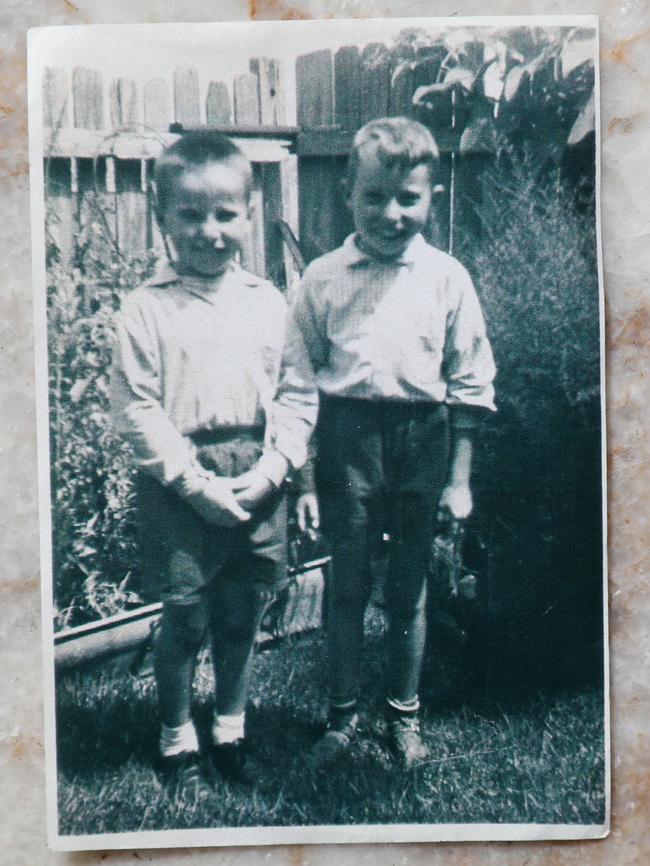

The black-and-white photographs, carefully preserved throughout a lifetime of secret trauma, are possibly the most heartbreaking thing of all.

In these photographs they are innocent, full of wonder and with all the potential in the world.

Smiling on a sunny day, with the inevitable paling fence behind them, they seem to know nothing of evil or pain.

It was very violent, evil, horrific. We got raped, we were drugged. I remember everything clearly and it’s never left me.

But evil and pain would soon come to these children. In institutions such as orphanages, churches and schools, adults charged with safeguarding and nurturing children were to exploit their vulnerability, again and again.

Instead of receiving love and comfort, the children would suffer terrible sexual abuse.

They would be left with acute mental anguish and in some cases waited many decades before they shared their horrific experiences with another living soul. They would feel tainted and unworthy, their confidence destroyed.

But sharing can bring healing, and many people who told their stories to the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse have discovered there is light in the darkness.

Established in 2012 by former prime minister Julia Gillard, the royal commission handed down its report last year.

In response to that report, according to NSW Attorney-General Mark Speakman this week, the NSW Parliament recently passed a child protection package including new offences for failing to report or protect against child abuse.

The legislation also requires courts to deliver sentences “to reflect what we know now about the lifelong trauma that child sexual abuse causes”.

The new legislation requires courts to disregard an offender’s previous good behaviour in historical offences where the person���s high reputation actually facilitated their offending.

The federal government’s National Redress Scheme, announced last week, allows victims of institutional child abuse to apply for counselling, for financial redress of up to $150,000 and for a formal apology from the institution where they were abused.

Thousands of victims told their stories at the royal commission and, traumatic though it was for many of them to revisit their experiences, it often brought enormous relief.

For Patricia Charter, 80, just meeting one of the commissioners was a comfort.

“He gave us the feeling he would be relentless in pursuing the truth,” Charter says.

Today, she can’t believe she bottled up her stories for almost 60 years.

“Julia Gillard, thank you,” she says.

Wayne Iles says giving evidence was “like stirring mud in clear water”, but it gave him relief.

“After that I went down to the Botanical Gardens just to calm down a bit. I wasn’t angry or upset,” Iles says. “I’ve always been a strong person, as much as I can. But now I’ve got closer to that inner child.”

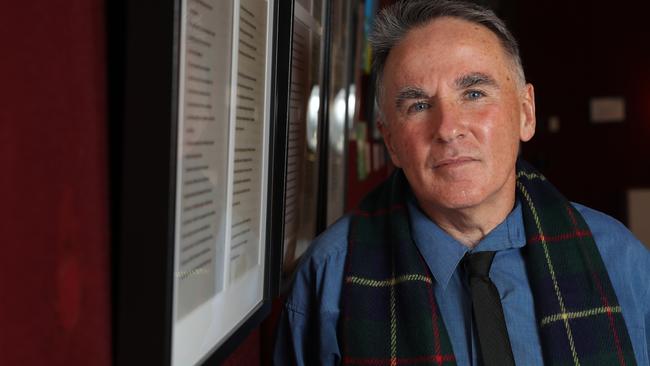

Damian Koch has done it tough over the years. He has even had to move houses suddenly, without telling his wife or children why. This occurred when one of the perpetrators of his childhood abuse rang him up, and asked whether he had children.

Koch has put on nearly 8kg since testifying. “I was like hell on a stick … now I’m feeling good,” he says. “I’m sleeping six and sometimes eight hours a night, and I’ve never done that.”

Supporting Charter, Iles and Koch through their experience as witnesses before the royal commission was a non-profit relationship agency called Interrelate.

Interrelate chief executive Patricia Occelli says the royal commission was the first opportunity many people had “to actually have a voice, to actually express what had occurred to them, to have somebody truly listen and acknowledge the pain and suffering that they’ve had”.

Art and writing, often as part of therapy sessions, also helped survivors.

This week, an exhibition featuring a range of these works was opened by Attorney-General Mark Speakman at NSW Parliament House.

Entitled Journeys Of Hope, it includes the work of 24 survivors including Charter, Iles and Koch.

They told Saturday Extra their stories. In the only photograph that Charter has of her early childhood, she’s the cheeky one on the left. Older sister Kathleen, who would fare worse in life, is on the right.

The girls were aged four and seven when their mother woke them late one night and walked them through the dark to the nearby orphanage. Winter was coming in chilly Goulburn where they lived.

“I think my mother must have rung (the orphanage) because when she banged on the great big door it was only minutes before a nun opened it,” Charter says.

“She just pushed us inside, the nun shut the door and my mother disappeared. So there we were, the two of us.”

Charter’s mother was not coping. Her husband was away at the war and she resented having to raise five children without him.

Years later it turned out she had bipolar disorder. But none of that was evident to the four-year-old who soon found orphanage life to be horrific.

“The nuns would say, ‘Your mother doesn’t want you, we’ve got to put up with you, just behave yourself or else,’ ” Charter says.

“And it was mostly ‘or else’. Not that we didn’t behave. They didn’t need an excuse to abuse you.”

On weekends the orphanage children would be dressed up for events, their clothes covering their bruises.

In chapel on Sundays, the sisters’ mother would attend the service. But the sisters, sitting on pews with the other orphanage kids, were strictly forbidden from even looking at her.

“I’m sad to say I couldn’t bear not looking at my mother,” Charter says. “I’d be trying to get my little eyes to bore into her back saying ‘Mummy, take us home’, without speaking or moving because we weren’t allowed to in the church.

“Every time after mass we’d get a belting. They seemed to know everything that was in your brain.

“I think most of us walked around not wanting to see anything, wanting to be invisible.”

Just before Charter turned eight, her father removed his two daughters from the orphanage. But she was then enrolled in a local Catholic school where she experienced more cruelty.

Her knuckles were “bashed” so that she could not play the piano, which she loved.

Her sister Kathleen, meanwhile, had become a risk-taker.

“Kath started to break down after her first child at 20, then she subsequently had so many mental breakdowns and died at 39,” Charter says.

“She obviously had a much worse experience of sexual abuse than I did, which is so horrifying.”

The sisters never spoke to each other about their abuse.

