The Children’s Hospital at Westmead open promising ONC201 trial for brain cancer kids

A new international drug trial for the deadly DIPG cancer that claims the lives of 20 children a year has finally opened in Sydney offering hope to families who had previously been told there was nothing that could help.

NSW

Don't miss out on the headlines from NSW. Followed categories will be added to My News.

A new international clinical trial will offer hope to Australian children with the deadly brain cancer diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG) and diffuse midline gliomas.

Children with DIPG are given nine to 12 months survival after diagnosis and the devastating cancer kills around 20 children a year in Australia.

Now the Pacific paediatric Neuro-Oncology Consortium (PNOC) has opened the PNOC-022 trial to test promising new drug combinations, including the drug ONC201.

“Participation in this trial will enable immediate access to a new and promising treatment strategy desperately needed for Australian and New Zealand children diagnosed with this deadly form of brain cancer,” lead investigator Associate Professor Geoff McCowage said.

“The Children’s Hospital at Westmead is the first hospital in Australia to offer PNOC-022, with other children’s cancer centres throughout Australia and New Zealand opening the trial in the coming months.”

To date, there has been little on offer to children whose parents have been told to go home and make memories.

Some families have been able to get hold of ONC201, by importing it from Germany, but children in the trial will be able to access the drugs here.

Angie Sari-Daher, whose daughter six-year-old Eve was diagnosed in March 2021, has started a petition to emphasise the urgency to have these clinical trials open to Australian families.

“Our kids are dying because they can’t access these trials or medications. We need to change this,” the petition reads.

Ms Sari-Daher has been importing the ONC201 drug from Germany at a cost of $3000 a month which sadly precludes Eve from the trial.

“It is fantastic for the other families, but we’re not going to be eligible, but it is great there’s some options for other kids. We are trying to get on other trials,” she said.

“All children will be treated with the drug ONC201 and combined with novel agents that have shown additive or synergistic effects in preclinical models,” A/Prof McCowage said.

‘It’s exciting this is starting at Westmead Children’s because for decades we’ve tried one drug after another and nothing has delivered and all we’ve had was radiation which controls it for a little while and inevitably it grows back and is lethal, so finally we’ve got this drug ONC201 and we can finally access the drug.”

Lead investigator of the preclinical trials of ONC201, Dr Matt Dun from the Hunter Medical Research Institute found the combination of drugs offered hope to children who would otherwise die.

Dr Dunn’s own daughter Josephine died of DIPG in 2019, aged four. She lived for 22 months after diagnosis.

“The trial will provide a novel combination of therapies, one being ONC201 and the other one Paxalisib and it offers this with standard of care, radiation therapy to try to increase the response of radiation,” Dr Dun said.

Surgery is usually not possible due to the location of DIPG tumour which are in the brain stem.

“The strength of this trial is the adaptive platform design, which allows us to constantly review emerging data, and rapidly incorporate new drugs without having to open a new clinical trial each time,” A/Prof McCowage said.

“Importantly, PNOC-022 is a global research effort, with researchers from all around the world – including Australia and New Zealand – coming together to put forward the most promising options to help these children.”

Alan Suy’s daughter Maddie, aged eight, is lucky enough get on the trial.

“Maddie is lucky enough to be accepted, she is one of the first, I’m feeling happy and fortunate, she is one of the first in Australia,” he said.

Mr Suy had travelled to USA last month trying to get his daughter on a trial.

‘If she couldn’t get on a trial here, I was going to enrol her over there,” Mr Suy said.

‘Our kids are dying’: Red tape blocks brain cancer drug trial

By Jane Hansen - 14/08/22

Desperate parents of children with terminal brain cancer are begging for them to be allowed onto a clinical trial of a new drug that offers hope – but is not approved for use in Australia.

The US is running a trial of the drug, called CBL0137, for the most deadly of paediatric brain cancers called diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma, or DIPG.

Children diagnosed are given just nine to 12 months to live and about 20 children a year die from DIPG.

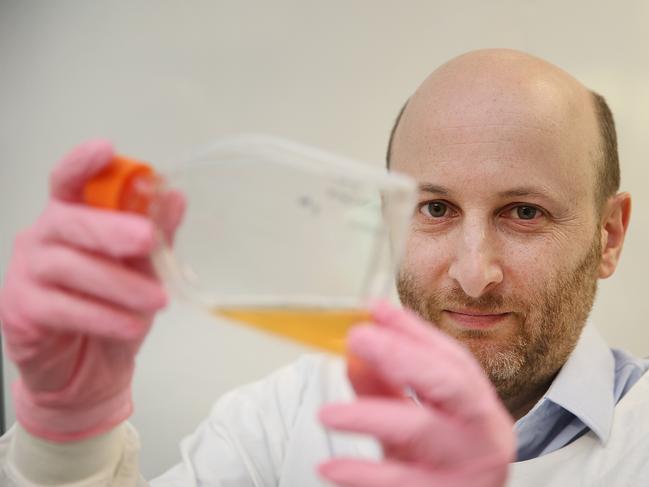

Sydney-based researcher David Ziegler is the principal investigator on the international trial but there is no start date for Australian children, some of whom have only months to live.

Angie Sari-Daher, whose six-year-old daughter Eve was diagnosed in March 2021, has started a petition to open these clinical trials to Australian families.

“Our kids are dying because they can’t access these trials or medications. We need to change this,” the petition reads.

Ms Sari-Daher, of Banksia, said: “The advice Australian families facing a DIPG diagnosis are given in relation to the CBL0137 trial’s opening date is ‘yet to be confirmed due to awaiting approval from the Ethics Committee’.

