The Trocadero, Fort Macquarie, The Natatorium and other once-famous landmarks lost to time

FROM underground pools to rancid burial grounds, huge department stores and even a fort, these images show how much the city has changed in 200 years.

NSW

Don't miss out on the headlines from NSW. Followed categories will be added to My News.

THEY are the buildings that time forgot, former landmarks once patronised by thousands of Sydneysiders now replaced by high-rise office blocks and other developments.

From sprawling department stores with 52ha of lavish retail space to inner city forts and Art Deco dance halls, we revisit some of Sydney’s buildings now lost to the past.

Do you have a cherished memory of a lost landmark? Tell us in the comments section below.

THE NATATORIUM AND PEOPLE’S PALACE

Opened in 1888, the Natatorium Hotel at 400-408 Pitt St featured the city’s first non-tidal pools in its basement. Filled with salt water pumped from the harbour almost two miles away, the two amazing indoor pools became the heart of Sydney’s swimming fraternity.

Built by the Sydney Bathing Company as part of a five-storey 94-room hotel, the hotel itself was unprofitable, and the building was taken over in 1899 by the Salvation Army.

Converted into the People’s Palace with ‘doss’ rooms, a dorm for boys and a better class of accommodation for the more industrious, the palace soon grew to accommodate 600 souls. By the late 1920s there was strife as thefts, fisticuffs even murder plagued the palace, which had become a “Citadel of Deliverance” for the unruly and intoxicated.

By the 1980s, the Salvos sold the People’s Palace, then named the Pacific Coast Budget Accommodation. Today all that remains is part of the facade.

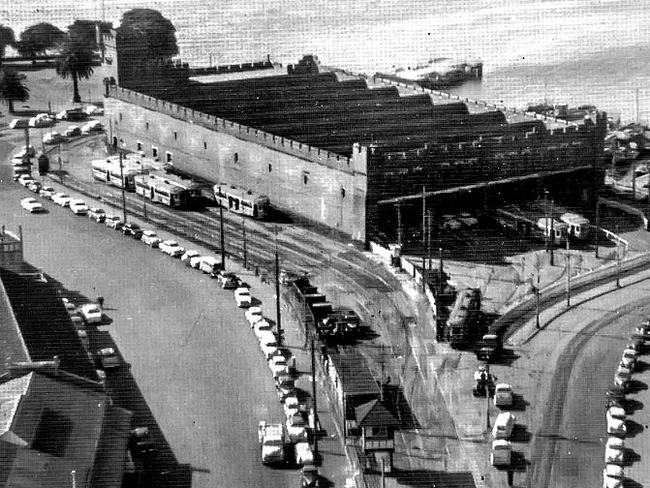

FORT MACQUARIE

Dating back to the days of Lachlan Macquarie, the square castellated battlement fort was the old colony’s most conspicuous landmark.

Built at Bennelong Point between 1817-1819 on an isolated reef, it was separated from the mainland by a channel of water with a draw bridge providing entry.

Fifteen guns were mounted to defend Sydney Cove, a two-storey tower stood in the centre of the fort and a powder magazine capable of storing 350 barrels of gunpowder was built underneath.

The tower could accommodate a small military attachment — one officer and 18 men, with stores for the battery.

In 1901, the fort was knocked down and converted into a tram depot which was in turn demolished in 1958 to make way for the Sydney Opera House.

