bankable star, Lee signed a two-picture deal with Raymond Chow and his upstart Golden Harvest studio for $7500 a film.

If Lee could not climb Hollywood’s mountain, he would make the mountain come to him.

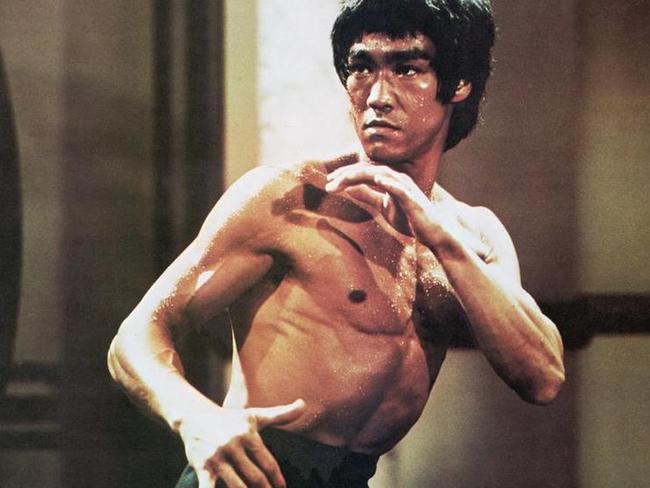

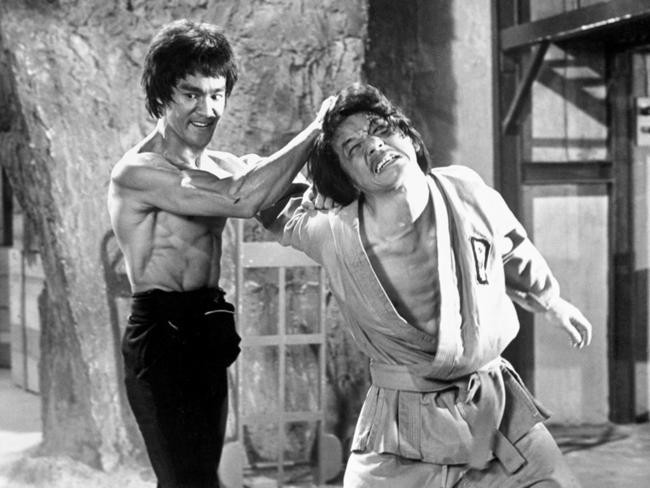

In his first Golden Harvest movie, The Big Boss, Lee looked transformed.

Gone was the pleasant manservant Kato.

Fuelled by years of rejection, Lee leapt off the screen, pulsating with a volatile power that was all his own.

Audiences in Hong Kong and across South-East Asia loved their new Chinese superhero.

The Big Boss broke all Hong Kong box-office records.

His second Golden Harvest film, Fist Of Fury, shattered the record of The Big Boss.

His third film, Way Of The Dragon, which he wrote, directed, produced and starred in, broke both of those records. Lee was a juggernaut.

From across the Pacific, Hollywood saw all the money and came calling — just as Lee had predicted.

Producer Fred Weintraub struck a deal with Raymond Chow for the first ever Hollywood-Hong Kong co-production.

He died in the apartment of his mistress - sultry Taiwanese actress Betty Ting Pei

An 85-page screenplay was banged out about three heroes (one white, one black and one Asian) who enter evil Han’s martial-arts tournament and end his drug-dealing, slave-trading ways.

Hollywood still didn’t believe an Asian actor could carry a movie on his own.

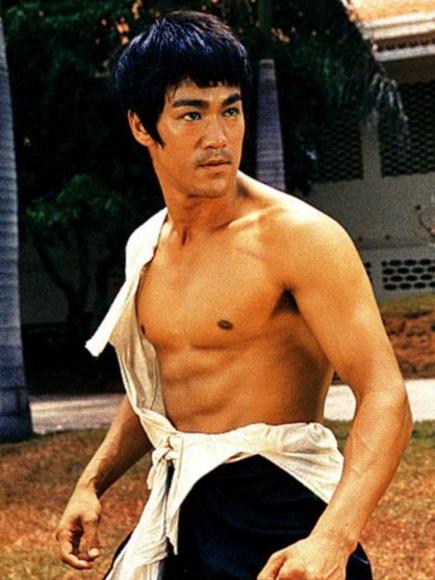

Terrified that Warner Bros would recut the movie to make the white character (played by John Saxon) the star, Lee fought on screen and off to stamp his personality onto every frame. The result was a performance so intense he seems to vibrate off the screen.

The stress of filming Enter The Dragon drained Lee physically and mentally.

He was having trouble sleeping and lost 9kg on a body that already had minimal body fat.

Instead of taking a much- needed vacation, he threw himself into his next project, Game Of Death.

Lee was terrified that if he didn’t seize the moment, the chance to become the biggest star in the world — bigger than Steve McQueen! — might slip away from him.

On July 20, 1973, he went over to the apartment of Betty Ting Pei, a sultry Taiwanese actor, for a “nooner”.

Later in the afternoon, Raymond Chow came over to pick them up to meet George Lazenby, the Australian actor who played James Bond in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1969), for dinner. Lee wanted to cast Lazenby in Game Of Death.

It was a scorching day — with a temperature of 32 degrees and humidity of 84 per cent.

“Bruce wasn’t feeling very well,” Chow told me in an exclusive interview. “I wasn’t feeling very well either. I think we had some water, and then he was acting.”

In his bubbling enthusiasm over Game Of Death, he jumped up and performed scene after scene.

“He was always very active,” Chow said. “In telling the story, he acted out the whole thing. So that probably made him a little tired and thirsty.

“After a few sips he seemed to be a little dizzy.”

Lee complained of a headache and told Chow to go on without him. He went to lie down in his mistress’s bedroom and never got back up again.

The scandal surrounding the circumstances of Lee’s untimely death and the attempts to cover it up (Chow initially told the Hong Kong press that Lee collapsed at home with his wife Linda) fuelled countless conspiracy theories, ranging from the ridiculous (poisoned by Japanese ninjas or the Chinese triads) to the sublime (killed by an ancient curse or bad feng shui).

In speaking to numerous forensic and medical experts, my conclusion is Lee most likely died from heat stroke.

A few months before his death, he had undergone elective surgery to have the sweat glands from his armpits removed, because he didn’t like how his dank pits looked on screen.

The end of Lee’s life was the beginning of his legend.

Dying at the peak of his powers, Bruce Lee achieved immortality.

He had set for himself the overwhelming task of becoming the first Chinese actor to ever star in a Hollywood movie and against all odds he succeeded — proving that impossible dreams are possible if you are willing to pay the ultimate price.

Matthew Polly is a best-selling author and student of kung fu.

Bruce Lee: A Life by Matthew Polly (Simon & Schuster, $35) is available now.

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout