Royal Commission into Child Abuse: ‘Forgotten Australians’ call for day of recognition

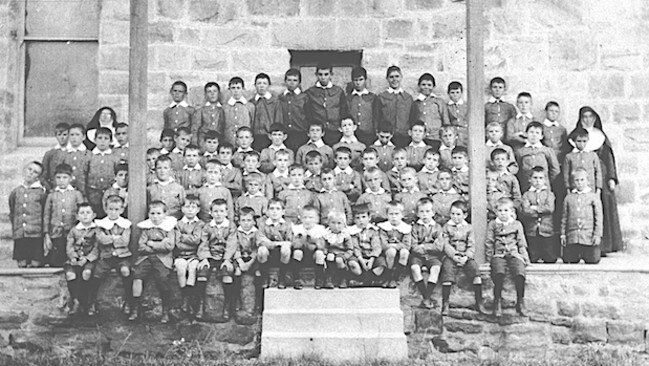

THEY’RE the “forgotten Australians” — half a million children removed from the family home by courts for their own good. Instead they received years of sexual and physical abuse and now ahead of this week’s Royal Commission, they’re seeking a national day of recognition.

NSW

Don't miss out on the headlines from NSW. Followed categories will be added to My News.

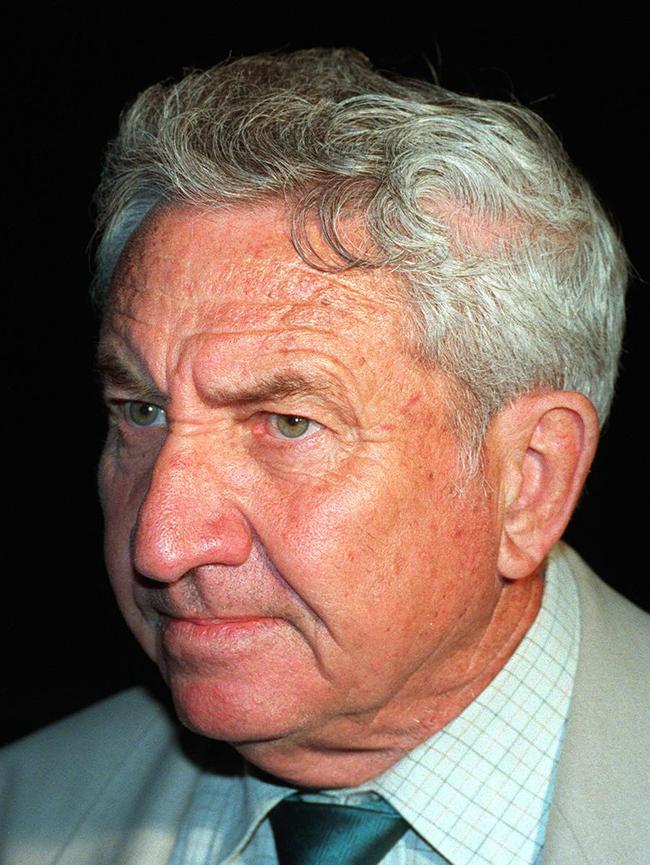

RAY Leary and his brother Ken are “forgotten Australians”.

They’re part of a generation of children — approximately half a million boys and girls — removed from their homes by the police and courts and institutionalised between the 1920s and 80s, where an overwhelming number of children suffered physical, mental and sexual abuse at the hands of their supposed carers.

“For years, I carried the scars (of what) happened to me, what happened to me in that shed ... It should never have happened,” Ray Leary said.

“I’ve had the cane, I’ve been locked under the stairwell for punishment, the door was locked ... I’m scared of the dark now, because of those steps.”

After being removed from home aged six, it was a string of Church run institutes before, Ray found himself at the Werrington Park children’s home in St Marys. There he was subjected to not just strict classroom discipline but the attentions of a group of paedophiles, including his own social worker Ian Hughes, the infamous Robert “Dolly” Dunn and Wollongong Mayor Frank Arkell.

