Sydney engineer Warwick Holmes played a vital role in landing the Philae probe onto a comet

SYDNEY avionics engineer Warwick Holmes was starstruck as he watched the Rosetta spacecraft — which he had helped build — land a robot on a comet.

NSW

Don't miss out on the headlines from NSW. Followed categories will be added to My News.

HE watched as an eight-year-old when Neil Armstrong became the first man to walk on the moon.

Yesterday Sydney avionics engineer Warwick Holmes was no less starstruck as he watched the Rosetta spacecraft — which he had helped build — land a robot on a speeding comet after a 6.4 billion kilometre, 10-year trip through space.

“We’ve turned science fiction into science fact today,” Mr Holmes, 53, said yesterday.

“It’s been one of the most incredible results ever in space exploration history.”

ROSETTA’S PROBE MAKES HISTORIC COMET LANDING

Mr Holmes, who began his space industry career working for free just to gain experience, watched from the European Space Agency’s headquarters in Darmstadt, Germany, as history was made.

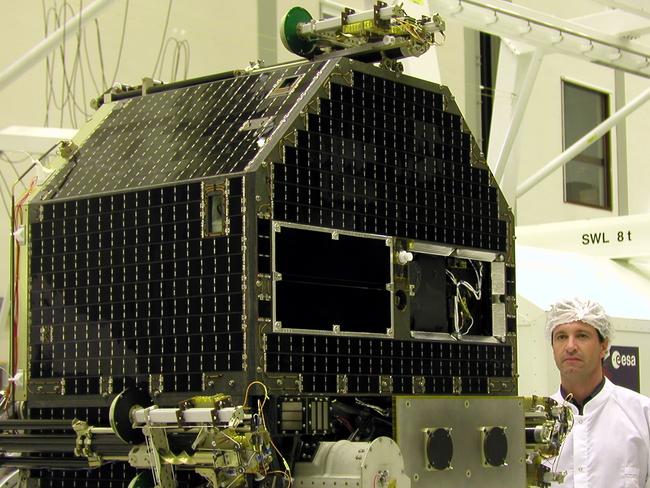

He spent almost five years helping build and test the spacecraft, which has already begun sending back pictures from 511 million kilometres away.

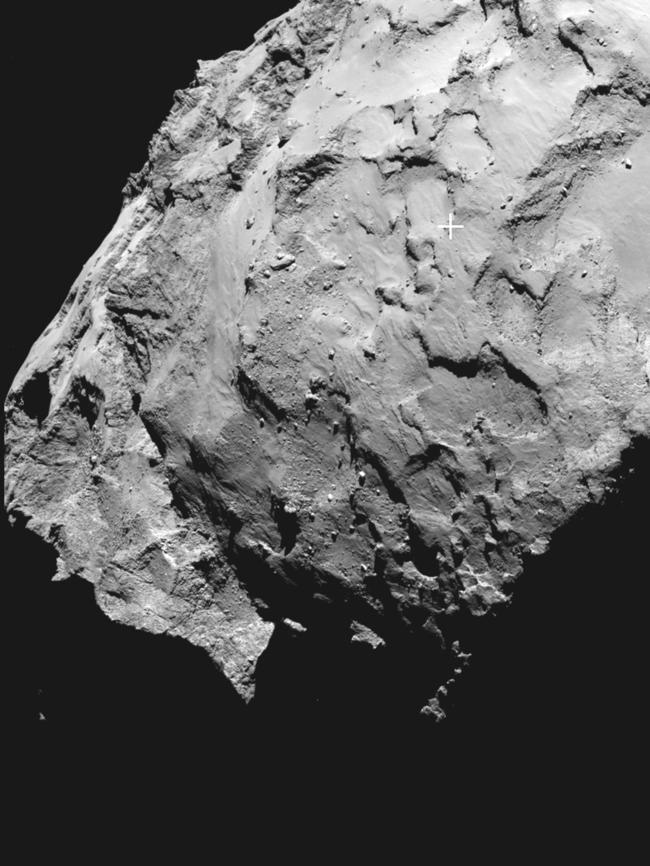

Mr Holmes said the data collection would give scientists the chance to prove how water got to Earth at a time when our planet was just a red hot ball of molten rock.

