Operation Prospect: Bugging report shows NSW Police in crisis over ‘unlawful conduct’

THE future of Deputy Police Commissioner Cath Burn has been thrown into doubt by explosive findings that her conduct during a police bugging operation was “unlawful”.

NSW

Don't miss out on the headlines from NSW. Followed categories will be added to My News.

THE future of one of the state’s most senior police officers, Deputy Commissioner Cath Burn, has been thrown into doubt by explosive findings that her conduct during a police bugging operation was “unlawful” and “unreasonable”.

Ms Burn, who is also head of counter-terrorism, yesterday acknowledged that mistakes were made during her time as commander of the Special Crime Unit within the police internal affairs department unit when the bugging operation to catch corrupt police officers — called Operation Mascot — began in 1999.

NSW police’s Magnum Force — just like Dirty Harry

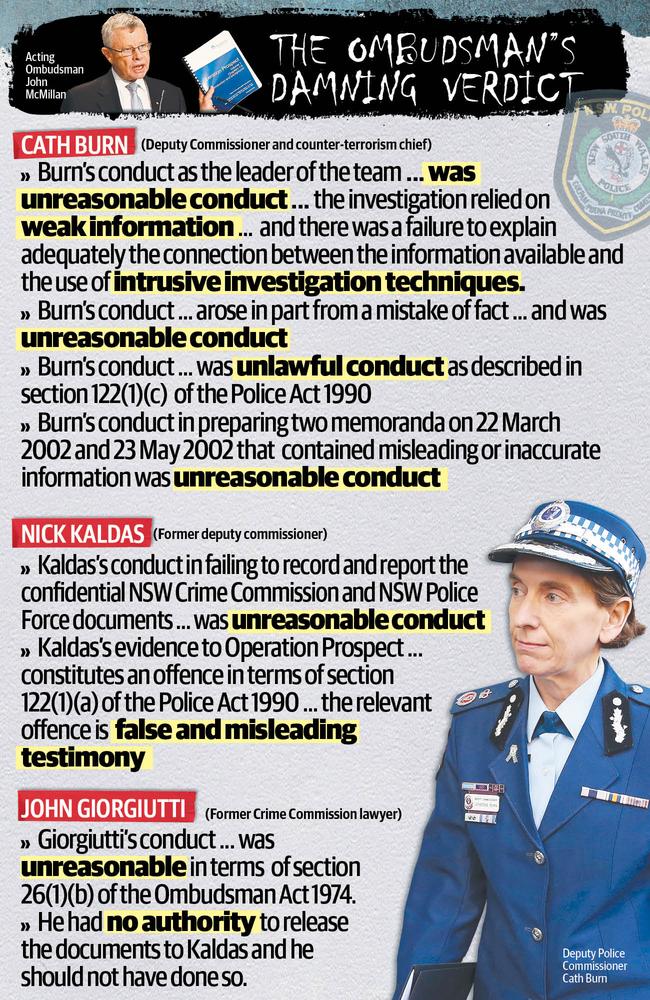

However, she rejected the four separate adverse findings in the so-called Operation Prospect report by acting NSW Ombudsman John McMillan, including that she had included “misleading or inaccurate” information in documents and allowed a police informant to breach bail.

With Police Commissioner Andrew Scipione due to retire in July, the state’s top female cop had been considered one of those in line to replace him.

But yesterday, acting Opposition Leader Michael Daley called on Premier Mike Baird and Police Minister Troy Grant to act to restore public confidence in the force.

The report into one of the NSW Police Force’s darkest episodes found “it was not uncommon that a person who was targeted for investigation by the Mascot Task Force would be named on multiple listening device and telephone interception warrants”.

“Some warrants named more than 100 people, and some people were named on close to 100 warrants,” it said.

Among them were dozens of innocent officers including Ms Burn’s former contender for the top job, Nick Kaldas, who retired as a deputy commissioner in April and now works for the United Nations.

The Ombudsman found that Mr Kaldas had at times acted improperly, including receiving information without complying with police conduct and failing to record confidential NSW Crime Commission and police documents relating to the bugging scandal which he had received anonymously.

The report, tabled in State Parliament, also made adverse findings against other former members of police internal affairs and the former head of the powerful NSW Crime Commission, Phillip Bradley.

