Students demand realistic sex education: ‘I was taught self defence before consent’

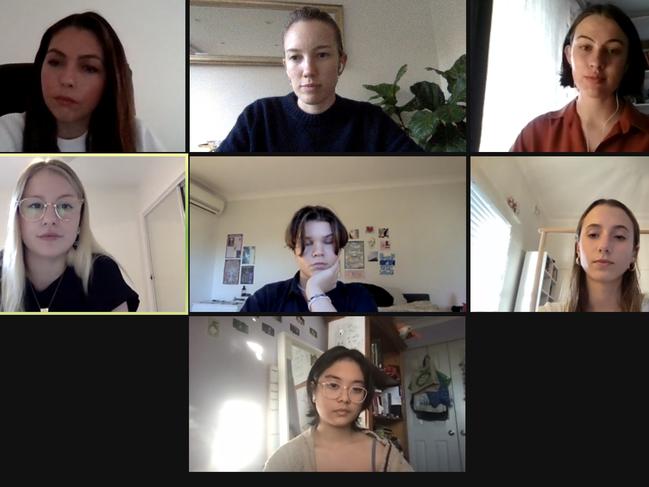

The Sunday Telegraph held an online discussion with students to glean what they wanted to know when it comes to sex, relationships and consent. Many agreed what they’d been taught was outdated. Watch the video.

NSW

Don't miss out on the headlines from NSW. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Students are crying out for more explicit sex education, including more real-world examples of sexual violence and fewer sanitised metaphors.

In a discussion with former and current students and survivor advocates, The Sunday Telegraph gained an insight into exactly what young people want to learn when it comes to relationship and sexuality education (RSE).

The interviews also revealed the glaring discrepancies between what is currently taught at NSW public, Catholic and independent schools.

Australia has been engaged in a national conversation about consent since thousands of students came forward with harrowing stories of sexual violence and harassment this year.

While state and federal governments have made changes to curriculums and created new resources – including the doomed “milkshake” video – students say they are is still missing the point.

“We have spoken so much about what we want to see and what we need to see but the government is refusing to act on it,” year 12 student Dani Villafana said.

“I think the biggest problem we are seeing is a lot of programs are being brought in by a lot of different people but they are not standardised.

“That means not everyone has access to the same quality of education.

“Not every school has the cops coming and talking to them, not every school has religion classes coming in and talking to them.”

Children are taught about stranger danger and how to say no when approached, Dani said, but the early consent lessons stopped there.

“Reflecting back on that, I think it was great we got that education when we were in primary school, aged four to 10,” said Dani, also a survivor of sexual violence.

“But then it seems a bit ridiculous they can‘t continue that education to apply to respectful relationships and not just to paedophilia.”

The Sunday Telegraph’s Matter of Respect campaign, supported by Rape and Sexual Assault Research and Advocacy, has been calling for an audit of how relationship and sex education is taught across all schools in NSW.

It is estimated that one in five Australian women have experienced sexual violence since the age of 15 and a majority of assaults occur at home.

Law and psychology student Amanda Matthews is a proud Aboriginal woman and victim-survivor advocate.

The 31-year-old paralegal said perpetrators were often presented as “monsters” – rather than friends, family members or partners.

“Victim survivors know that the people who abused them or the people who could abuse them are their friends,” the activist said.

“But the school education systems don’t address the people who commit these things as being one of us until after it has happened, not before.”

Teaching students about red-flag behaviours and that “anyone is capable of disrespecting your boundaries” would be more realistic, Ms Matthews said.

The education also needed to be trauma informed because it was highly likely there would be students in the classroom who had been victims of abuse, she added.

The NSW government in May announced an overhaul of the Personal Development, Health and Physical Education (PDHPE) lesson plans to include ways to practice and give consent and how to identify the body’s reaction to uncomfortable situations. But the lesson plans are not mandatory.

On the back of Chanel Contos’s petition calling for better consent education, and the outpouring of disclosures from students, Chloe Korbel, 16, lobbied her own school to change the way it taught students about relationships this year.

Chloe, who founded Youth Against Sexual Violence with Dani, said “you’re never taught sexual violence can be quite ambiguous”.

“We weren’t ever given specific examples of what consent looked like or coercion looked like or sexual assault or what to do in situations,” said Chloe, who is in year 11 at an all-girls Catholic school.

“I was taught self defence before I was taught consent.

“I think that is really telling because it’s putting the responsibility on us instead of the people perpetuating sexual violence.

“We need to be given more explicit examples of what it looks like.”

The last time co-ed Catholic school student Ethan Lyons, 15, remembers being taught about sex and development it was in year 7 or 8.

“It was really narrow and underlined the Catholic view around sex,” he said.

“I think the only discussions we’ve had about relationships were like friendships and social media, never really specific down to consent and respect relationships to do with sex.”

For 17-year-old Angela Weckert, a well-used but simplistic video comparing consent to a cup of tea was the extent of her consent education at school.

“We had sex education during a term in year 7 and 8 in PDHPE,” the public co-ed student from regional NSW said.

“The extent of that was looking at STIs and contraception methods, which is good in itself but our only real consent education was … comparing consent to tea.”

It is mandatory for schools to teach students about respectful relationships and sex in PDHPE, which becomes an optional subject from year 11.

The word ‘consent’ is mentioned in the NSW curriculum eight times but how deeply a teacher addresses the issue comes down to the individual school.

All agreed the education needed to be ongoing – not just taught once in year 7 – and should be supported by school culture, which meant getting teachers on board.

Some students The Sunday Telegraph interviewed believed the sex education offered in schools was “archaic” and based on old-school beliefs and situations.

University student and youth activist Elizabeth Payne, 21, said her sex education was very much framed around how to make a baby.

“It was very penetrative, penis and vagina sex, no mention of pleasure or queer sex,” she said. “Also things that tie into consent education and that being convinced to have sex is not consensual and affirmative consent.

“Maybe because someone is saying yes but their bodies and reactions are no.

“Having those really nuanced discussions, I would have appreciated more of that.”

Asked what other topics should be included in RSE, the answers included coercion, unconscious body cues, common responses to sexual assault such as fight, flight, freeze or fawn, slut-shaming and bystander intervention.

“Those examples are ones that actually relate to high schoolers’ lives,” Ms Payne said.

“They are not talking about having a baby. Yes that is relevant but it might not be to them right then.

“We also need to talk about nudes (photos) and online culture.

“We need to consider the realities of young people’s lives and to position them as victims in systems they haven’t been taught about.

“It‘s really important to do all that stuff that is really relevant to their lives right now.”

AUDIT CRUCIAL TO FIXING MESS

Katrina Marson

COMMENT

This roundtable demonstrates why a comprehensive audit of relationships and sexuality education (RSE) in NSW is so urgent.

The discrepancies between the sex ed experiences of the participants is dangerous. Young people shouldn‘t be getting wildly varying information about something so important to their personal safety.

Not to mention the content often seems frozen in time — some of them described sex ed that was identical to mine almost two decades ago.

Their experiences also showed why a new curriculum that emphasises consent is not enough.

This discussion shows that having fantastic resources and a good curriculum is all for nothing if you can’t guarantee that all young people will get the same quality RSE, frequently and from a young age. Or if you can’t guarantee the educators delivering it are trained to do so safely and effectively.

Until we know what is happening in every school in NSW, we can never make that guarantee — no matter how many times the word consent appears in the curriculum.

Katrina Marson is a criminal lawyer and lead researcher for primary prevention at Rape and Sexual Assault Research and Advocacy.

More Coverage

Read related topics:NSW consent laws