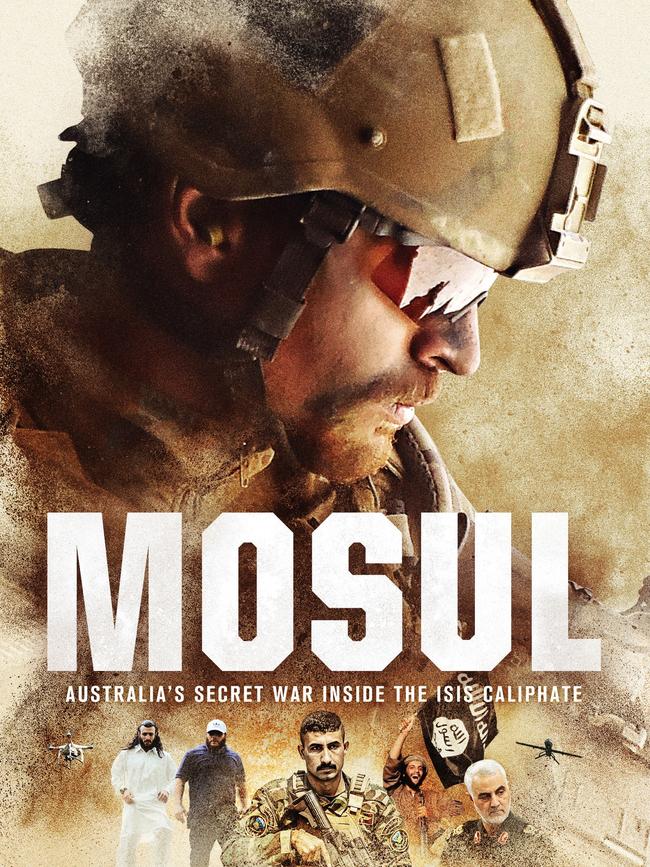

Mosul: Inside Australia’s secret war in the ISIS caliphate

Ben Mckelvey reveals the brutality faced by Australian special forces battling an increasingly desperate Islamic State as they became even more barbarous in their bloody last stand in Mosul. READ THE BOOK EXTRACT

NSW

Don't miss out on the headlines from NSW. Followed categories will be added to My News.

In his new book, Ben Mckelvey reveals the untold story of the battle for Mosul and the secret involvement of Australians on both sides of the war — as Commandos and ISIS fighters.

The following extract exposes the brutality faced by Australian special forces battling a desperate Islamic State during their last stand in Mosul.

After the fall of the Right Bank, the Australian and US special forces elements packed up their bases and followed the Iraqi commanders to a housing estate just south of Mosul proper.

As they had in Bartella, the commandos and SEALs commandeered large houses next to one another and replicated the facilities, strike cell and CPP that had existed to the east of the city.

This Tactical Assembly Area (TAA) became home for CTS commanders, as well as the American and Australian special forces, and with an Australian lieutenant colonel then in charge of coalition forces of that area, it fell to him to name the new base.

When US media was brought into the base to interview General Stephen Townsend, the US commander in charge of all coalition forces in the region, about the progress of the battle, the Australians disappeared as the cameras were rolling, but even so they left their mark for the keenest of observers.

The media from that visit posted and broadcast using the dateline: TAA Wyvern, named by Nathan Knox’s commanding officer after the mythical animal on the emblem of Australian Special Operations Command.

From TAA Wyvern the Australians watched as an increasingly desperate Islamic State became even more barbarous.

As they had in Ramadi, it seemed Islamic State was attempting to pull down every building they couldn’t hold in the western side of the city, and were indiscriminately killing Mosul’s remaining citizens while attributing those deaths and that destruction to the Iraqi Security Forces.

Buildings were rigged with explosives and detonated as the CTS approached. Often, when the CTS were engaging with ISIS and civilians were nearby, the ISIS fighters would shoot the civilians in the hope that the deaths would be blamed on the government soldiers.

Islamic State were also attempting to facilitate civilian deaths that would be attributed to the air campaign.

Nathan Knox describes an instance when the strike cell managed to see through an Islamic State effort to massacre civilians via a coalition air strike.