“No family should be told ‘go home and make memories’ without some hope at participating in clinical trials.”

Eve is on a different drug, which the family has accessed on compassionate grounds but is costing them $3000 per month.

This drug, ONC206, is from Germany and it, too, has not yet been approved for a trial in Australia.

Last year, Children’s Cancer Institute researchers announced that CBL0137 was effective against neuroblastoma and found it also interfered with the growth of DIPG tumours by inhibiting an important molecule.

“The finding that CBL0137 indirectly acts against this genetic driver is very exciting and gives us great hope for this treatment strategy,” Associate Professor Ziegler said at the time.

The trial is also part-funded by Australian charities and a National Health and Medical Research Council grant

“The oncologists mentioned to us at Eve’s diagnosis last year that (CBL0137) would be open in the next quarter but the date keeps changing,” Ms Sari-Daher said.

“They said the US FDA (Food and Drug Administration) approve things differently to Australia but I just don’t know.

“Research into this clinical trial was funded by different Australian charities and grants.

“Various organisations are contributing the much-needed funds for the research to take place but yet it is not available for us here to trial in our own country.”

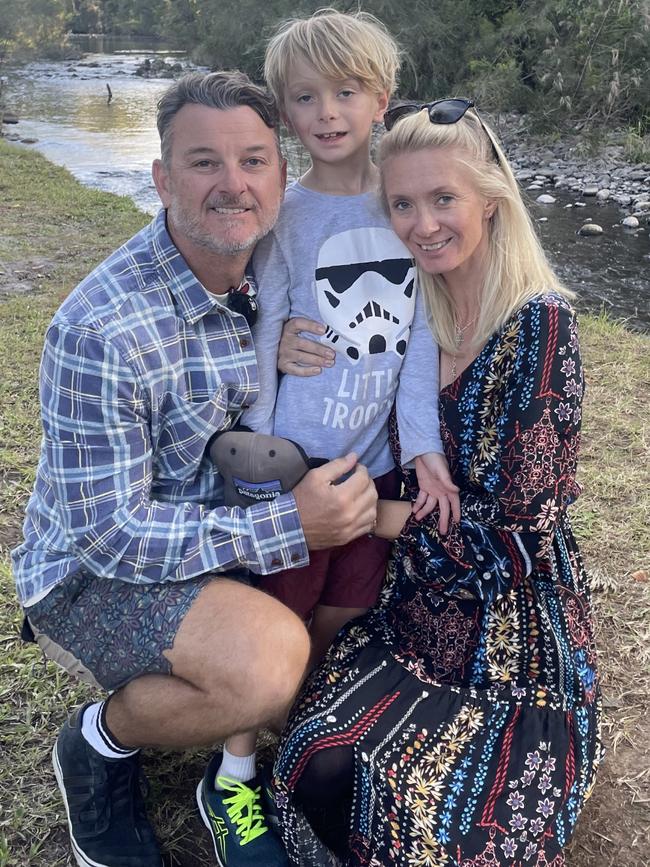

Alan Suy from Haberfield has spent the past two weeks in the US trying to get his eight-year-old daughter Maddie on one of many trials currently under way but he has been knocked back so far.

“There is limited options in Australia so we have been here in San Francisco for the last two weeks looking at all the possible options for trials,” he said.

“The challenge for a foreigner here is you have to fit the criteria and you’re competing with Americans to get on the trials, so we have had the door closed on us for some. Some are only available for local and not internationals.”

Huyen Tran’s daughter Zoe was diagnosed at two years of age and although she has defied the odds and will turn four soon, she is running out of time.

Her mum is desperate to get her on to the CBL0137 trial when it is approved.

“It is heartbreaking, the worst of the worst,” the Croydon Park mum said.

“I do everything I can do to extend Zoe’s survival time so that something comes along to give her a fighting chance.

“She is beating the odds, the average survival time is nine to 12 months.

“We have no information when the trial will come along, the oncologist said soon, but when is soon?

“It is really frustrating. With CBL0137 I believe Zoe is qualified but it is not open.”

Zoe deteriorated on Thursday and was admitted to hospital as she could no longer walk.

Beau Kemp from the Gold Coast is also desperate to get son Ryley on the CBL0137 trial. Ryley, 7, was diagnosed in January.

Through tears, Mrs Kemp said she had been knocked back by US facilities.

“In January, we were told Ryley was terminal and we had nine to 12 months,” she said. “I did make an appointment with Dr Ziegler and he went through the trials that are possibly going to open.

“We were told later this year, early next year … it’s so frustrating, we are just left on our own.

“I have reached out to American doctors, they are compassionate but they say it is not open to international.

“I don’t understand how we have one of the leading researchers in trials based out of Sydney and they have been open in America for some time but nothing here.

“We are coming on to the seven, eight months mark … three families I know lost their girls around the seven-month mark.

“His MRI he had in July shows it is growing, so it’s like a ticking time bomb. You just don’t know and all we get from the doctors is give him the best quality of life.”

The lack of progress on treatments for DIPG has forced desperate Australian parents to seek experimental treatments in Mexico.

Kathie and Adam Potts took their daughter Annabelle there for intra-arterial chemotherapy and immunotherapy in 2017-18, after she was diagnosed at age three.

Annabelle died, aged five, in January 2019.

“It’s absolutely appalling,” Ms Potts said.

“I’m shocked that charities and parents who have lost their children have been forced to fundraise to provide hope for children and provide that funding to Australian researchers for trials that aren’t even available for Australian children.

“It’s the red tape. We need to push these trials through, we need to rip up the red tape.

“These kids need hope, DIPG is a death sentence and it’s 20 kids a year who are dying.”