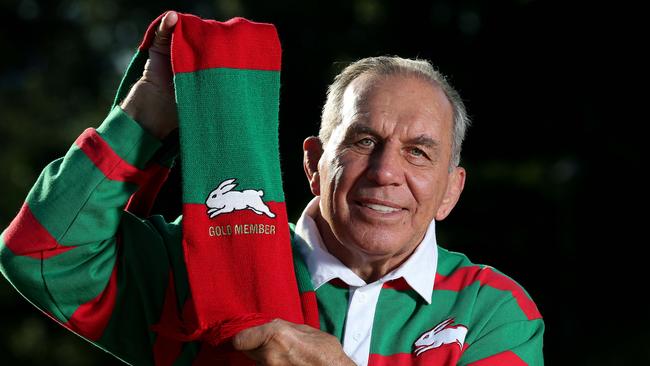

Souths legend John Sattler’s shuddering first-hand account of playing the 1970 rugby league Grand Final with a broken jaw: ‘Never show those opposition pr*cks you are hurt’

HOW Souths legend John Sattler played the last 77 minutes of the 1970 grand final with a shattered jaw — and himself into rugby league immortality.

NSW

Don't miss out on the headlines from NSW. Followed categories will be added to My News.

THE roar I hear is replaced by silence. I can’t see. Where am I? What the hell just happened? I blink, trying to kickstart my vision, but like a camera out of focus, all I see is a blur.

Through the haze, I make out a maroon object. A man, I think, with hair the colour of beach sand. I see this hotchpotch of colour running off into the distance.

Who is he? My senses are failing me and I feel vulnerable. Inside I scream: Help me … help me.

I have never felt pain like this in my life. It renders me impotent. Whatever just happened, my knees cannot withstand it. They buckle. Instinct takes hold. I think I feel blood coming from my mouth.

My vision slowly begins to sharpen. I still feel pain, excruciating pain. Mentally, my pain receptors try to locate the problem area. Pain in my head? No. It’s my jaw. Pain on the left side? Right side? Both.

Next step: assess the damage. I lift my hand to the side of my face. It feels fat, swollen. I place my thumb and index fingers around my chin and press firmly. My jaw wobbles like jelly, sending waves of pain shooting through my system.

I scream blue murder but my internal voice says: Stay calm, John, stay calm.

Curiosity gets the better of me and I lower my bottom lip, allowing just enough space for my index finger to probe the walls of my mouth. On the left side of my jaw I feel a hole that should not be there. A gush of blood spews onto my jumper.

I prod to the right — another hole. I work back to the middle of my mouth. I feel for teeth, which are still intact. I move lower, towards the gums. I feel a split, smack bang in the middle of my lower gumline.

I’ve broken my jaw in three places.

By now my vision is again sharp, my senses clear. I do a quick cognitive test.

My name is John Sattler. I am captain of the South Sydney Rabbitohs. I am standing in the middle of the Sydney Cricket Ground. We are playing Manly-Warringah in the 1970 NSW Rugby League Grand Final.

I look up at the game clock: just three minutes have elapsed. You’re kidding me! This ordeal already seems like it’s been going for hours.

My mind races. What do I do? I feel equal measures of fear, pain and fury, all wrapped up in a desire for vengeance. Only an idiot would play the remaining 77 minutes of the Grand Final nursing a jaw broken in three places. But I make my mind up anyway.

Like a crime-scene detective, I begin piecing together the sequence of events. I can see Manly is in possession. I make the assumption that I’ve run out of the line to make a tackle on a Sea Eagles player, who has smashed me.

I look up and scan the Manly formation for a potential suspect. I see one man running back into the line. He is wearing no. 11, my front-row rival. Sandy-coloured hair, just like the blur of colour I saw earlier.

He turns and fixes his eyes on me. It is the look of a guilty man, one acutely aware he has just got away with a savage footballing crime. His name is John Bucknall. He is the Manly forward who floored me with a vicious right hook that has left me with this shattered jaw.

