Lindt cafe siege inquest: How police appeared to have no plan

LINDT Cafe siege police appeared to have had no plan except to wait until their hand was forced by hostage-taker Man Monis.

NSW

Don't miss out on the headlines from NSW. Followed categories will be added to My News.

AS THE hours dragged on during the Lindt Cafe siege, the two most senior police officers in charge of tactics knew they needed more than hope if the hostages were to be freed unharmed.

Hope is not a plan. That was the mantra drummed into the state’s frontline counter-terrorism officers.

At the inquest into the siege this week, a team of UK counter-terrorism experts said: “In IS-inspired sieges, the maximum chance of survival of the hostages is achieved through early intervention by police as opposed to the hope that, given time, the hostages will be released or escape.”

The 13 terrified hostages still held captive inside the Lindt Cafe when the police night shift took over at 10pm on December 15, 2014, were hoping they would be rescued.

Gathered nearby, their distraught families were hoping the worst would not happen, hoping they would all get out alive and unharmed. But to senior police that night, hope was not a plan.

“Yes your honour, I do accept that. The buck stops with me” — police forward commander

In the Police Operations Centre (POC) was the head of the crack Tactical Operations Unit (TOU), a superintendent whose role that night was “tactical adviser”. The POC was headed after 10pm on December 15 by Assistant Commissioner Mark Jenkins.

In the Forward Operations Centre centre there was a chief inspector, know as “tactical commander”, that night. The forward commander who was on at the same time as Jenkins was a detective chief superintendent who cannot be named.

Both the tactical adviser and the tactical commander have used the motto “hope is not a plan” in their evidence to the inquest — a flashback to their training under the retiring Arabic-speaking Deputy Commissioner Nick Kaldas who took over the counter-terrorism command in 2006.

It was a phrase he used often. But the inquest into the deadly siege has heard that, despite hope not being a plan, police had backed themselves into a corner.

They had given themselves just two options. One was to hope that they could persuade Monis, even though he had refused to talk to negotiators since declaring the siege on behalf of IS at about 9.40 that morning, to surrender, take off the backpack in which he claimed to have a bomb, and walk out into Martin Place with his hands up. The other, as confirmed this week by the forward commander, was almost unbelievable. It was the death of a hostage.

Because of the threat of a bomb, it was only if a hostage died that he would order TOU officers to commit their only other option, their emergency action plan, to storm the cafe, he said. This is exactly what happened at 2.13am on December 16 after Monis shot dead the quietly heroic cafe manager Tori Johnson.

Barrister Katrina Dawson, a mother of three who had arrived at the cafe the day before at 9.15am for coffee with two friends, died after being hit by seven fragments of police bullets as she hid under a chair.

That harsh choice the police had somehow left themselves by 2.13am was bluntly spelt out by NSW State Coroner Michael Barnes as he quizzed the forward commander this week.

Police had found no evidence of bomb-making equipment in Monis’ home but they still believed he had an IED (improvised explosive device) and would detonate it, killing both hostages and police.

“On that basis you accept on the night that you could not order (the TOU to go in) unless someone was killed,” Barnes asked.

“I accept that your honour,” were the commander’s damning words. He denied a suggestion by counsel assisting the inquest, Jeremy Gormly SC, that the whole siege was managed by police on the basis they would not storm the cafe unless someone was killed or seriously injured.

It’s not that there were no other options, just that they were not pursued, according to the evidence given.

There was a direct action plan drawn up, backed and preferred by the tactical commander and the tactical adviser. It was supported by military advisers with the Australian Defence Force who were in the POC.

The TOU officers who had been standing outside the cafe in their 25kg of uniform since first thing that morning were itching to use it. It enabled them to storm the cafe at a time of their choosing, a tactic they believed much safer than the alternative.

But it was never approved by successive commanders at the POC. The option to use it was never on the table.

Another option that has emerged was for negotiators to have used a third party to try to get Monis to speak to them. UK negotiation experts gave evidence by video-link this week that those third parties could have included one of Monis’ barristers, Michael Klooster. Klooster had acted for him in a Family Court matter and had spoken to Monis in the Lindt Cafe that morning, December 15.

Another possibility was one of his solicitors, Manny Conditsis. Both lawyers had offered to liaise with Monis because they believed he trusted them. Another was the Grand Mufti of Australia.

The inquest has heard police negotiators were reluctant to use third parties for various reasons, including they were not trained and could make things worse. But it was something they would have considered if the siege continued.

One of the experts, Chief Superintendent Kerrin Smith from Durham in the north of England, acknowledged UK police had changed what had been a similar policy after criticism that not using third parties had resulted in deaths.

But the Lindt negotiators had made no “substantive progress” in 17 hours, she said.

Questioned by Mr Gormly, the forward commander agreed the “only tool in his tool bag” was to continue with the tactic of contain and negotiate, with the emergency plan if “things went wrong”.

“Time is my friend,” he said often in his evidence. A belief, it was pointed out, that was at odds with what the UK counter-terrorism report said about “in IS-inspired sieges the maximum chance of survival of the hostages is achieved through early intervention”.

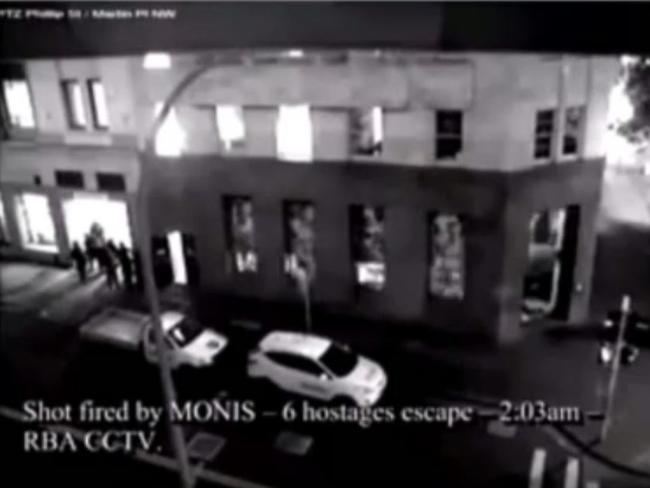

Time was definitely not on his side in those final 10 minutes of the siege — the crucial time after Monis fired his first shot at six escaping hostages at 2.03am.

“We’re not at an EA. It’s not emergency action. No EA. It’s not the EA,” the commander picked up the phone and said to Jenkins.

In even more examples of how poor communications that night let down the police, and the hostages, no one told the forward commander the escaping hostages believed Monis had been shooting at them. Nor was he told when Monis forced Johnson to his knees. Nor when Monis was heard firing a second shot that went into the ceiling.

He said he did not want to make a “kneejerk” reaction and had things to work through like allowing his team time to gather evidence among the “confusion” and they were “flying blind”.

Coroner Mr Barnes: “Do you accept that the 10 minutes before something else forced your hand was too long.”

Forward commander: “Yes your honour, I do accept that. The buck stops with me.”