THEY are a dwindling band of living treasures, but Australia’s remaining Holocaust survivors still have a key role to play in educating our youth.

As studying the Holocaust is rolled out in both years 11 and 12 in high school in 2018, they represent a trove of firsthand experience of the best and worst of humanity.

Across the country about 7000 survivors remain of the 27000 who immigrated here after World War II. In Sydney there are about 3000, of whom 30 regularly speak of their experiences through talks organised by the Sydney Jewish Museum

We never talked about the Holocaust for many many years ... no one was interested and we were not ready

Today, some of those survivors will gather at the museum in Darlinghurst to commemorate the liberation of Auschwitz and the UN Holocaust Memorial Day.

When you speak to many of the survivors who volunteer their time at the museum a sense of urgency is clear. Over the years, the number of adult survivors of the war has diminished and their testimonies are a valuable resource that will not be around forever.

To address this, the museum is expanding to incorporate a new Holocaust and Human rights area and exhibition that will run education programs and will be launched in February.

Traumatised by the Holocaust, survivors like 90-year-old Yvonne Engelman were initially hesitant to share their stories.

“We never talked about the Holocaust for many many years [because] no one was interested and we were not ready,” Ms Engelman said.

The survivors now share their stories daily in an attempt to prevent history repeating itself.

The CEO of the Sydney Jewish museum said: “Survivor testimony provides a critical first hand and personal account of the horrors of the Holocaust and regularly leaves a deep and lasting impact on the audience.

“We are extremely fortunate to still have more than 30 living witnesses sharing their stories with school students and other visitors.

“The Museum has helped many survivors publish their stories and we are continuously recording their testimonies to cater for the time when there are no longer survivors.

“We have also created a ‘Voices App’ which allows visitors to listen to the stories of survivors as they walk through Museum.”

The museum which opened its doors for the first time on November 18, 1992 has a longer connection to Sydney’s Jewish community. The building was previously a Maccabean Hall which operated as a community centre used for Jewish weddings, bar mitzvahs and functions.

Today, however, it is best known for the direct teaching of the Holocaust legacy, and has become almost a surrogate community centre for survivors of Hitler’s attempted genocide of European Jews.

There are few more powerful stories to hear than those of these remarkable people. Today we share some of them here and, at dailytelegraph.com.au and iTunes, in a series of podcasts.

FOUR STORIES FROM CHILD SURVIVORS OF THE HOLOCAUST

YVONNE

Yvonne Engelman is petite and warm, with unmissable rosy cheeks.

“Can you see how red I am, my cheeks? Not rouge,” the 91-year-old says in her Czech accent.

Behind her pink cheeks, though, her story isn’t rosy in the slightest.

Born in Dovhe, Czechoslovakia, Engelman ’s earliest recollection of when things started changing was when her schoolmates behaved as though she was invisible. It’s something she can’t forget, even today in this new life.

A second memory that continues to haunt her is of her beloved father with his front teeth knocked out by the Nazis.

“(My father’s) only crime was that he was a Jew,” she says. He and her mother were later murdered. Rejected by Dr Josef Mengele at Auschwitz, their lives were deemed unworthy. Despite the SS guards taking her mother away, 15-year-old Engelman continued to have hope.

“They used to give us a really thin slice of bread (and) I always kept half in case I met my mother.”

