Military heroes in fight of their lives as more veterans die through suicide

Too many of our combat veterans are taking their own lives. One ex-serviceman thinks he knows what’s behind this worrying trend.

I woke up with a panic, almost a scream inside my head, or was it screaming, the terror was there.

I couldn’t place myself, I knew I was in a dark room but unable to pinpoint how many people were there or why I was so terrified, I tried to remember, I saw a face, an unfamiliar

face full of panic but then it was gone,

the memories were fading. — RAN Petty Officer Dave Stafford Finney, June 2018.

Royal Australian Navy Petty Officer and marine technician Dave Finney, 38, wrote those words just seven months before he killed himself. He had woken up in bed at home, “swimming in sweat”, his jaw clenched so tightly it was cramping. He guessed the “dark room” was a ship. Then his wife looked at him and “seemed to just know, she didn’t need to ask”.

As Dave, a father, showered he tried to recall what exactly the nightmare was about. He stood in the shower, with an almost “vacant” mind, not washing but just standing — “knowing that the feeling, that I could now barely recognise, would be there for hours, maybe the day, maybe longer”. In his mind’s eye he thought of his decorated service for the country — places like Bougainville, East Timor, Darwin.

“I ran through moments on the boat and then I realised my mistake, I felt instantly like something terrible was about to happen or had happened, I couldn’t tell. It was like a mixture of panic and anger, a boiling pot of emotions, the easiest thing to do at that point is vent, I want to scream and put my fist through the shower door, but it didn’t fit.”

He battled through the day, took medication and ended up going to hospital multiple times during 2018. Diagnosed with post traumatic stress disorder, he needed help from the agency responsible for caring for ex-soldiers, sailors and air force personnel, the Department of Veterans’ Affairs.

In October last year he asked for help in finding a psychiatrist. He received a blunt email from DVA’s outsourced agency social worker saying he might have to wait until April 2019 because of lengthy waiting lists.

Fighting government agencies for help amid a mind-boggling level of red-tape has been an all-too-common complaint made by veterans across the country.

Dave Finney died on February 1 this year and his Adelaide-based mother Julie-Ann Finney has bravely spoken out publicly about his case in her effort to get a royal commission called. She wants to give a voice to the dead.

“We need to hear the voices of those who have passed,” she says. “That can only happen through their families … We don’t need academics, the Australian Defence Force, the Department of Veterans’ Affairs and the government deciding what will work.

“They have been trying that for years and it is not working. They’ve had enough chances.

“If I wasn’t making a noise, my son would be buried and they would have moved on.”

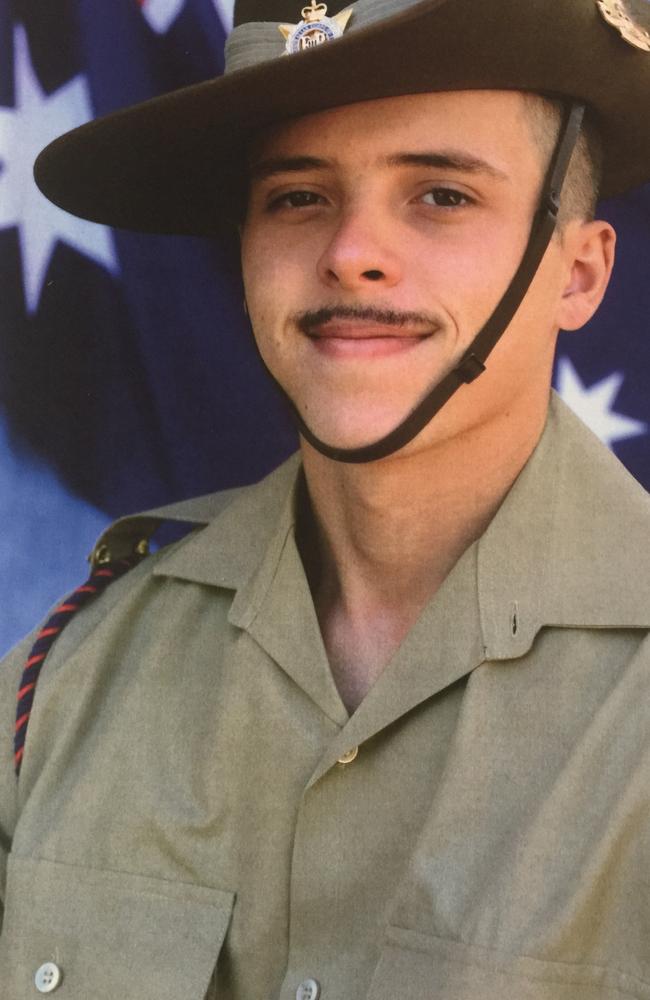

Sydney marketing expert Michelle Zamora’s brother, RAN Petty Officer Dan Herps, died in 2014 after losing a battle with PTSD.

He had served his country since the age of 17, when he joined the navy, going to the Middle East, as well as in defence intelligence and on border patrol near Christmas Island, where he saw children die. He, like Dave Finney, wrote about his mental health struggles in his own journal, saying he admitted himself to hospital after having panic attacks.

“I was having suicidal … ideations and felt like life was out of control,” he wrote.

“All the traumas I had hidden away were rushing back at once and in full force and were overloading my senses. So I live in the real world but also have so much displacement of traumatic events that I feel I am in two places at once.”