“After it cooled down something happened, comet material came down and hit the earth again and they believe this has carried the water that has made the oceans,” the former Sydney University student said.

“We’ll be able to prove definitively that the molecules on the surface are responsible for the formation of life on Earth.”

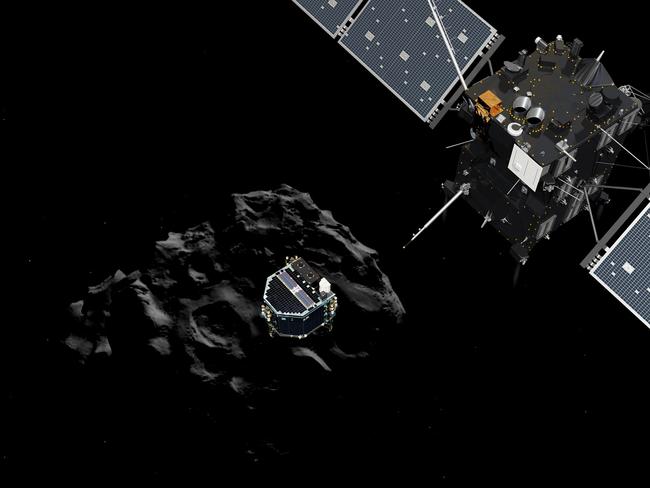

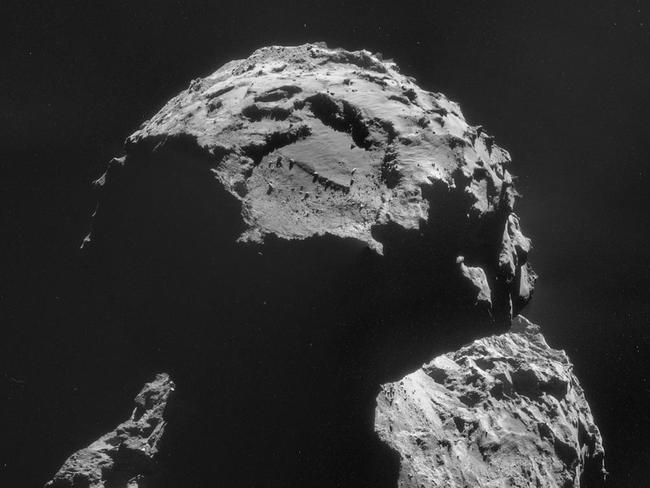

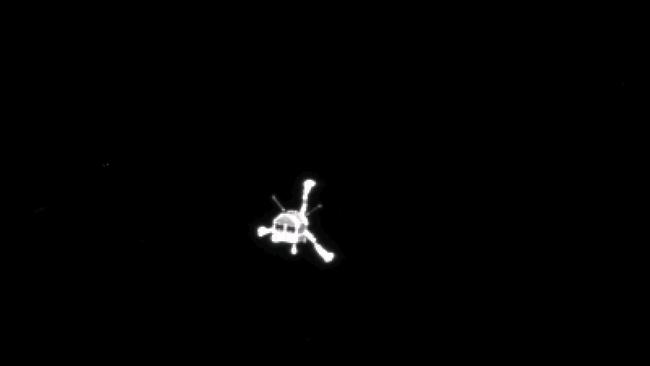

As Rosetta landed its washing-machine sized robot, Philae, on the icy surface of comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko after a seven-hour descent, at “mission control” in Germany there were cheers — and tears of relief — from the team of experts behind it.

“This is a big step for human civilisation,” the agency’s director general Jean-Jacques Dordain said as scientists, guests and VIPs applauded.

“With Rosetta we are opening a door to the origin of planet Earth and fostering a better understanding of our future. ESA and its Rosetta mission partners have achieved something extraordinary.”