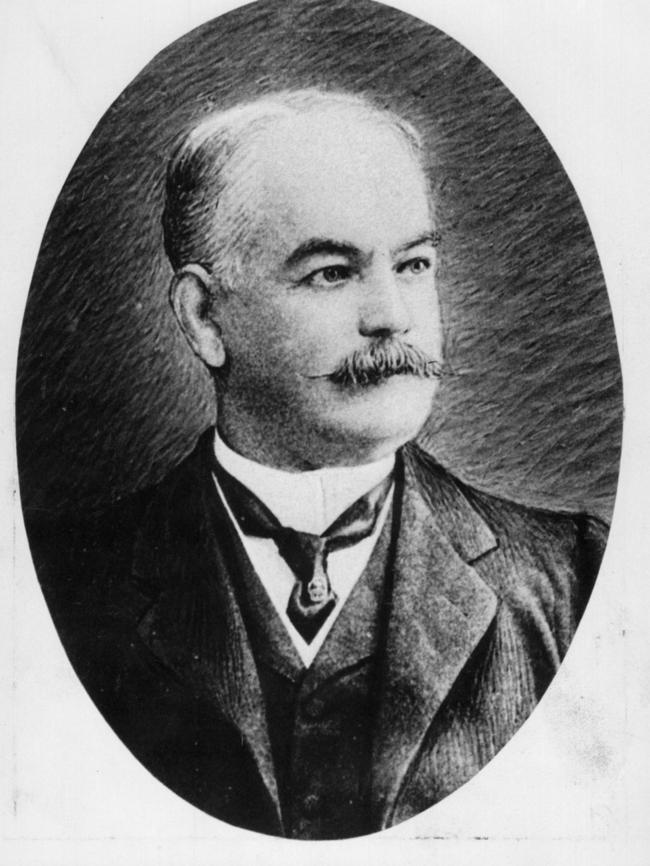

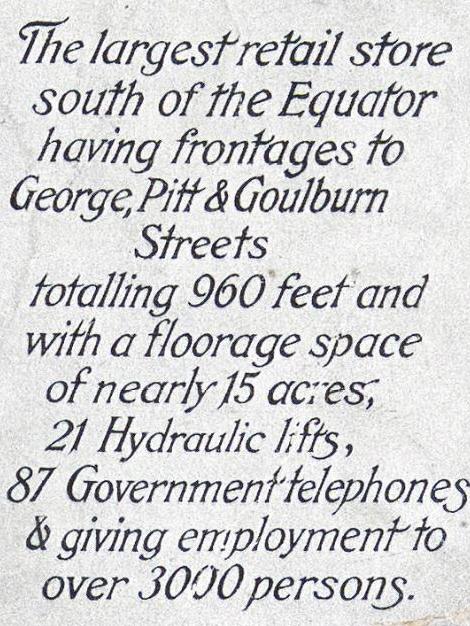

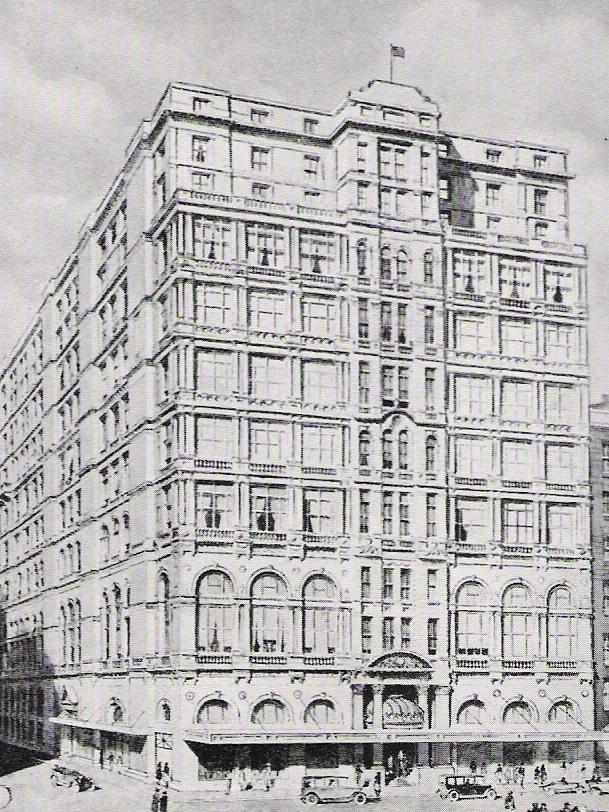

ANTHONY HORDERN’S NEW PALACE EMPORIUM

Built in 1905 and described as the “embodiment of fairyland” by a 1907 news report, the mammoth Victorian department store was a counterweight to the QVB up the road.

Lauded as a marvel of Australian architecture, the drapery business started in 1823 by English immigrant Anthony Hordern was by 1905, under son Samuel Hordern, a six-storey emporium occupying an entire city block.

Bounded by George, Goulburn, Pitt and Liverpool streets, the store featured 52ha of lavish retailing space and was a hub of social activity in the southern CBD.

On its 50th anniversary, Hordern’s gave away 50,000 oak seedlings imported from England, many which still survive in Sydney including one at The Oaks Hotel in Cremorne.

However as malls sprung up in the suburbs, business began to stall and Hordern’s closed in 1969. It was taken over by Waltons and demolished in the early 1980s for the World Square.

THE OLD KENT BREWERY BROADWAY

Established by Tooth & Co in 1835, generations of families worked at the Chippendale brewery opposite UTS, with 1000 people still employed in the 1980s.

Likened to a “city within a city” after 1870s Lord Mayor Allen Taylor levelled the surrounding slum houses to make way for factories, business was booming by the 1930s as the brewery scored lucrative deals including supplying the army.

But by the 1950s and 60s, the company was dogged with problems with a shortage of building materials, brewing ingredients and antiquated equipment.