Ms Zamora backs calls for a royal commission and wants to meet PM Scott Morrison face-to-face so he can hear directly from the families.

“I knew my brother was troubled,” she says. “But it was only in the last year of his life, I knew the struggles to have a name — PTSD.

“When he stayed at my home he would wake in the middle of the night with terrors and then pace the house for hours until we all awoke.”

The problem of military suicides — which in numbers of dead outstrips recent battlefield injuries — is not new.

Studies show relative risks for “suicidal ideation” among veterans are 7.9 per cent higher than the Australian population, and 9.7 per cent higher for planning one and 13.8 per cent for attempts.

Servicemen under 30 have a suicide rate 2.2 times that of their non-military peers. In 2017, an astonishing 86 died by their own hand, and 80 during 2016, more than one a week. It dropped to 48 last year and is believed to have reached 14 this year.

Grieving families have called for a royal commission for many years now, but so far this has fallen on deaf ears.

In 2009, a government-ordered review into the problem by public health specialist Professor David Dunt said that new recruits undertook forcible “psychic reorientation” when they began training.

And if they fail to succeed, and are discharged on medical or other grounds, that can set in train a sequence of negative reactions such as anger and resentment. He also highlighted the complexity for veterans of dealing with three different military compensation schemes.

The Rudd government accepted his findings and gave $9.4 million over four years to implement the recommendations, which included plans to “enhance the mental health workforce” and improve training through stress management programs.

But veterans and families say the problem didn’t go away and after sustained pressure, a federal senate inquiry, The Constant Battle: Suicide by Veterans, was called. It shone a spotlight into an appallingly cumbersome bureaucracy and the difficulty of navigating multiple pieces of legislation, where veterans must use “advocates” to deal with claims, tribunals and reviews.

This 2017 inquiry’s findings in turn led the PM to order a Productivity Commission review, which is handing the final report to him within days.

But the original senate inquiry’s findings appeared to have underestimated the suicide problem. Relying on figures from Defence, it stated that between 2000 and September 2016, 118 full-time serving ADF members were suspected or confirmed to have died by suicide and 83 ex-servicemen and women had died in the 10 years before 2015.

DVA conceded its figures were incomplete because it only finds out about the death if a dependent puts in a claim for compo or income support.

But late last year a new analysis of the figures by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), put the death toll between 2001 and 2016 at 373. That includes serving, ex-serving and reserve personnel.

And it appears that is also an underestimate.

Veteran Scott Harris, from the support group The Warrior’s Return Facebook page, says the figure is more likely to be 412 for that time period.

He’s meticulously researching and recording current military, and veterans’, suicides dating back to before the Boer War of the late 1880s. He says the AIHW figures do not include someone who served before 2001 but died at their own hand after that date, in 2005, for example. And he has made some startling discoveries during his four years of research of historical records at the Australian War Memorial, police and defence records, and notifications from the general public. Each case he crosschecks with families, death certificates and coronial inquests.

“The suicides go in waves after every conflict,” he says. “You can see it on a graph after the Boer War, World War I, II and so on,” he says. “I knew it would be bad when I started out but I didn’t know it would be this bad.”

His figures show that there were no deaths during the 1880s, until you reach the Boer War in 1889, and there are two deaths. During the years before WWI, the suicides were in single figures, and in the early 1910s, there were none.

Suddenly, in 1914 (when the war began), the figure rises to 13, then leapt up to 133 in 1915 and 125 in 1916.

During the 1920s, the numbers go down and the decade total is 90. Between 1931 and 1940 Mr Harris records 70.

Then, with WWII, the figure jumps again to 488 for the decade of the 1940s.

During the 1950s it drops to 42 for the decade. Then in the ’60s, encompassing Vietnam, it rises to 226.

During the 1980s it drops to 135, then steadily climbs again as Australia undertook peacekeeping missions and conflicts in the Middle East. For the period from 2011 to 2018 the figure hit 385 based on Mr Harris’ calculations.

Mr Harris, a former sergeant in the Australian Army, believes Defence — and society generally — needs to work to stop it being a “taboo subject”.

“We need to talk about it, if someone needs assistance, stand up, don’t turn your back on them. If you can’t help them, find someone who can.”

Nikki Jamieson, whose 21-year-old soldier son Daniel Garforth took his life in 2014, has gone on to become an expert in the subject. She did a Master’s in Suicidology and is now doing a PhD in veteran suicide and has become an advocate. She’s at the forefront of a new theory that has emerged during the mid-2000s, called “moral injury”, to understand one of the dynamics behind military suicides.

It manifests when individuals’ moral codes are violated and they become distressed at watching unjust or immoral behaviour or betrayals — to themselves and others.

“Moral injury can happen by witnessing an act, or perpetrating an act that violates your moral codes and values,” she said. “Or it can happen when we are deeply betrayed (for example) by leadership decisions especially if they result in injury or death.”

She says it’s not PTSD, but veterans could be suffering from both. “Moral injury can manifest as shame, guilt, intense grief, self-condemning behaviours and ultimately leading to a loss of identity, friends … a loss of purpose than can lead to a loss of a reason to live.”

She says the recruits are given 12 weeks of intense training when they sign up — yet only one day of optional “transition” leave when they wind up.

“Defence should spend 12 weeks building them up again, at the very minimum, how to adjust to civilian life and how to build their support networks, how to deal with having their moral codes broken.”

Lifeline: 13 11 14