“There are the Stolen Generation, we’re the Forgotten Australians,” he said.

“We were taken into state care to be looked after because our parents couldn’t do a better job — we were young kids, kids who are supposed to enjoy themselves. Unfortunately myself, my brother, my sister — we’ve all been through it, y’know?”

READ MORE: Sex crime crackdown proposes jail over ‘failing to protect children’

For 60 years, government policy was to forcibly remove children at risk or living in poverty or neglect and Relationships Australia estimates 500,000 boys and girls were damned to unspeakable abuse in institutions and foster families.

With the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse handing down its findings this week, Relationships Australia and Wattle Place, which offers counselling and resources for victims of institutional abuse, tasked freelance journalist Kim Camberg with documenting some of these shocking stories of abuse and neglect.

“It’s astounding, these harrowing stories — but they’re very much still the forgotten stories, the forgotten Australians,” she said.

Ray, his brother, and a host of other survivors recount their never before heard stories — the Commission could only hear from a fraction of the victims — as part of Ms Camberg’s Forgotten Australians documentary.

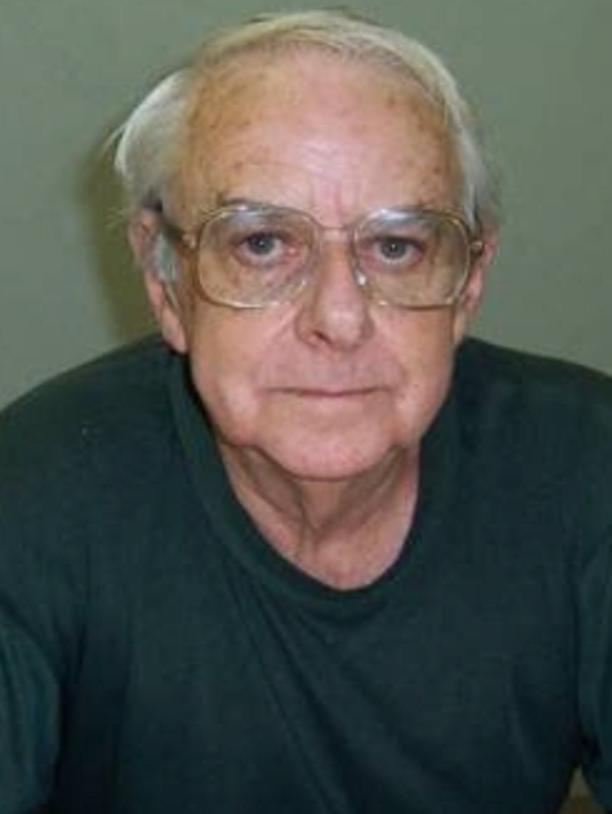

Ray’s older brother, Ken, now in his 60s, is still traumatised by his treatment at the infamous Mittagong Boys Home in the Southern Highlands.

“I didn’t have anyone who wanted me,” he says in the documentary.

He and his brother are now getting help through Relationships Australia and the Wattle Place community centre in an effort to come to grips with the abuse heaped on them.

“I feel Wattle Place ... we need places like this for Forgotten Australians now. With all the abuse and the reliving of our stories to the Royal commission, and letting the community know,” Ray Leary said.

“The community will know now, (it’s) too late for us, but hopefully, with our stories it will

never happen again.”

That’s why the survivors of Wattle Place want a national day of remembrance — Forget Me Not Day on December 15 — to ensure their stories are remembered and are never replicated.

“I am a Forgotten Australian. I embrace it,” fellow survivor Mary Brownlee said.

Ms Brownlee’s Irish Catholic parents immigrated to Australia in the 1950s hoping for a new life, but were soon stuck in a cycle of poverty.

She and her four brothers were taken away by police and subjected to years of sexual and physical abuse.

In the documentary, she recounts her sexual abuse at the hands of “the bad man” at just age nine.

“What the Australian public, what I’d like them to understand is that we aren’t

victims,” she said.

“We are people who are on our journey to just heal our development stages that we lost.”