‘We saw these ISIS fighters on the top of a roof, with an ISIS flag and we’d be about to get a bomb on it and we’d be like, “Hold on, why the f**k hasn’t that dude moved in forty minutes?”’ Knox says.

The Australians called a CTS sniper to a position from which the roof could be seen, and through his scope the sniper saw a shop manikin, holding a cardboard AK-47.

When the CTS cleared through the building, they saw a chained door leading to a basement and, when it was opened, between 90 and 100 civilians came out.

‘They wanted us to bomb the place and then we’d get blamed for all these dead civilians.’

Knox says they weren’t always as lucky as they’d been in that instance, and a number of buildings were levelled with civilians trapped inside.

‘That really f**ked everyone up when stuff like that happened. I know it affected the pilots too.’

Knox says all of the Australians in country tried to be dispassionate about their work, but they were abhorred by Islamic State’s disregard for life, even their own.

It is not fair to say that hate was a motivating factor, but there certainly was a desire to see all of the Islamic State fighters in the city dead as quickly as possible, taking as few civilians or CTS fighters with them.

‘They weren’t going to be rehabilitated,’ says Knox of the ISIS fighters. ‘If they escaped, they were just going to do the same shit elsewhere.’

That’s why when Australian voices were heard over a dead Islamic State fighter’s radio, speaking about moving to a known madafa, the prospect of dropping a bomb on the madafa was a very desirable one for the Australian in the strike cell.

‘We could have really easily. There was never much going on at night, and we always had five or six planes flying overhead looking for targets. Would have loved to have pulled a house down on these pricks,’ says Knox.

Approval for such a strike would have been easy for the SEALs, but not the Australians.

They could have struck any madafa in the city, at almost any time with just in-room approval, but a madafa known to have Australian nationals in it was a different story.

Australian nationals could legally be killed in the course of the battle, which is to say their Australian citizenship was not a protective shield from the bombing, but targeting an Australian just because they were Australian was something that would have to be approved at a ministerial level, and likely a prime ministerial level.

Perhaps Tony Abbott, who was the prime minister when Mohammad Baryalei was killed, would have approved a strike on the madafa, but Malcolm Turnbull now had Australia’s top job and was possibly more reticent.

The men in the strike cell didn’t even need to ask approval for it to be rejected.

The Australian Signals Directorate was watching and listening to everything that was happening in the strike cell, and when the commandos discovered the Australian ISIS fighters, an ASD liaison working in Baghdad was dispatched to Mosul, with a stern reminder for the commandos that specifically targeting Australians in this battlespace in preference of other fighters’ targets would be a violation of Australian law.

The madafa wasn’t bombed that night, but it did eventually make its way onto the target list. When it was bombed it may or may not have been hosting Australian jihadi.

By the beginning of March, the Islamic State occupying forces in western Mosul were largely cut off and isolated.

With the help of the strike cell, Iraqi forces had taken the western part of Iraqi Highway 1, which leads out of the country toward Syria, and a section of the Tigris nearby, cutting off Islamic State’s potential paths of retreat.

Occupied villages west of Mosul and the smaller occupied city of Tal Afar were attacked by the PMF. Defeat beckoned in Mosul and also an impossible retreat.

‘We started seeing ISIS guys trying to mix in with the IDPs who were fleeing the city,’ says Knox. ‘We started thinking, “Shit, man, maybe we’re going to see this thing through [before rotating out].’

Over the first three days in March, a storm rolled over Mosul, and with high winds and low cloud making aerial surveillance and attack difficult, Islamic State fighters let an estimated 14,000 civilians escape from Islamic State – occupied territory.

A number of ISIS fighters mixed in with the group, not to escape, but attack. When the fighters were close to the CTS position, they opened fire, in a rare, concerted counter-attack. The attack was thwarted, but not before dozens of the fleeing civilians were killed.

During the same rainstorm, Islamic State indiscriminately fired mortars, some with an explosive payload, some with a chemical, into the eastern side of the city in what seemed to be a purely punitive and random attack.

These random attacks would continue until the liberation of the city.

This is an edited extract from Mosul — Australia’s secret war inside the ISIS caliphate, by Ben Mckelvey. Published by Hachette Australia, RRP $34.99