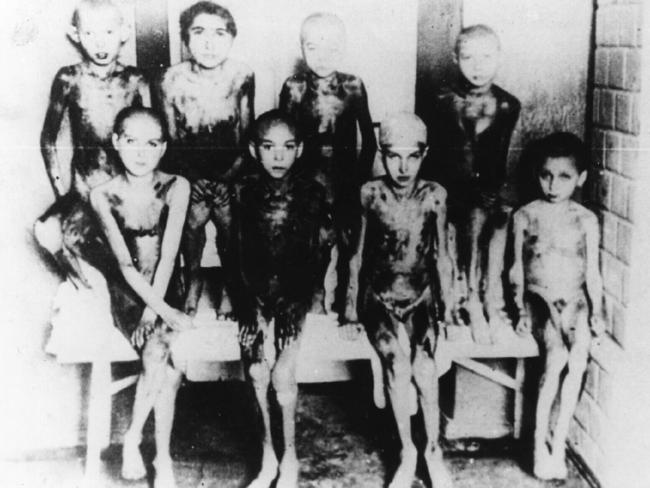

Surrounded by electric barbed wire and ferocious dogs, she remembers her younger self not as a beautiful young girl but as bloated, hungry and frightened. It’s hard to reconcile this image with the healthy, dynamic woman she is today.

Estimates suggest 960,000 Jews were victims of the Auschwitz concentration camp complex, including the killing facility at Auschwitz-Birkenau. Engelman recalls the haunting sound of children coughing and screaming until the gas silenced their voices.

She was on the cusp of being one of them but a technical issue with the gas chambers spared her life. It was this narrow escape that allowed her to fulfil the promise she made to her father before they left their home.

“I don’t know where we are going but I’m sure it’s not a holiday,” he said.

“You have to promise me one thing — that you will survive.”

She did, against the odds, and lives to retell her story.

Liberated on May 8, 1945, by the Russian Army, Engelman was sponsored by a Jewish organisation that sent her to Australia. Penniless and unable to speak English, she still found the country heaven. “Just to be able to walk on the street and nobody abuse you — that was so precious to us.”

Engelman began working in a factory for three pounds a week and met her husband, a cabinet maker from Czechoslovakia, who had also survived the war. Their wedding day was a humble celebration but it brings a smile to her face as she recalls wearing a borrowed wedding dress and a ring made of the thinnest gold.

“Possessions have never played a big part in my life,” she says.

Today, Engelman is proud to call Australia home. It’s where she laid down her roots with her three children, David, Shirley and Jeffrey, and several grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

“We never talked about the Holocaust for many many years (because) no one was interested and we were not ready.”

This has changed.

For the past 25 years, Engelman has been visiting the Sydney Jewish Museum every Tuesday to tell her story to eager young students. Despite the nightmares this brings on, Engelman sees it as her obligation to those who didn’t make it as far.

Her survival sometimes seems unbelievable to her own ears. “Sometimes I think ‘Did I really survive that?’”

PAUL

Paul Drexler had only one question for his mother when she returned home every day from her trip to Bratislava in Slovakia: “Where’s Daddy?”

His question was answered six weeks later. His father, Eugen, had been murdered on May 3, 1945, five days before the end of World War II. Drexler is one of about 7000 Holocaust survivors in Australia today. Like many, he was a child when one of history’s cruellest chapters unfolded.

Oblivious to the politics occurring around him, all that four-year-old Drexler knew was that 60,000 Slovakian Jews had been sent to their deaths. His family was one of the 13,000 exceptions granted to Jews who were crucial to the economy.

Drexler knows that if it wasn’t for this “tremendous luck”, he wouldn’t be here today. But being exempt didn’t mean the family didn’t face their own share of horrors. The three of them were taken to the police station and it is here that Drexler recalls losing his childhood.

“I witnessed my parents being tortured. Their backs were black, blue and bloody,” he says.

In this terrifying memory, Drexler remembers clinging for comfort to two cashmere blankets his father made. One is displayed in the Sydney Jewish Museum, where he is a regular visitor. It remains a constant reminder of the horrors he survived and the effort his mother made to protect him.

In 1944, separated from his father, Drexler and his mother made a harrowing journey to Auschwitz.

It was December 20 and the Nazis were under strict orders to eliminate all evidence of the gas chambers for the approaching Soviet Army. The arriving Jewish prisoners were unwanted. “This is the second time I was really lucky, because there’s no way I would have survived if Auschwitz was still in operation.”

