Miranda Devine: What’s driving Bill Shorten’s quest to be PM?

The man we first met at Beaconsfield has taken a complicated political — and personal — approach in his quest to become Australia’s next prime minister.

As Scott Morrison closes in on Bill Shorten like the proverbial tortoise to the hare, angst is rising in the Opposition Leader’s camp.

But if today’s polls, pundits and punters are correct, this weekend Australia will hand power to Shorten, a man we barely know.

Despite his six years as Labor leader, Shorten, 52, remains opaque, and his friends say this is by design. Some barely recognise the man they used to know.

They say Shorten is the last of the Labor Right leaders, but he has subsumed any core beliefs at the helm of a party that has moved drastically, unrecognisably, to the Left since the halcyon days of Hawke and Keating.

“I look at the campaign and his policies and I don’t recognise the Bill I knew,” says a friend from university days.

“He has had to make all these trade-offs to keep Albo (left faction rival Anthony Albanese) and Tanya (Plibersek, his left faction deputy) at bay. Just like Malcolm Turnbull.”

MORE NEWS:

Aussie tourist killed in seaplane crash named

Man lunged at cops with knife before being shot in stomach

DUI driver who had disabled child in car avoids jail

If he wins the election on Saturday, “he’s going to have to reveal himself. People don’t know what makes him tick … He’s been hiding all this time.”

Polls show Shorten to be deeply unpopular now.

But we first met a very different, and very likeable Shorten in 2006, at the Anzac Day mining disaster in Beaconsfield, Tasmania, when he became the human face of the union movement after an earthquake trapped three goldminers underground.

Larry Knight, 44, was killed, but Brant Webb, 37, and Todd Russell, 34, were trapped alive in a confined space underground for two weeks as the nation hoped and prayed for their survival.

Shorten, boyishly handsome in branded bomber jacket, was the 38-year-old National Secretary of the Australian Workers’ Union, fronting up to the media several times a day for updates for 14 days straight.

The diminutive, Jesuit-educated lawyer with an MBA was the calm, ever-present voice who made us believe everything that could be done for the miners would be done, that rugged Australian derring-do would win the day. And so it proved.

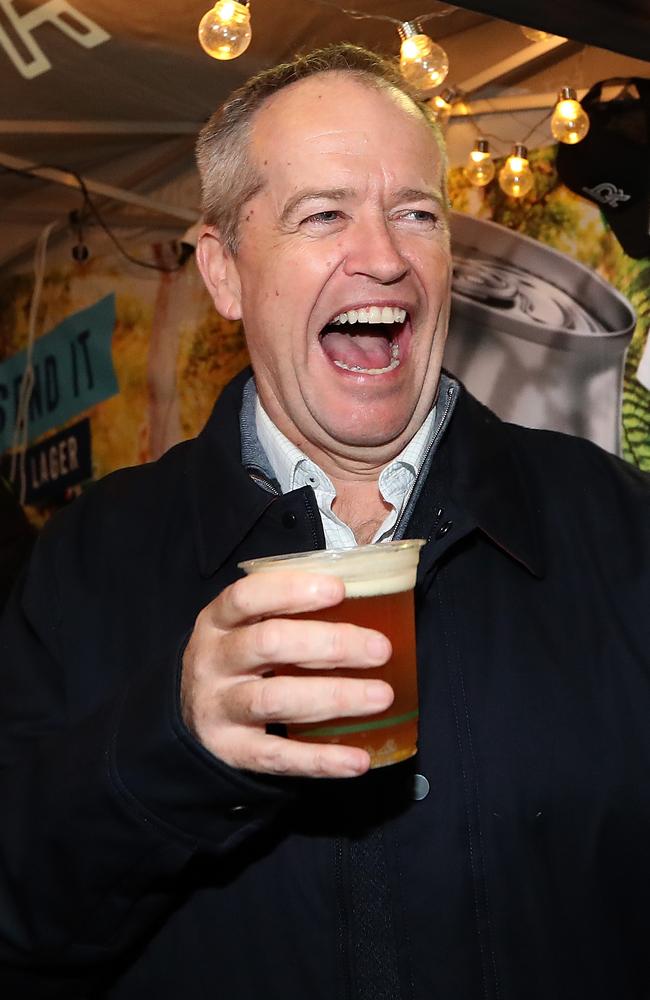

Webb and Russell became the miracle survivors and Shorten made sure he was filmed alongside them at the Beaconsfield pub after they walked free, raising a beer to his lips perhaps a bit too ostentatiously for Channel 9’s cameras.