You grub, I think. Nobody humiliates me.

In that moment, I plot revenge. The match officials might have let Bucknall off the hook, but I know the South Sydney pack will make the rest of his Grand Final a living hell.

I rise to my feet and the roar returns. Attempting to get my bearings, I stagger towards the wing and into the arms of Michael Cleary.

“Hold me up,’’ I mumble.

‘‘What do you mean?’’ Mike says, confused.

‘‘Hold me up … I’ve broken my jaw.’’

Mike grabs me by the shorts and takes a closer look. I open my mouth. I feel my lower jaw collapse like a deck of cards.

I see the whites in his eyes. ‘‘Jesus Christ, Satts!’’ Mike says, his confusion replaced by horror. ‘‘Get off the field. Get off! You can’t play on.’’

I tell Mike that going off is not an option. He knows my mantra, South Sydney’s mantra — never show those opposition pricks you are hurt. Walking off is tantamount to giving up. I’ve never been a quitter, and a cheap shot from John Bucknall isn’t about to make me one.

Thirty seconds of relief near the flanks is all I need, and I jog back to my defensive position. The pain throbs constantly, at times overwhelming me, but I find myself running on adrenalin. I say nothing. I don’t want the rest of the side knowing the truth, but Michael soon plays Chinese whispers and word reaches Bob McCarthy.

‘‘Hang in there, Satts,’’ Macca says as we walk to the next scrum. ‘‘We’ll get the bastard.’’

But I am facing another, perhaps greater, challenge: keeping my jaw in place. During breaks in play, I grab either side of it and jam it into place, then I clench my teeth against my thick white mouthguard, which I imagine is all that has saved me from even more catastrophic damage.

For the next 77 minutes, my focus must be on two things: one, winning a Grand Final. Two, maintaining pressure on my jaw. It is a draining process. At one point I instinctively suck in some air, and my jaw collapses.

I push it back into place, clench and go again. I look at the clock — just six minutes gone. This is agony. Every minute feels like an hour.

But if I’m going to stay on, I decide, I cannot hide. The ball is on my side of the field. I have to run, I have to test my jaw. I tuck the ball under my arm and run straight into the teeth of the Manly defence.

Who else should be there to greet me but two big forwards, John Morgan and John Bucknall.

Sensing an easy kill, they race in.

Bucknall arrives first. Crack!

He crunches me again, this time with a legitimate bone-jarring front-on tackle. Milliseconds later, Morgan joins in to wrap me up. Whack! I feel his fist make contact with my face.

Clearly, in the eyes of the Manly players, I’m now a wounded rabbit to the slaughter. The referee, Don Lancashire, blows his whistle.

He penalises Morgan, then calls him out and warns him for punching.

Two minutes later, I make my next run. Manly hooker Fred Jones sees it’s me and his eyes light up. He charges out of the line and we collide heavily. My jaw drops. I push and clench again.

In my mind, I convince myself I have survived the worst; that the Sea Eagles can only break my jaw so many times.

I retreat to our line, ready for more combat. Just 72 minutes to go.

Four minutes later, I miss a simple tackle while attempting to go around the bootlaces. My front-row partner, John O’Neill, gives me a serve. Lurch, usually the last to know anything, is none the wiser about my broken jaw.

‘‘You can’t miss a tackle like that. It’s a Grand Final!’’ he fumes.

McCarthy hears the blast. At the next scrum, he walks over to Lurch. ‘‘Hey, Lurch, go easy on Satts,’’ he says. ‘‘You know he’s got a broken jaw.’’

Lurch takes a closer look as we prepare to lock arms at the scrum. I see the anger in my old mate’s eyes.

‘‘Right, listen here,’’ Lurch says, pointing at me. ‘‘From here on in, you get out of the road. I’m telling you, Satts, stay out of the way, I’ll take the hit-ups.’’

That moment typifies our mateship at Souths. If you are going to war, John O’Neill is a man you want beside you in the trenches.