The stories Drexler shares of his time in a boys’ home at Theresienstadt are a testament to his mother’s fight to save him.

She eventually succeeded in convincing the authorities to allow Drexler to live with her, after which she began smuggling scraps of food back to her young son, who was unable to survive on food given to the prisoners.

“I had a childhood which could have ended very early had I not been lucky and had my mother not looked after me,” he says.

The mother and son remained in Theresienstadt until liberation. Drexler recalls seeing rows of skeleton-like evacuees from slave-labour camps coming off the trains. But a more horrific view was looking at what remained on the train — prisoners who didn’t make it to the end of the journey.

A month later, Drexler and his mother were liberated. It’s the only day of the war that he recalls being sunny. Every other day looked overcast. “We’ll be going home soon,” his mother told him.

Today home is Sydney, where Drexler and his traumatised mother arrived on January 15, 1948. Every subsequent year they ate ice-cream on the anniversary to celebrate their survival.

Drexler went on to become an accountant, marry and have two daughters and three grandchildren. Despite living through one of the worst genocides in history, he believes he has been “exceptionally lucky”.

JACK

IT’S difficult for Jack Meister to recall his exact age at the start of World War II. “I was about 10 and a half; I can’t remember,” he says.

Between 1940 and 1945, bar mitzvahs and birthdays were a distant memory for the now 89-year-old and it’s hard to recall the exact numbers.

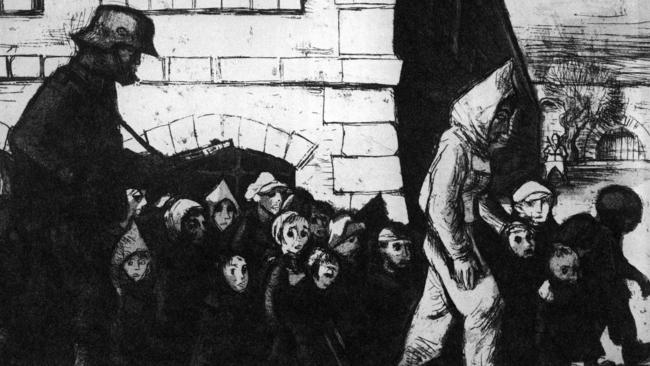

Other things, though, he remembers in vivid detail even after all these years. He recalls the moment he calls “the worst thing in my life”: when Jewish families were rounded up in his hometown of Kielce, Poland, and taken to the ghettos. You couldn’t go in or out unless you had a work permit.

Meister was young and healthy enough to be permitted to work, a luxury in those circumstances.

But things got worse in 1942, when the ghetto was shut down. Families were separated and Meister was sent to Auschwitz.

“They put us in a wagon and we had to travel to Auschwitz,” he says. “You didn’t have nothing to eat. You travel all day, all night.”