Prior to 1980 there were 1000 personnel at the brewery before a large redevelopment saw all but one of the original buildings demolished.

Carlton and Uniting Breweries bought what was left but rumours of the brewery’s demise were a constant source of stress for workers, despite a generous three-schooner-a-day allowance.

The brewery closed in 2005 and the site was bought by Frasers in 2007. It is now part of the Central Park redevelopment.

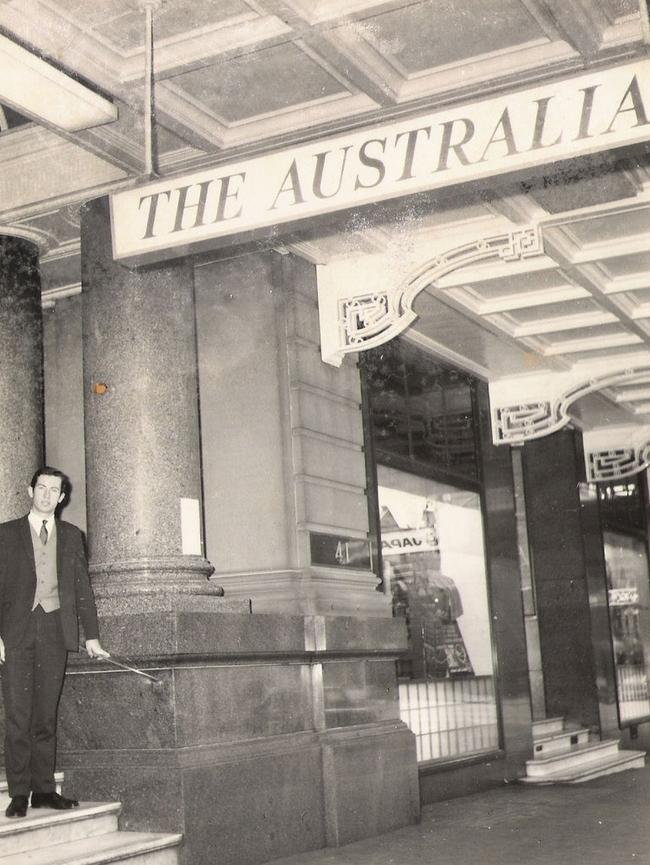

THE AUSTRALIA HOTEL

Opened in 1889, the Australia Hotel in Castlereagh St near Martin Place was the premier hotel in Sydney and quite the place to make an entrance.

Through its polished granite foyer, guests climbed the magnificent neo-classical staircase which led to the first floor decked out in Carrara marble before tackling the mahogany Victorian grand staircase to their rooms.

The ten-storey establishment was the place to be seen in high society and its illustrious guests included Marlene Dietrich and Robert Helpmann.

But it wasn’t to last and in the late 1960s, the Australia was sold off to MLC Insurance, which quickly shut it down in 1971 and demolished it to build a 68-storey office block, now the MLC Centre at 19 Martin Place.

THE TROCADERO

The Troc’ as it was known at 515 George St attracted 5000 couples a week to its public dances and banquets.

The epitome of Hollywood glamour, the Trocadero opened in 1936 and more than one million pairs of feet would pass through the beautiful Art Deco “palais de dance” including royals, governors, presidents and celebrities.

It was a class act with its marble foyer, scarlet carpets, shell stage and Art Deco auditorium, and throughout the ‘30s and ‘40s attracted the best big bands, dancers and musicians.

The Troc thrived through all the fads from jazz to crooners but the rot set in with the arrival of rock’n’roll.

By the late 1960s, big bands and swing were over, new clubs had arrived and the Troc closed its on 5 February 1971. It was demolished to make way for the Hoyts Theatre complex.

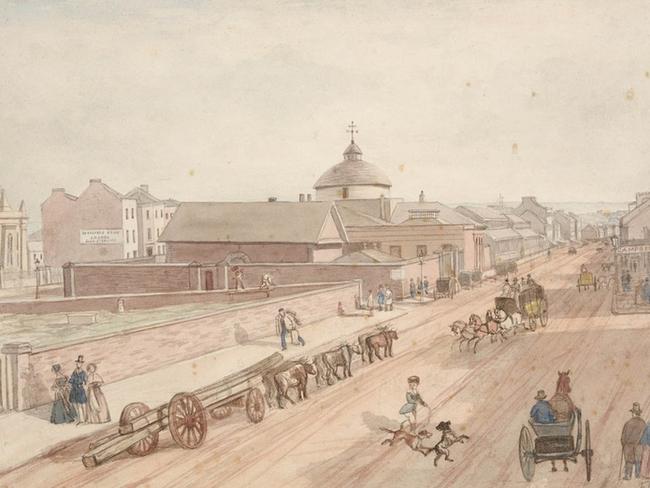

SYDNEY’S OLD BURIAL GROUNDS

The first resting place for the city’s dead, the Old Sydney Burial Ground, was on the corner of George and Druitt streets where the Town Hall and parts of Town Hall station are today.