It was Shorten’s finest moment, and softened the image of the unions. It also happened to catapult him onto the national stage just in time to fulfil what he believed was his political destiny, to be prime minister.

There was no sign, behind the genial “aw shucks” manner, of the ruthless political killer who had only a year earlier snatched preselection for the seat of Maribyrnong in Melbourne’s inner-west from incumbent MP Bob Sercombe in a cross-factional fix.

Shorten somehow secured the support of the hard left unions, a debt that hovers to this day.

NOT THE MESSIAH

Left with no choice but to step aside, Sercombe said of Shorten: “He’s not the messiah … He’s just a naughty right-wing boy.”

There was no sign either then of the fork-tongued union leader who had negotiated enterprise agreements which sold out his workers’ pay and conditions in return for unusual payments to the AWU.

The Cleanevent cleaners and Chiquita Mushrooms pickers were silent then about the forgone wages which had filled the coffers of Shorten’s union and helped propel his glittering career.

There was, however, a sign of his efforts to disguise his privileged education with what old friends say was an acquired speech affectation in which he substitutes the sound “v” for “th” so that the word “with” becomes “wiv”.

This speech peculiarity waxes and wanes depending on who Shorten is talking to, but one acquaintance says it served as a mark of the working class among unionists who regarded his posh schooling as suspect.

Shorten’s detractors dubbed him “Showbag Shorten” and grumbled that he had capitalised on the miners’ plight to boost his political fortunes.

But there seemed to be a refreshing authenticity to this articulate new-age union boss.

He even revealed a little of his world view when he spoke of how the trapped men had remained strong: “Having met their families I do realise the power of family and their support. The wives love their husbands. I think that’s important to their wellbeing. Great kids, great parents. You get a sense, I think, that your family helps make you who you are.”

Shorten grew up with his non-identical twin brother Robert in working-class outer-suburban Melbourne.

His late father, also Bill (William Robert, from whom both sons take their names) was a Geordie migrant from Tyneside in the UK, a wharfie and loyal union man, who, under the firm guidance of an ambitious wife, rose to dock master at the Duke and Orr Dry Dock in South Melbourne.

Ann Shorten was a schoolteacher, descended from the Irish McGraths, O’Sheas and Nolans who came to Australia in 1853 to discover gold.

They were very different people. Ann was a clever, driven, upwardly mobile “cultural Catholic” intellectual with aspirations for herself and her sons, while Bill Sr, a heavy smoker and drinker who spent a lot of time at the pub with mates, was said to have the chip on both shoulders commonly found at the bottom of the historically rigid British class system.

Friends say he made sure his sons didn’t get ideas above their station, despite attending one of the most prestigious schools in the country, at their mothers’ insistence.

Shorten’s parents eventually split up when he was at university, and Bill Sr remarried, leading to an estrangement with his son that lasted almost to his death.

TROUBLED WATERS

The subterranean power struggle in his parents’ marriage, so familiar to children of the second-wave feminism 1970s, probably set up the psychic duality sometimes evident today in Shorten, who looks like his father, and followed him into the union movement, but was devoted to

his mother.

Shorten described his late parents’ often fractious relationship in his 2016 autobiography For the Common Good: Reflections on Australia’s Future.

“(Mum) met my father while on a holiday cruise to Guam in 1965. Dad was working as an engineer on the ship. His family also had a long history of union involvement at the Newcastle (UK) shipyards …

“Mum always said Dad was an intelligent man.

“When he came ashore and married Mum, she made him get his chief engineer’s certificate. He was street smart and possessed good people skills but ended up taking refuge in the drink like many men of his generation.

“Looking back, Dad was probably depressed, but they didn’t have counselling then … Dad was an old-fashioned father — he grew up during the Depression after all. I can’t pretend there wasn’t conflict at home. Dad was never physically violent towards Mum, but there were plenty of arguments and, looking back, I can see that a permanent undercurrent of tension persisted in our home life …

“When I was 10, the same age he was when his father died, Dad suffered a heart attack. It hurt seeing that. No child should ever have to see their father so vulnerable at that age. Yet it changed him. He stopped drinking as much, which was welcome, although he developed a shorter fuse.”

