Dark history behind the Sydney Royal Easter Show’s ‘Sideshow Alley’

Sideshow Alley has been an integral part of Sydney’s Easter Show for more than a century. But 100 years ago, there was a shadow side amid its sparkling attractions.

NSW

Don't miss out on the headlines from NSW. Followed categories will be added to My News.

“Step right inside” was the cry of the spruikers amid the sawdusted, spangled tents of the Sydney Royal Easter Show.

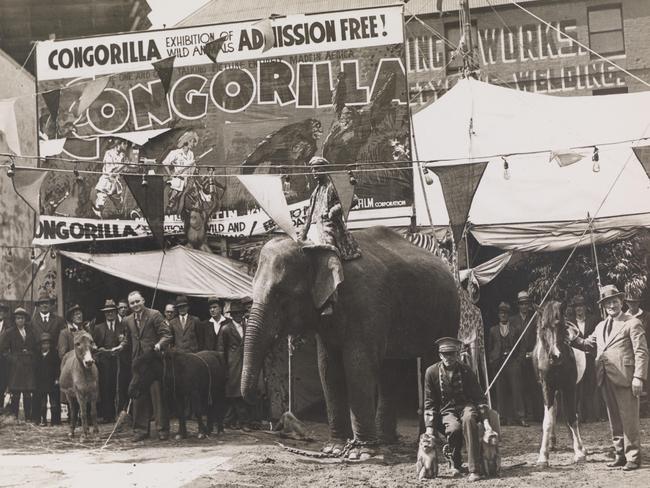

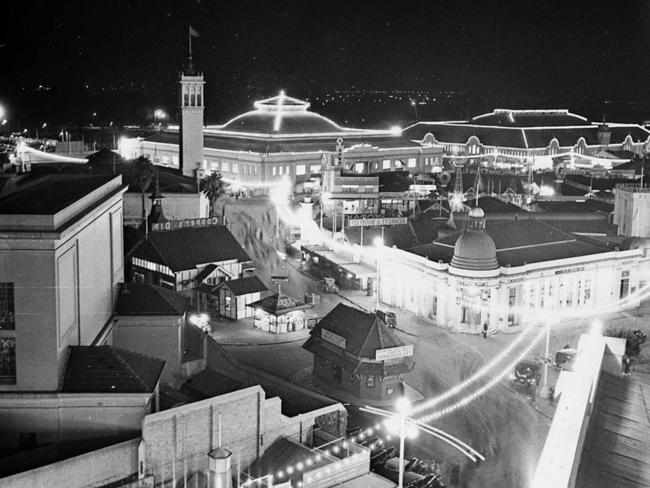

A century ago, the show’s Sideshow Alley was a strange and rowdy place where strong men, sword swallowers and snake charmers mingled among its tiny streets at Moore Park Showground.

The realm of carnival men and women who deftly extracted money from showgoers with their dark and mysterious arts, the popular show attraction was a gaudy world of rides, games, and illusions.

THE HEY DAY

Sideshows have been integral part of Sydney’s Royal Easter Show since the 1890s but it was the 1920s when they came into their own.

Back then, a motley crew populated the alleys from top-notch ‘showies’ and performers, to girly show spruikers and three-card grifters conning coins from the gullible.

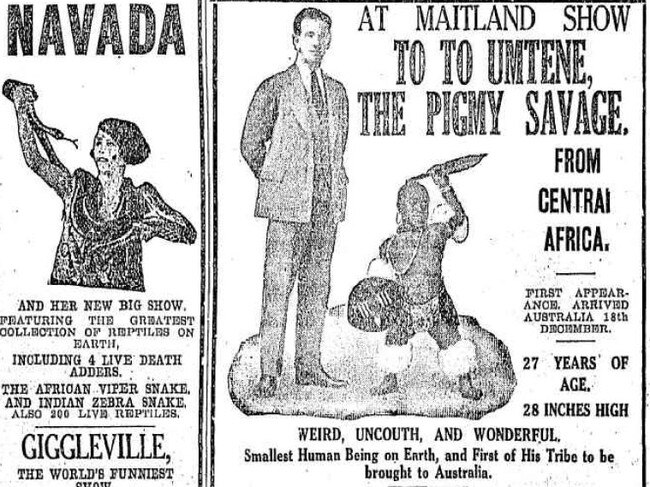

Sydneysiders could see all manner of wonders among the tents, including a 12ft woman (standing on the shoulders of a man in a very long dress) to the hypnotic Nevada the Snake Queen with her deadly collection of serpents, fangs intact.