I agree with Lurch, all the while planning to defy him. I know this won’t be one of my finest performances, but I am determined at least to hold my own.

By the 22nd minute, Bucknall and I are now officially at war. We prepare for a scrum. It collapses. As we attempt to reset, Bucknall lunges at me and pushes me to the ground. He’s bullying me, making me look weak again, and the crowd roars.

The scrum packs down. Again, it is messy. Bucknall loses his balance and drops to his knees. Momentum forces his head to the ground, resting right in front of my hard leather boots. I don’t need a second invitation.

I’m tempted to take a wild swing and boot Bucknall so hard that I knock the bastard into next week. But that could get me sent off, and be further ammunition for the Sea Eagles.

Worse, it could cost us the Grand Final, a scenario I cannot swallow after our self-inflicted implosion against the Tigers just 12 months ago.

No, I must be more discreet.

I watch the referee. When Lancashire looks away, I get square.

Whack! My kick is short and swift and hits him between the eyes. Cop that. Bucknall groans, then rises to his feet, furious. We engage in a bit of push-and-shove before play continues.

Sixty seconds later, at the next scrum, Lancashire stops play and calls us out. He missed my sly kick to Bucknall’s melon, but the touch judges saw our post-scrum skirmish.

‘‘You two, cool it,’’ Lancashire says in a short tone. ‘‘The next bloke who does anything stupid is off.’’

Bucknall doesn’t even survive until half time. He is not guilty of a brain explosion but the victim of South Sydney gang warfare.

In the 31st minute, he runs to the line and is hit in a textbook front on tackle by Macca, who drives him forcefully into the ground.

Bucknall screams and reaches for his lower back. He eventually rises but, like me, he is now under siege.

Three minutes later, he makes another hit-up close to the Manly line. Gary Stevens, our hard-as-nails back-rower, charges in and crunches him with full force. Bucknall manages to play the ball, then slumps to the turf, shaking his head and clutching his shoulder. He is finished.

As Bucknall trudges off, I manage a wry smile. I have won the battle, and now Souths are going to win this war.

*****

THE COACH walks into the shower area. I stand, jaw clenched, staring back at him. I feel like a six-year-old who has just been caught with his hand in the cookie jar.

“Satts, is it true?’’ Clive Churchill asks. ‘‘Give me a look.’’

I open my mouth to reveal two large cracks and a split down the middle of my jaw. I feel my teeth jutting out at all sorts of angles.

“You can’t go back out,’’ Clive says, in an almost pleading tone.

Reluctantly, Clive relents. A choir of tapping studs is my signal to bolt out of the showers and past the selectors, and I rejoin my teammates back on the SCG.

Within 60 seconds, I question the wisdom of my decision. The ball comes my way, a perfectly timed pass straight onto my chest. I drop it cold. As I open my mouth to curse, my jaw collapses again. Push, clench, hold.

With each passing minute, the pain amplifies; adrenalin can only last so long. My biggest test comes 11 minutes from time. We are leading 18—12 when Manly’s speedy winger Derek Moritz bolts into open space. I chase and chase, and my jaw feels the thud of every step. The cover comes across at the same time and we ground him.

I rise. Now I’m in real agony, and I want the game to end. And when Bobby Grant seals our 23—12 victory with a dummy-half dash six minutes from time, I switch off mentally, not wishing to consider the pain that lies ahead.

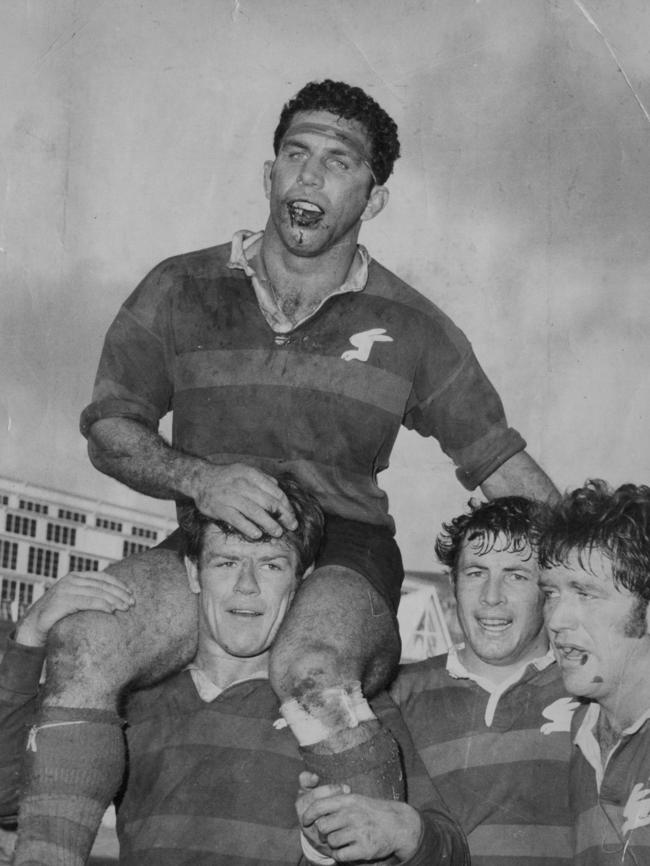

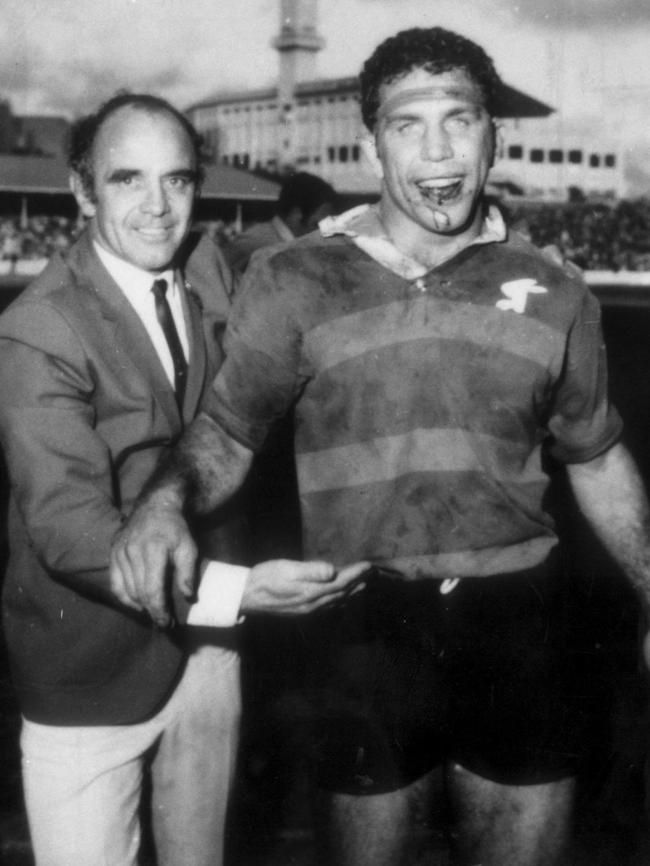

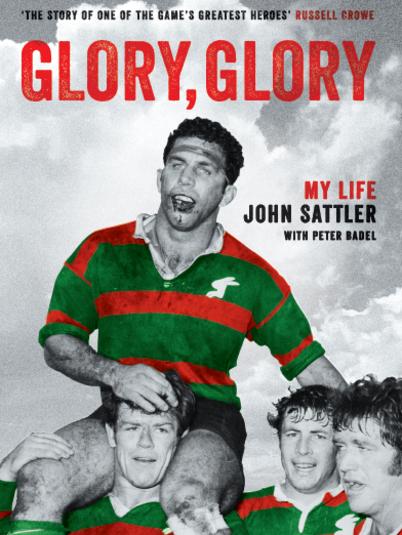

The siren sounds. We have done it again — premiers three times in four seasons, exorcising the demons of 1969. But I can barely stand, let alone celebrate. Seventy-seven minutes with a broken jaw. I made it. Macca rushes over and I am lifted onto his shoulders.

