Plain-speaking in court spares kids trauma as they give evidence

A LEGAL revolution of compassion and commonsense under way in NSW will finally give children a powerful voice in our courts and could put more abusers behind bars.

NSW

Don't miss out on the headlines from NSW. Followed categories will be added to My News.

IN a corner of Sydney’s busy Downing Centre courts, dogs, dolls and fidget spinners are replacing bibles and wigs. Crimes are plotted on storyboards, key players are drawn in stick figures, and lawyers replace legal jargon with straight talk.

In these rooms, minors as young as three give evidence in sexual abuse cases. But with one key difference — each is supported by an adult trained in child development, who ensures that they understand every step of the process.

Since the child evidence pilot began 18 months ago, the improvement in the clarity of the children’s evidence and the reduction in their trauma has been so startling that the pilot’s rollout is being fast-tracked amid fears that kids in the old system are disadvantaged.

“It is going fantastically,” said Judge Kate Traill, one of two judges involved.

“We are getting evidence from children, particularly young children, that without the use of an intermediary, it would be unlikely that they could give their evidence with such clarity.”

The trauma of testifying in court has long been one of the main reasons why families of sexual abuse victims don’t pursue justice. In NSW, fewer than 20 per cent of all reported child abuse incidents proceed to court.

The process has improved since the 1980s, when child witnesses were required to swear a formal oath on the bible, to take the stand before the jury, and to eyeball both a hostile barrister and the person accused of assaulting them.

But it’s still traumatic. While children now give evidence via video link from a remote room, they must sit and watch their police interview first — which might take hours — and then face cross-examination while a jury watches on.

The trial might be two years after the incident, which is half a lifetime for some kids, and the cross examination is conducted in legalese, with little attempt to simplify the questions so that the children can understand them.

Few kids understand the questions, but feel they should answer them anyway.

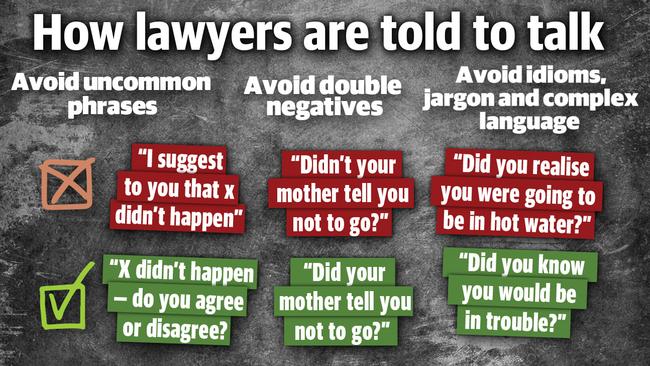

Barristers use unfamiliar phrases — “I put it to you” is a popular one — and confusing double negatives, such as, “didn’t your mother tell you not to go?” They are trained to speak this way to control the evidence, but many witnesses — even adult ones — don’t understand it.

“Lawyers are operating in a language that is very familiar to them,” said Professor Judy Cashmore, a member of the NSW Judicial Commission.

“If you are immersed in a language you think is clear, you probably don’t understand that others find it difficult.”

Few kids understand the questions, but feel they should answer them anyway.

So they often give inconsistent answers, which can cause their evidence to be confusing and therefore dismissed as unreliable, which in turn reduces the chances of conviction.

Studies since the 1980s have shown that children don’t understand legalese, and that court experience itself is not as traumatising as the feeling that they are not being heard, understood or believed.

Simple language sounds like common sense. “A lot of it is common sense,” said Judge Traill. “Adults could do with this.” But it wasn’t until this pilot project began in March last year that NSW Courts actually tackled the problem.

Under the pilot, which is only operating in the Kogarah, Bankstown, Chatswood and Newcastle Child Abuse Squad districts, child witnesses are paired with an intermediary trained in psychology or occupational therapy.

The intermediary’s first job is to assess the child’s abilities ahead of the police interview, which is recorded as evidence in chief.

They have the enthusiastic support of police.

They test how well a child tells a story, or whether they understand words such as on or off, lying down or behind.