By the 1930s, the alleys became louder and wilder, music blared, animals chattered and death-defying motorcycle stunts roared in the background. Attractions had grown bigger, brighter and better than ever before.

A WORLD TO ITSELF

Onlookers who poured into the showground’s alleys were met with sights both alluring and repulsive. The alleys themselves were pungent — human sweat mingled with the scent of kerosene torches, greasepaint and sawdust.

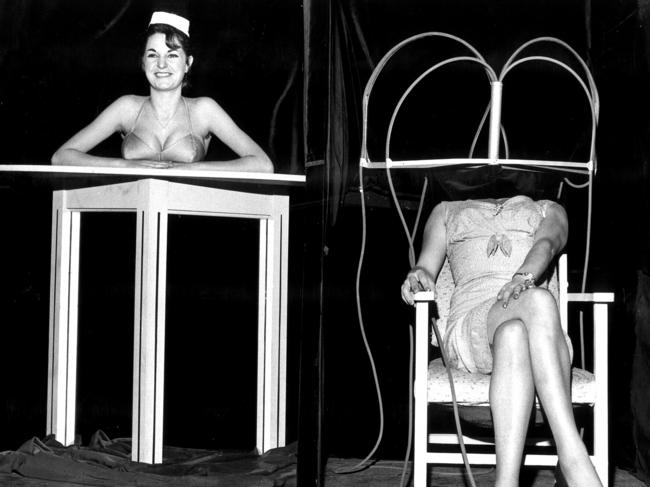

Within its confines, one could find Venetia with her half a tonne of snakes, or Tam Tam the Leopard Man preparing to run a sword through his female assistant, promising to restore her intact ahead of a feat of levitation and some black magic.

For five pounds, you could buy a kiss from a sturdy bush damsel and lose money on any number of semi-fraudulent ventures from fortune tellers to seers in sequined turbans.

BIGGEST, BRIGHTEST, BEST

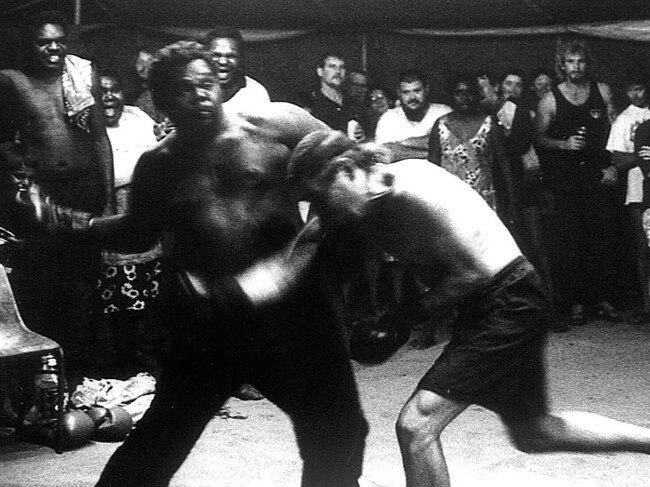

By the late 1930s, the ‘big shots” of Australia’s tent shows — Jimmy Sharman, Arthur Greenhalgh and Dave Meekin — were providing showgoers with a “phantasmagoria of sight and sound and excitement”.

The Sharman Troupe was an institution, with Jimmy Sharman’s trademark cry, “Who’ll take a glove?” ringing out among generations of customers who paid two bob to enter his big tent.

Greenhalgh and Jackson owned the mechanical rides, and wild west shows, along with waxworks, Chinese acrobats and magicians, jugglers and other attractions which flanked Jimmy Sharman’s boxing tents in the alleys at the show

Marjorie Van Camp’s was among their big drawcards, her Pig-A-Dilly Circus featuring pigs trained to fire guns and box in tiny rings, while the Globe Of Death delivered, fierce explosions of supercharged petrol, bursting back fires, cheering and applause.

“The three Hells — drivers in the globe of death — is one of the wildest and most terrifying shows that have ever been shown in Australia,” The Daily Telegraph reported in 1937.

Herb Durkin, Australia’s famous speedway rider, Frank Durkin, and Miss Noreen Durkin, pulled off incredible feats inside the globe, at amazing high speeds.

Dave Meekin, meanwhile, brought magic and mystery in the form of the famous Abdulla Brothers.

“In their black magic arts. Abdul amazes his audiences by lifting a 301b weight with his eyelids — a feat never before seen in Australia,” the Telegraph reported.