Exhausted, and with my jumper soaked in blood, I give his forehead a pat as I am carried off the field.

A little later, Clive rushes over and hugs me, in the process accidentally hitting me in the chops. My jaw flops again. Thanks, coach.

****

ON THE BACK page of The Sunday Mirror is a photo of me being chaired off the SCG by Macca, with the blazing headline ‘BROKEN JAW HERO’. Seeing my bravery etched in black ink makes

me smile — as much as I can, anyway.

I then scan the match statistics and my satisfaction levels soar. In eighty minutes, I made 20 tackles, touched the ball 29 times and managed one offload and eight hit-ups for 39 metres.

I missed two tackles and had one handling error. The stats are proof I am no pea-heart. Manly could not send me into hiding.

My recovery spanned three months. I lost no teeth, but they were all askew and I needed several sessions of dental work to reset them. Some nights I had nightmares — probably of John Bucknall bashing me — and I would wake to find the wiring had been ripped apart.

The time convalescing afforded me the opportunity to watch a replay of the moment Bucknall rearranged my face. I remembered the blur of colour. But watching it through the eyes of the TV camera finally allowed me to join the dots.

Now I saw it clearly: Manly received a tap in their half. Bill Hamilton took a pass and I saw Bucknall steaming up in support. I believed he would get the ball, and moved in to tackle him. He didn’t get it, so I eased up as we collided.

I prepared to make my way back into the defensive line when Bucknall hit me with a brutal swinging forearm. It was a blow I simply never saw. My knees buckled, then Bucknall jolted my jaw again as he manhandled me, before I staggered back into the defensive line.

From that day I wondered if the attack on me was deliberate, premeditated. One day some 40 years later I bumped into Ron Willey, Manly’s coach in 1970, and he opened up.

“I told Bucknall to get out there and get you off the field,’’ he revealed. ‘‘I told John, ‘If the opportunity comes, make sure you take John Sattler out’. I’m sorry, Satts, I didn’t know the damage it would do. I have to put my hand up for that.’’

There were some attempts to smooth the waters between Bucknall and me. One former Manly player tried to set up a meeting between the pair of us to call a truce, but I wanted nothing to do with it. We never spoke.

For over 30 years Bucknall never said a word about the incident.

Then, one day, I picked up the paper and came across an article detailing his explanation for breaking my jaw.

‘‘I was no villain,’’ he said. ‘‘Far from it. I was just protecting my captain Fred Jones. I was just doing my job. Souths were also out to get me and I got hit hard three times. I can’t even remember who got me but I came off with a badly damaged shoulder. Still, I’ve got no hard feelings.’’

The truth is that Souths were only out to get Bucknall because he had assaulted me. He was a victim of his own actions. He should have no hard feelings.

By nature, I am one to let bygones be bygones, and I don’t see the sense in holding grudges. Some people might even argue that Bucknall did me a favour, in a strange way. The incident was the making of me, they say, given the manner in which I have since been glorified for playing 77 minutes with a broken jaw.

Do I hate Bucknall? No, I don’t. Have I forgiven him? Yes, I have. Would I rewrite history and erase the moment I broke my jaw? No, I wouldn’t.

Time has healed my wounds, in all senses. But let me say this: I’m glad it happened only once in my lifetime.

I wouldn’t wish that broken jaw on my worst enemy … not even John Bucknall.

— as told to Peter Badel

But I am facing another, perhaps greater, challenge: keeping my jaw in place. During breaks in play, I grab either side of it and jam it into place, then I clench my teeth against my thick white mouthguard, which I imagine is all that has saved me from even more catastrophic damage.

But I am facing another, perhaps greater, challenge: keeping my jaw in place. During breaks in play, I grab either side of it and jam it into place, then I clench my teeth against my thick white mouthguard, which I imagine is all that has saved me from even more catastrophic damage.