As an adult Charter worked as a domestic violence counsellor.

“I’ve got at home a little pile of beautiful cards from my clients when I left my job at 74 … saying, ‘without you, Trish, I couldn’t have survived,’ ” she says.

Wayne Iles endured a terrible childhood. He was abused in institutional care as well as at home by his stepfather. But he finally found peace in painting.

Among his works in Journeys Of Hope is a beautiful picture of turtles.

He also wrote My Grandfather’s Magic Green Hammock, a short story recalling the happiest days of his childhood at his grandparents’ Jannali home.

Iles’ childhood was so badly marred by sexual abuse that he attempted to take his own life at the age of nine.

“It was more of a cry for help,” Iles says. “When I took the overdose — it was more than a dream — I was holding Jesus’ hand and I felt the love.

“It was the most peaceful thing you could feel … It helped me to where I am now.”

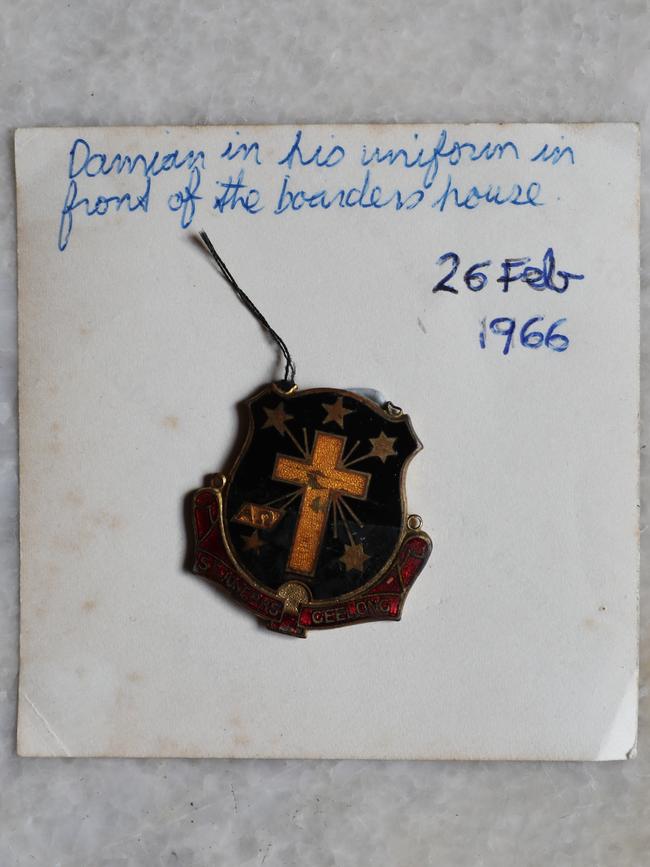

The largest work on view in Journeys Of Hope is a vibrantly coloured painting by Damian Koch, who was sexually abused while attending a prestige boarding school in Victoria in the 1960s.

Koch’s father was a wealthy Swiss engineer who travelled widely. Aged nine, Koch was enrolled in the boarding school.

In a picture dated February 26, 1966, he is neatly uniformed and smiling.

“It was very violent, evil, horrific,” Koch says of the school. “We got raped, we were drugged. I remember everything clearly and it’s never left me.”

Koch kept his ordeal secret for decades. But he found sanctuary in painting.

“I call it Damian’s World. I don’t have to think about anybody or what happened to me. I turn the phone off.

“I don’t have a computer or television, because it’s all too confusing,” Koch says.

He says his burden was eased when he gave evidence to the royal commission and when two of his abusers were jailed.

But one thing still bothers him — the little boy with “fuzzy hair” whose body he saw being loaded into a mortuary car at the boarding school.

Koch said his blanket was snatched away and thrown over the child’s body on a stretcher. When it was returned, the blanket reeked of death.

“It’s nearly a clean slate, except for that boy,” Koch says.

“Somebody else must say, ‘Oh yeah, I remember.’ ”

See Journeys Of Hope in the Fountain Court of NSW Parliament House, Monday to Friday, free, until August 2.

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout