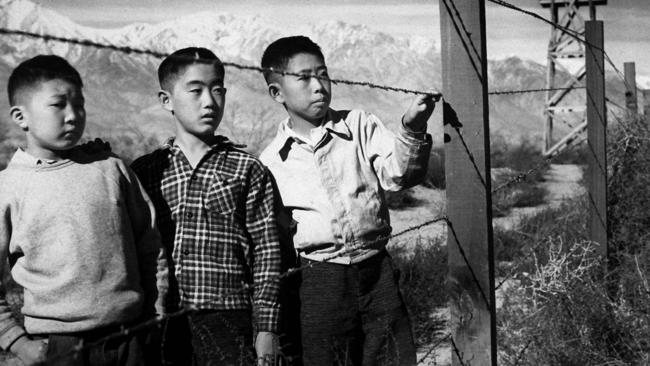

Son of Japanese immigrants challenged the legality of wartime detentions

When police arrested a young man with Japanese features in California in 1942 it triggered legal challenges to the detention of Japanese people during the war

Californian police were patrolling the town of San Leandro one afternoon in May, 1942, when they spotted a young man with Japanese features walking with his girlfriend.

Ordinarily that would not have been a problem but things had changed after December 1941 when the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor drew the US into a war. In May 1942 General John DeWitt, head of the Western Defence Command, had issued exclusion order No.34 that “any person of Japanese ancestry” within certain areas under his command were to be evacuated by May 9. This young man was in violation of that order.

The police asked him for ID and he showed them a draft registration card identifying him as “Clyde Sarah” a man of Spanish-Hawaiian ancestry.

But the card looked like it had been altered and when the officers asked him questions in Spanish he was unable to answer. He confessed his real name was Fred Toyosaburo Korematsu, the son of Japanese immigrant parents.

He was arrested and turned over to the FBI. A local paper reported the incident as “Jap spy arrested in San Leandro”, but he was definitely no spy. Korematsu, born a century ago today, was a loyal American citizen, but one who found the detentions unjust and racist. He was later put on trial, but challenged the legality of DeWitt’s exclusion order.

He was born Toyosaburo Korematsu on January 30, 1919, in Oakland, California. His parents, Kakusaburo Korematsu and Kotsui Aoki, had immigrated to the US from Japan in 1905. They had established a successful plant nursery business. At school one of Toyosaburo’s teachers found his name difficult to pronounce, so she dubbed him Fred.

In high school in 1934 when army recruitment officers handed out flyers to his classmates they refused to give him one. He was told they were under orders not accept Japanese students.

After graduating from high school he went to college but dropped out because of financial problems. He took a course at the Master School of Welding in Oakland and got a shipyard job, joining the Boiler Makers Union.

When requested to present himself for military service under the Selective Training and Service Act of 1940, he did so but was rejected on health grounds. When war broke out

in 1941 Korematsu was again rejected for military service, but felt he contributed to the war effort through his welding job. But one day he turned up to work to find his time card missing and a note to report to his union representative. He was dismissed from the union and lost his job.

In March of 1942 DeWitt issued the first directive for Japanese people on the western seaboard to register and prepare to be resettled further inland. In May he issued his order calling for the removal of Japanese from exclusion zones.

Korematsu’s family closed their business and went to a resettlement centre, but Fred stayed behind to earn money to take his girlfriend Ida Boitano, the daughter of Italian immigrants, to the midwest to live. At the time in California it was illegal for them to marry because Korematsu was not “white” and he wanted to move to a state where it was legal. He even had surgery on his eyes to make himself look less Japanese to avoid being forcibly evacuated, but on May 30 he was arrested.

Found guilty of violating the exclusion order he was given five years probation and sent to Central Utah War Relocation Centre in Topaz, Utah, where he lived in terrible conditions, being forced to work for low pay. Ida also broke off their engagement.

The American Civil Liberties Union helped appeal his case on the grounds the exclusion order violated his constitutional rights. It went to the supreme court in 1944 but Korematsu lost. The judges voted 6-3 against.

After the war Korematsu tried to return to normal life. He married Kathryn Pearson in Michigan in 1949 and later settled back in Oakland. But his federal conviction stayed on his record, preventing him from getting a real estate licence. In 1976 president Gerald Ford admitted wartime detentions had been wrong, leading to an inquiry into detentions in the 1980s. In 1983 Fred’s case was reopened and his conviction was overturned.

In 1998 he received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from president Bill Clinton. He died in 2005 but in 2018 the US Supreme Court repudiated the 1944 decision while ruling on the legality of President Donald Trump’s executive order on banning certain people entering the US.