Secretive Mexican clinic claims to have shrunk fatal brain tumour in Australian girl

IT’S a secretive Mexican clinic where the doctors refuse to co-operate with the international medical community, but the family of a five- year-old Australian girl claim her fatal brain tumour has gone after $300,0000 worth of experimental chemotherapy.

NSW

Don't miss out on the headlines from NSW. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- Why Aussies are heading to Mexico for brain cancer treatment

- $100 million National Brain Cancer Mission a huge victory

THE family of an Australian girl being treated for a fatal brain tumour in a secretive Mexican clinic have reported her cancer has gone.

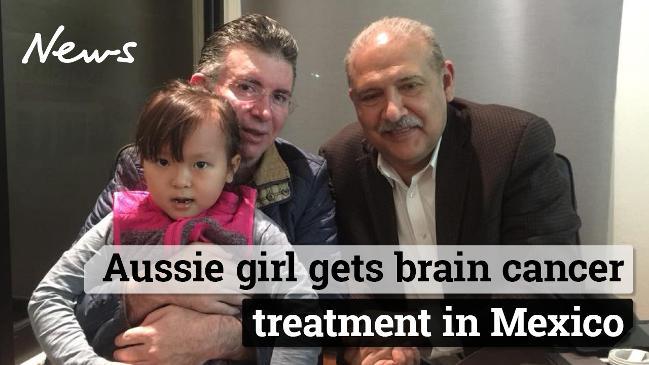

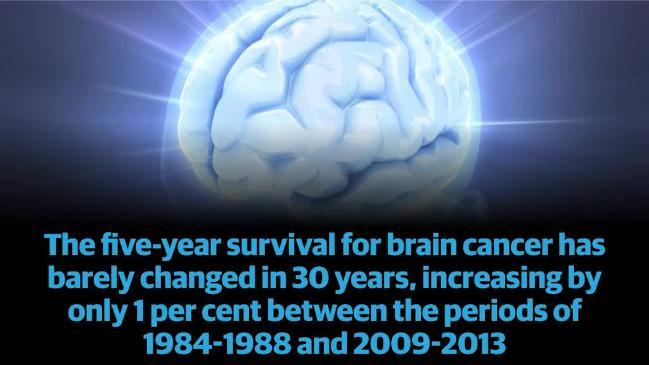

Three years ago, Annabelle Nguyen, now five, was diagnosed with the inoperable and deadly diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG). Doctors in Perth told her parents Sandy and Henry it was incurable and their child had six to nine months to live.

The Nguyen family turned to Mexico to undergo experimental intra-arterial chemotherapy and immunotherapy at a clinic in Monterrey run by doctors Alberto Siller and Alberto Garcia.

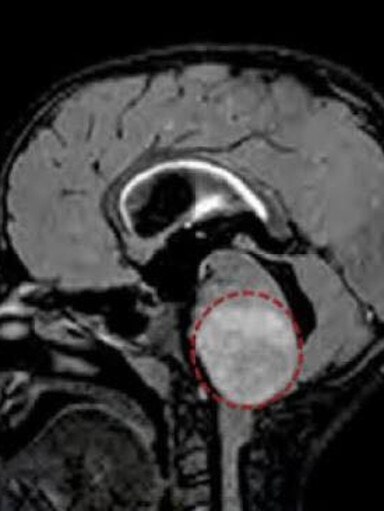

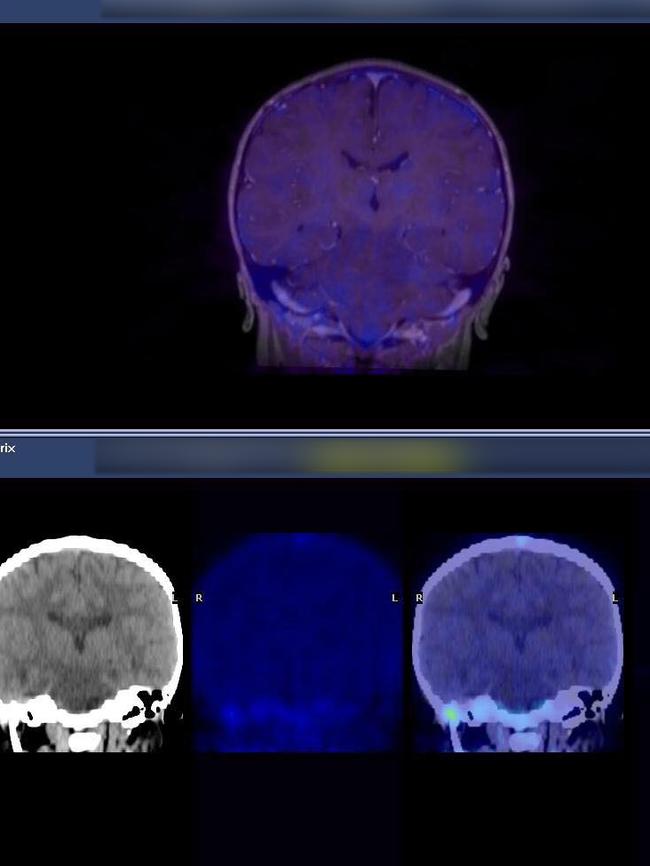

Before her first treatment in May last year, her MRI showed the tumour clearly in her brain stem and growing rapidly. But Annabelle’s parents say after 10 treatments, which has cost the family in excess of $300,000, her latest MRI and super PET scans show there is no tumour and no evidence of disease.

Speaking from Mexico, Sandy Nguyen said it was worth every cent to still have their child.

“The results from these tests confirmed what the doctors expected, and it’s wonderful. Annabelle has no tumour activity in her brain,” Mrs Nguyen said.

“It is so surreal, I can’t believe it after almost 29 months, and moving from country to country, we sold our property and lost hope. What this means is that we can officially say that Annabelle has no evidence of disease. She has beaten the DIPG beast.”

The doctors, who use a combination of immunotherapy and inter-arterial chemotherapy that feeds a cocktail of chemotherapy drugs through the artery directly into the brain tumour region, have refused to co-operate with the international medical and scientific community. They have not published any data on their techniques or success rate. Many children at the clinic do not survive.

Adelaide mother Hayley Keeping took her daughter Alexia Eljourdi to Mexico last year, but after four treatments the family ran out of money and had to come home. Alexia, aged five, died a month later.

After weeks of negotiation doctors Siller and Garcia had agreed to an interview with the Sunday Telegraph but did not follow through. They have not answered emails or calls.

Mrs Nguyen is planning to bring Annabelle back to Australia next week, where she hopes Australian doctors will confirm the Mexican scans. She said they hoped to travel back to Mexico every six weeks to continue with the treatments, which cost $30,000 a round.

Annabelle is the second child to report no evidence of disease from the clinic.

Eight-year-old Braden (Buddy) Miller from Michigan, in the US, was diagnosed with DIPG in January 2017 and scans now show his tumour is gone.

Leading Sydney paediatric oncologist Professor David Ziegler does not blame desperate parents seeking hope, but cautioned the scans used in Mexico to claim no evidence of disease could be misleading.

“In terms of internationally accepted practice for DIPG patients, it is best practice to monitor for responses to treatment using MRI scans,” he said.

“PET scans are not helpful as DIPG tumours do not usually ‘light up’ using this method and therefore these scans may appear to be negative, even when tumour is present.”

Dr Ziegler said in terms of the treatment occurring in Mexico, there is currently no evidence to support it is effective for patients with DIPG”.

“How do I know the results are real? Well, I just have to trust,” Mrs Nguyen said.