PM Malcolm Turnbull’s new secrecy laws fly in the face of principles he was once acclaimed for

A BRAVE Malcolm Turnbull once fought the British government to publish official secrets. Now 30 years later, the Prime Minister’s new laws would jail journalists and suppress the truth.

NSW

Don't miss out on the headlines from NSW. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- Five minutes overtime a day causing train chaos

- How Crocodile Dundee was made on a tiny budget

- Shares plunge on Trump’s inflation hangover

MALCOLM Turnbull has introduced authoritarian laws to “criminalise ordinary journalism” that fly in the face of principles he won worldwide acclaim fighting for in the Spycatcher case against Margaret Thatcher’s government.

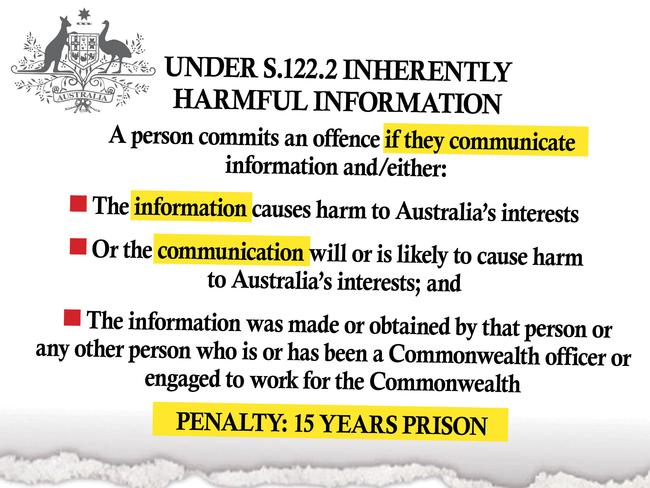

The Prime Minister has come under fire for his proposed secrecy laws — introduced amid the historic marriage equality celebrations on the final day of Parliament last year — which threaten a 15-year prison sentence for journalists or editors who are given classified documents not deemed by the government to be in the public interest.

Mr Turnbull made world headlines as the talented lawyer fighting for the Australian publication of former MI5 officer Peter Wright’s memoirs, Spycatcher, when the British government was trying to ban it in September 1987 because of intelligence it contained.

Opposition Attorney-General Mark Dreyfus told The Daily Telegraph Mr Turnbull had abandoned the values he fought for in the Spycatcher case with these new laws.

“If British law had taken the same form as these proposed laws, Turnbull would have lost the Spycatcher case,” he said. “He’s no longer upholding the principles he fought for in 1987.”

Mr Turnbull’s battle was to fight the suppression of national secrets, based on the argument they were already in the public domain and would not damage MI5’s reputation.

“He (Wright) had been privy to some of the weightiest secrets of the free world, he had spied on presidents and prime ministers, he was at the very centre of the fight against the Soviets, the IRA and any other enemies of Britain,” Mr Turnbull said of Wright’s access to intelligence in his book, The Spycatcher Trial.

In interviews at the time, Mr Turnbull said: “Just looking at the issue of principle, surely the issue of principle is whether you have a sensible approach to official secrets.”

Yet, the legislation he introduced into Parliament seeks to slap a 15 year jail sentence on journalists, editors and their lawyers for receiving — not even publishing — classified information.

And while Attorney-General Christian Porter yesterday left the door open to amending the legislation, conceding it was not perfect, the government’s position is that it is problematic to provide an exemption to the entire media.

“I have concerns, I do have a few. I think that there are some areas where obvious improvements could potentially be made to the drafting,” Mr Porter said.

A government spokesman rejected the Spycatcher comparison, saying it was a book about the intelligence services of another nation and centred on a spy not a journalist.

The spokesman added three books have been published about ASIO in recent years and they would not be banned under the new laws.

It comes as the Office of the Intelligence and Security has confirmed it was not consulted on the contentious new laws, that could also mean its officers are subject to a criminal offence for handling classified material.

The Deputy Inspector-General of Intelligence, Jake Blight said he was not consulted about the espionage and foreign interference bill — despite his office being responsible for ensuring the “legality and propriety” of the intelligence community.

He confirmed IGIS first saw the legislation “the day it was tabled in Parliament. That’s the day we saw it.” “The bills that are before the committee today we were not consulted on,” he told the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security.

“There may have been (discussion about it), but our office wasn’t involved.”

Mr Dreyfus said this was a “first” for the Australian Government to choose to “create a criminal offence out of innocent receipt of documents.”

“It criminalises ordinary journalism,” he said. “They have chosen to completely amend all of the secrecy provisions that have been in the crime’s act since 1914, amended in 1960, not touched since.

“(Look at) the care that the Howard Government took over the introduction of the criminal code, compared with this hasty, rushed legislation brought into the parliament at five minutes to midnight on the last day of sittings last year.”

Concerns about the legislation have been raised by security experts, media organisations and academics, with alarm that any journalist handling classified information may fall foul of the law and face up to 15 years in jail.

Media, Entertainment and Arts Alliance boss Paul Murphy told the inquiry it “criminalises journalism” and elements of the bill criminalised “whistleblowers (who) bring material to journalists for public interest reporting.”

Foxtel has also warned that the laws threatened broadcasting of its BBC, Al Jazeera, or other state news channels which could be considered “soft diplomacy tools”.

“We would have to monitor those channels 24 hours a day with subject matter experts who were capable of recognising when such an incident arose in order to be able to monitor it,” Foxtel corporate affairs director Bruce Meagher told the inquiry.