At school, Shorten’s twin, Robert, was taller, handsomer, sportier, quieter, more interested in maths and science and luckier with the ladies.

They both went on to study law at Monash and Robert became an investment banker in Sydney. The brothers are said to be close.

Shorten, who was a boyhood fan of Winston Churchill and devoured history books by Manning Clark and Charles Bean, preferred drama and the humanities.

He won several academic prizes at school and won a place on the state debating team.

Bob Hawke’s election when he was 15 ignited his political ambition.

Their mother worked full-time so the family could afford to put Bill and Robert through Melbourne’s prestigious Jesuit Xavier College.

His tearful over-reaction last week to The Daily Telegraph’s fleshing out his depiction of his upbringing as underprivileged was in part a son’s instinctive defence of a beloved mother, who died five years ago.

Shorten told the ABC’s Q&A that his mother, who died in 2014, had been forced to take a teacher’s scholarship because her family couldn’t afford for her to follow her dream of becoming a lawyer, not have the money to go to university.

He omitted to explain until his emotional press conference, that she enrolled in law in her late 40s, “topped the law school” and became a barrister.

But “she got about nine briefs in her time. It was actually a bit dispiriting … She discovered in her mid-50s that sometimes, you’re just too old, and you shouldn’t be too old, but she discovered the discrimination against older women.”

One friend, watching the tearful performance, said: “It’s the most authentic he’s been for years”.

Shorten’s first marriage was to stockbroker and blue blood Liberal Debbie Beale (now chair of Melbourne’s Federation Square), whom he met in 1999 while they were both studying for their MBAs. They were engaged two weeks after they first met.

Through Debbie’s wealthy father former Liberal politician Julian Beale, Shorten was embraced by the Melbourne establishment, the so-called “top end of town” that he now reviles.

TRUFFLES AND BUBBLES

He is said to retain his fondness for the high life, with acquaintances noting he relishes the truffle chips and sparkling wine of the Virgin lounge.

But less than a year after he entered parliament, the “power couple” split in circumstances that have never been explained.

He reportedly blindsided Beale at an AFL match in 2008, telling her the eight-year marriage was over.

A month later news broke of his relationship with Chloe Bryce, the daughter of former governor-general Dame Quentin Bryce.

Chloe, then 37, was going through a divorce from husband Roger Parkin, an architect 23 years her senior, with whom she had two small children.

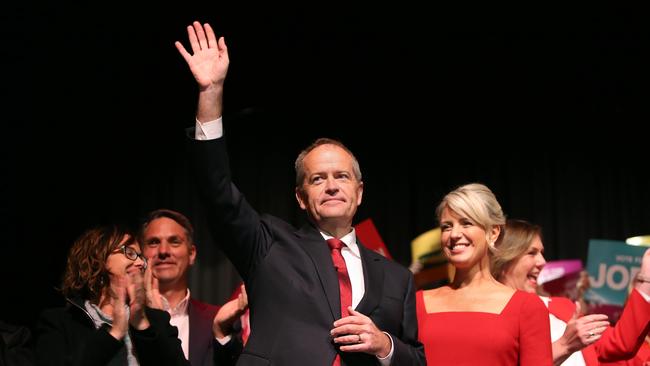

Now the second Mrs Shorten, a photogenic presence on the campaign trail, Chloe has previously said she first met Bill when he was at the AWU.

But whatever questions there may have been about the timing of the relationship, the details remain private.

Debbie Beale has been loyally silent about the breakdown of her marriage and friends praise Shorten’s devotion to Chloe’s children, who he took on as his own.

By all accounts, Rupert, 17, and Gigi, 16, adore him. The couple went on to have a daughter together, Clementine, 9, who his staff describe as “really clever, a mini-Bill”.

Back in his Beaconsfield moment, when Shorten the union boss was first mooted as a future Labor leader, polls put him well behind Julia Gillard and Kevin Rudd, who just months later would seize the leadership from Kim Beazley.

The following year, Rudd became PM, Gillard his deputy and Shorten was just another ex-unionist on the backbench who had ridden into government on Rudd’s coat-tails.

Incredible that by the Abbott landslide of 2013, Shorten had clawed his way to the top of Labor, betraying both Rudd and Gillard and setting off a decade of regicide that has convulsed both major parties.

And now he stands on the brink of achieving his childhood dream.