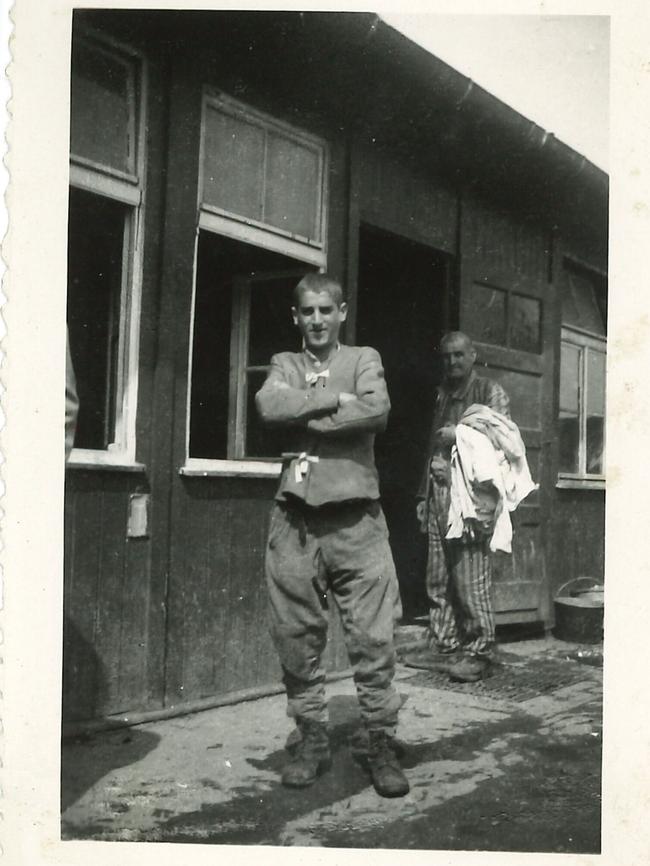

It was in Auschwitz that he acquired the tattoo on his forearm: B488. Marked with this new identity, Meister was sent to the Buna concentration camp.

“Buna was a camp where they looked after the workers; we had no trouble with the SS,” he recalls. “We went to work in the morning, music was playing.”

Although Meister believes Buna was better than the other camps, it was no paradise. They were still prisoners with restricted rights and minimal freedom.

He recalls one incident where a man was hanged for attempting to escape. When they returned from work that day, the usual music didn’t play. It was a gesture Meister still can’t understand.

“They killed so many people without worrying about it but they hang somebody and the music didn’t play,” he says.

The camp was liberated by American troops in April 1945, after which the Red Cross took him to Switzerland. He then came to Australia.

“I got married here,” he says, looking around the Sydney Jewish Museum, where he volunteers. Meister and his wife stayed together for 65 years and had a daughter and two grandchildren.

“I’m happy ... my life started very bad but it picks up when I came here,” he reflects.

OLGA

Olga Horak remembers two very different versions of Czechoslovakia.

The first is what she describes as “the only true democracy in central Europe” before World War II and where she enjoyed “wonderful human rights”.

The second is a world where the Nuremberg laws were accepted and where as a result, she wasn’t allowed to go to school, have non-Jewish friends, sit on benches in parks or go out after dark.

The now 90-year-old Holocaust survivor recalls the moment Jewish children were “collected” from their homes and sent to Auschwitz. One of them was her 16-year-old sister Judith, who was removed by guards in 1942. Horak never saw her again.

Traumatised and heartbroken from losing their daughter, Horak’s parents took refuge in the spare apartment of a neighbour, who offered to help.

Two weeks later, the same neighbour brought Nazi guards to the apartment and denounced them. “The people who turned a blind eye were just as criminal as the criminals themselves,” Horak says.

She and her family were sent to Auschwitz, where her father and grandmother were taken straight to the gas chambers.

Horak and her mother survived and were stripped, shaven, numbered and given rags to wear. She sums up her new reality in one sentence: “It was easier to die than to live.”

Horak and her mother survived the death march to Bergen-Belsen and lived to see the camp’s liberation in April 1945. She recalls removing the rags she was wearing and the frozen skin peeling away underneath.

As they waited in line to register themselves for ID cards, her mother lost her fight and collapsed.

Orphaned and carrying the fresh scars of the Holocaust, Horak met her husband John, with whom she moved to Australia in September 1949. The two refugees established a manufacturing business and went on to have two children.

Today, Horak is one of the survivors who volunteer at the Sydney Jewish Museum in an effort to keep these stories alive.

“I don’t live in the past; the past lives in me,” she says.

As told to Angira Bharadwaj

Podcasts by Georgia Hing

‘Scary invasion of privacy’: Meta’s teen tactics slammed

A young Sydney woman has slammed Facebook’s “scary’ marketing techniques, after a whistleblower from the social media giant laid bare how low it went to boost advertising revenue.

Energy experts unpack fiery election face-off on power prices

This article is part of a CONTENT PARTNERSHIP with Sky News, Australian Energy Producers, Clean Energy Council and Minerals Council of Australia.