Dating back to the 1790s, the burial ground operated for 27 years under terrible management; it wasn’t consecrated, religions were interred indiscriminately and no records were kept. Overflowing by 1820, it was shut down and the dead were moved on to the new Devonshire St cemetery, bounded by Eddy Ave, Elizabeth and Chalmers Streets.

The Devonshire cemetery filled up rapidly forcing its closure in 1868. By that time, the Old Burial Ground had become a rancid mess where feral animals wandered among the open graves and bodies were dumped illegally.

The land was transferred to the City in 1869 for the construction of the Sydney Town Hall, and what remains could be retrieved were reburied at Rookwood.

But it was rudimentary and bodies and coffins have randomly popped up over the course of the last century as building projects disturbed the dead.

In 1901, the Devonshire St cemetery was resumed to build Central Station.

REGENT THEATRE

Built in 1928, this wonderful building with its beautiful interior at 487-50 George St (next to the Trocadero) was a famed picture palace and popular venue for concerts, stage shows, and big musicals before it was knocked down.

Opening with Greta Garbo film Flesh and the Devil, it closed with a screening of the documentary Ski Time on 26 May 1984.

The heritage-listed cinema was demolished amid public protests in 1988 and the lot sat empty for 20 years before it was turned into a high-rise building complex.

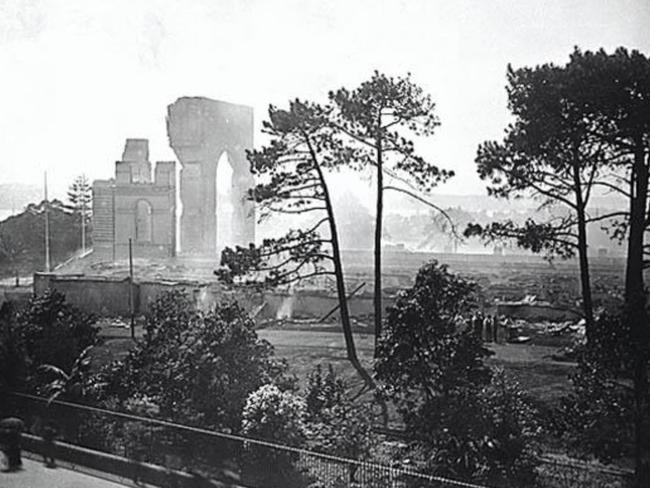

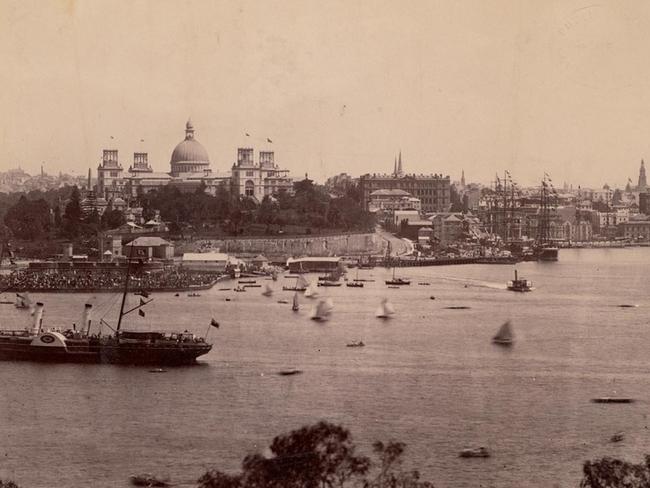

SYDNEY’S GARDEN PALACE

Bigger then the QVB and stretching from the State Library to the Conservatorium of Music in the Botanic Gardens, the palace’s towers and 65m-high dome would have been the first seen by visitors arriving in the harbour through Sydney Heads.

Modelled on London’s Crystal Palace, it was purpose-built for the 1879 Sydney International Exhibition and was designed by Colonial Architect James Barnet.

But a mysterious fire on September 22, 1882, turn it to cinders and little more than the sandstone gates and a few statues remain.

Despite being one of the most captivating buildings Sydney has ever seen, the Garden Palace is largely absent from popular history and most Sydneysiders have never heard of it.