A MURKY WORLD

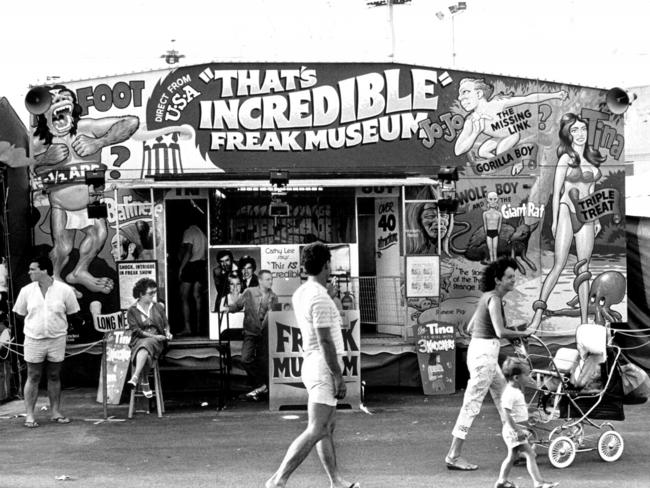

Among the sideshows was the shadow of human ‘freak shows’, where physical differences were considered a form of entertainment that could be exploited and profited from.

Queen Victoria’s endorsement of human “freak” shows had opened the doors for the shows to flourish and showmen including P.T. Barnum helped make them popular.

Maria Town, the president of the American Association of People with Disabilities, said in 2019, that such sideshows “set the stage for modern conceptions of disability … as inherently ‘other’ from mainstream society” and created the stereotypes the disability rights movement sought to resist.

Meekin was among the most famous ‘freak’ show promoters at the show, his performers including “Ubangi, the little Pygmy woman from the Congo … and Jang, the tailed boy, his greatest “scoop.”

A former boxer turned lion tamer, Meekin travelled extensively in Africa where he ’recruited’ Ubangi Chilliwingi, also known as ‘Maria Peters’, a Pygmy woman from Cape Province and the pair’s professional association led to the establishment of a Pygmy troupe that made them both wealthy.

While some performers were able to assert their worth and profit from the shows, others were severely exploited especially First Nations peoples.

In the 1880s and 1890s, Barnum formed the Australian Cannibal Boomerang Throwers after his agents ‘persuaded’ Aboriginal people to join his circus overseas.

Most would die from pneumonia, among them a man called ‘Tambo’ whose embalmed body was sold to a dime museum and only repatriated to Palm Island in 1993.

A NEW CHAPTER

By the 1940s, shows that held the human body up for ridicule or scrutiny were on the nose in Australia, as scientific and medical understanding of the body changed.

The Royal Agricultural Society in 1948 moved to lift the standards of sideshow alley, warning: “We shall also frown severely upon the type of public amusement which holds the human body up to ridicule. That means there will be no more bearded ladies.”

Exhibits of trained animals that had to be carried from town to town in close and often cruel captivity, whether fleas or lions were also out, as were snakes after three people were bitten during a snake-charming show the previous year.

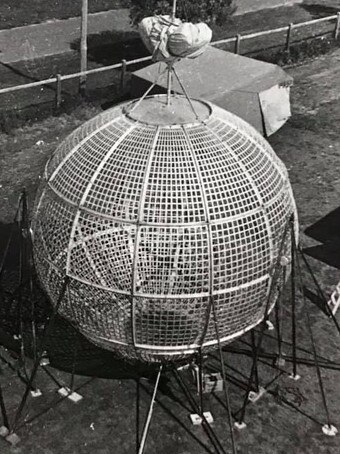

“Patrons are worthy of a better class of entertainment, and to secure it we are encouraging the introduction of more mechanical contrivances, such as miniature speedways, roundabouts, dodgems, a mirror maze, a ghost train, and a crazy cottage.”

STUNTS AND STADIUMS

In 1951, the daredevil Durkin family introduced the motorcycling Ring of Death and in coming decades, stunt acts and thrill rides eclipsed the attractions of the past.

By the late 1980s the show had outgrown its Moore Park facilities and in the late 1990s, it relocated to Sydney Olympic Park at Homebush.

Rides were now a huge part of sideshow alley, along with showbags, and more spectacular stadium entertainment.

Today, the show features more commercial and entertainment activities, however promoting and celebrating the state’s rural and agricultural industries remains its core purpose.

The show is Australia’s largest annual event, attracting close to 900,000 people each year.

The Sydney Royal Easter Show runs from April 1-12.