In other parallels with the first moon landing in 1969 when the Parkes telescope transmitted the Apollo 11 signals to the waiting world, Australia played a pivotal role in the Rosetta mission.

This time signals from Rosetta were picked up via the ESA Deep Space Ground Antenna in New Norcia, 150km north of Perth, and the Canberra Deep Space Communication Complex at Tidbinbilla, during the spacecraft’s 10-year mission.

SCROLL DOWN FOR MORE

At Tidbinbilla, self-described “space cadet” Glen Nagle said he cried tears of joy.

“It was the combination of the 10-year voyage to do something that was incredibly daring and had never been done before and the tension that was building up at the ESA centre in Germany,” Mr Nagle, spokesman for the tracking station managed by CSIRO as part of NASA’s Deep Space Network, said yesterday.

Like Mr Holmes, he watched the moon landing as an eight-year-old but never thought he would be involved in another space milestone.

“A lot of people at mission control centre were relating this with the first man to step onto the moon,” he said.

Rosetta was launched on March 2, 2004, and travelled a circuitous 6.4bn kilometres through the Solar System — using the gravity of Earth and Mars as a slingshot to pick up speed — before catching up with the comet on August 6.

The most complex mission ever attempted cost $2 billion and was put together by many countries. There were a couple of hiccups at the end with failures by the landing craft’s thrusters and harpoons which were designed to help it stick to the comet.

When Philae’s batteries run out by the weekend, it is hoped solar power will kick in for another five months.

STARMAN LOST IN SPACE THE MOMENT HE SAW ARMSTRONG’S MOON WALK

Warren Gibbs

WARWICK Holmes is a self-confessed space junkie who grew up in Sydney believing the sky’s the limit.

“I was a pretty ordinary student, who had a big dream, an obsession, of being part of the space revolution,” Mr Holmes said last night from the European Space Agency in Germany.

His love affair began when as a grade two student he watched grainy black and white footage of Neil Armstrong’s 1969 historic moon walk.

While other kids around him quickly lost interest, eight-year-old Holmes couldn’t keep his eyes off the TV. “I was totally mesmerised. There were a million questions going through my mind about the mission, but no-one to answer them,” he said.

But rather than follow in the footsteps of Armstrong, Mr Holmes said his interest was in the spacecraft that got him there.

From that moment, space consumed Mr Holmes, who attended Kings College in Paramatta, before studying electrical and science engineering at Sydney University.

With no space program in Australia, the then 24 year old decided to reach for the stars, applying for a job at British Aerospace. “I pleaded with them to give me a job, saying I would gladly work for free,” he said. He was given the job of repairing a satellite with mechanical problems called Olympus. “I worked seven days a week, 12 to 14 hours a day, but I managed to get it fixed.”

Mr Holmes has an apartment in Sydney and returns home whenever he gets the chance.

LOOK WHO’S TALKING: PHILAE SENDS FIRST HAPPY SNAP

SCIENTISTS have re-established communication with the Philae space probe.

The lander was “stable” despite concerns after a harpoon, which was meant to tether it to the surface of the 4km-wide comet, failed to deploy.

Rosetta project scientist Dr Matt Taylor said the European Space Agency was receiving a good signal and receiving science data.

“Now we are busy analysing what it all means and really trying to find out where the lander actually is on the surface,” he said. Philae landed in a soft area on the 67P/Churyumov-

Gerasimenko comet and dipped around 4cm before bouncing back up when its harpoon failed to fire.

It went straight back up for two hours and drifted out into space before descending to the surface. It bounced again for a few minutes before settling in what Taylor described as “three landings for the price of one”.

“The descent was due on to a particular point on the surface of the comet. The bounce would have made it go up and then the comet’s rotating underneath,” Dr Taylor said.

“So we know, if we are looking at an image, that most likely the lander is somewhere on the right and now we are trying to refine that to really start focusing on the orbiter images to see where it is.”