But the most senior officer still serving from those days is Ms Burn, who was the leader of Mascot, which was a joint police, Crime Commission and Police Integrity Commission task force set up to investigate allegations made by a corrupt former police officer codenamed Sea.

He was used almost daily to secretly record conversations with fellow officers including 114 officers and a journalist at a leaving do, using listening device warrants which were found to have “defects and weaknesses” including stating allegations as facts.

The Ombudsman has not revealed who or how many serving or former officers have been referred to the Director of Public Prosecutions following the 16-year-old saga.

“The Mascot investigations achieved great success in uncovering police corruption and criminality,” Mr McMillan said yesterday.

“Yet many mistakes were made along the way, innocent people were unfairly named in warrants and affidavits … far too many names were drawn into the investigation based on hearsay and gossip.”

He found Ms Burn had prepared two memos in 2002 which “contained misleading or inaccurate information”.

RELATED NEWS

The purpose of the documents was to advise senior officers about the nature and status of serious allegations that had been made against police officers.

The Ombudsman, who has used code names for most of the bugged officers, found that Ms Burn’s conduct as the leader of the team that investigated Officer P through the use of listening devices and telephone intercepts and an integrity test was “unreasonable conduct”.

The term “unreasonable conduct” is clarified by the Ombudsman as “the issue is whether, viewed objectively, particular conduct was not based on reason or good sense, or displayed poor judgment in the circumstances”.

Ms Burn was also criticised for jointly implementing the investigation strategy to investigate Officer F based on allegations or statements that were either inaccurate or misrepresented when there should have been a more objective evaluation made.

Mr McMillan has recommended over a dozen officers receive apologies.

“While mistakes occurred at Mascot, I can say with complete confidence that, at all times, I performed my role conscientiously, ethically, honestly and in accordance with my oath of office, statement of values and the law,” Ms Burn said yesterday.

“The Ombudsman’s report includes several findings about the performance of my role while serving as the team leader of Mascot and for the record I reject these findings.”

Speaking from Jordan yesterday, a furious Mr Kaldas attacked the report, saying he had been denied procedural fairness and the investigation into the bugging had turned into an inquiry into those who blew the whistle on it.

“This investigation was meant to look into ... unlawful conduct — instead it turned into a witch hunt,” he said.

“Some of the comments and findings against me are simply factually incorrect, the result of careless, sloppy investigation.”

LEADERSHIP DEBACLE: HOW DID IT COME TO THIS?

Mark Morri Crime Editor

A SPECIAL crime unit inside the force’s internal affairs unit was so convinced of entrenched police corruption that it carried out integrity tests on its own officers and even had the police commissioner of the day, Englishman Peter Ryan, followed.

In 1999 the unit, known as SCIA, was set up on the fifth floor of the same Kent St building that housed the secretive NSW Crime Commission.

Members of the unit were told not to talk in the lifts because there were other police officers on other floors and no one could be trusted.

For the next three years the squad was relentless in its pursuit of corrupt police, believing there were hundreds of dirty cops all over Sydney.

Soon the whispers started, however, suggesting the units had become a law unto itself and was conducting illegal wire-taps and planting listening devices in people’s homes and offices.

Young officers started to talk about how people were being targeted because they were enemies of friends of the bosses or that they were overheard in a pub talking about how things were done in the old days.

Targeted officers such as Nick Kaldas complained to his superiors, and other officers did the same thing. Kaldas was openly despised by the unit’s chief, John Dolan.

Working under him was an ambitious officer called Cath Burn. The Police Commissioner Andrew Scipione also headed the unit in 2001.

Strike Force Emblems was set up to investigate the unit and Burn was interviewed a number of times about how SCIA targeted individuals.

The animosity between Dolan and Burn and Kaldas infected the police hierarchy for years. For nearly a decade Kaldas and others campaigned to have the findings of Emblems released but was stymied by the NSW Crime Commission and subsequent governments.

In 2012, the Ombudsman was ordered to investigate the unit and why the Emblems report had never been released.

A parliamentary inquiry found a number of police had been unfairly targeted, and yesterday the Ombudsman’s report was finally made public — damaging the reputations of Burn and Kaldas, plus many other officers.