“How well can they sequence? How well can they give a description of something or someone?” said Rukiya Stein, an intermediary and qualified speech pathologist. They might use storyboards or timelines to help the children express themselves.

“I’ve used sequencing charts, or coloured Post-It notes for multiple events. We often use visual timelines — ‘this year you are in year eight, last year you were in year seven’.

“We are impartial — we are just facilitating communication.”

They have the enthusiastic support of police.

“The kid might have cerebral palsy, so the intermediary gives us some insight into how to best interview that child,” said the head of the child abuse squad, Detective Chief Inspector Peter Yeomans.

“We are achieving better evidence, and reducing trauma to the victim.”

The intermediaries do another assessment before the defence’s cross-examination is prerecorded, then provide a report for the judge on what the child needs. Most reports suggest simple language, but sometimes they will go further.

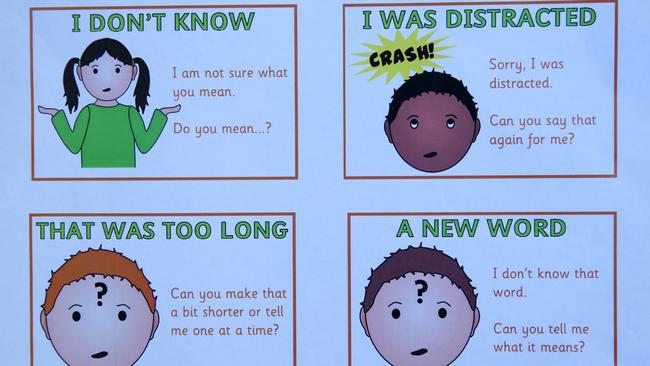

If a child struggles with words, the intermediary might suggest a doll to show where they were touched. They might recommend visual memory aids. Some might need reminder cards to say ‘I don’t know’ or ‘please wait, I’m thinking’.

“You think that would be obvious, but there are a lot of children that just agree with a question,” says Ms Stein. “For some it’s a cultural thing, they won’t say to an adult, ‘please wait’. If they point to the note, I can raise it with [the judge].”

She is studying the pilot’s impact on court outcomes

Intermediaries help with stress relief, too. “I have a koosh ball that kids love, a fidget spinner, playdough, a fidget cube, that they can play with in their hands to avoid anxiety,” Ms Stein said. Some kids have been allowed dogs in the prerecording room.

Only the witness, their support person, the intermediary and a court officer are allowed in the room. The judge and barristers communicate via video link from the courtroom, and usually don’t wear wigs or robes to avoid distressing the child.

The cross-examination is recorded about two months after the complaint is made, so the memory is still fresh in the child’s mind. It also lets them put a stressful period behind them. Instead, the video is played at trial, which takes place up to two years later.

An evaluation in July found everyone, including defence barristers, had embraced the changes. Professor Cashmore has been asked to bring forward her final assessment of the trial in the hope of an earlier rollout.

She is studying the pilot’s impact on court outcomes to see if it reduces delays, or if clearer evidence from children increases early plea rates.

“We find barristers in the pilot are starting to modify how they ask questions.”

“Because they are able to articulate and have it made clear what they are really saying, does that translate into a higher guilty plea rate?” she says.

“The other possibility is that if the children are able to give better evidence, are the police are more likely to take the case forward for prosecution?”

Some believe the plain-speaking from the pilot should be extended to the rest of the justice system, because so many witnesses are non-native English speakers, or poorly educated, or too nervous to understand the barrister’s questions.

RELATED:

“It’s in everyone’s interests, and the interests of justice, for a question to be comprehensible to those who are being asked to answer them,” said Professor Cashmore.

But the lesson already seems to be catching on.

“We find barristers in the pilot are starting to modify how they ask questions [in other courts], because they realise how simple and easy it is to be clear and precise,” said Judge Traill.

Attorney General Mark Speakman said there have been 144 pre-recorded hearings since the pilot began.

“The overwhelming support of the pilot is very encouraging, and consequently the final evaluation ... has already been brought forward to next year.”