Junior doctors being driven to suicide by a grinding workload

THE shock of a spate of talented, highly intelligent, resilient junior doctors in NSW taking their own lives has rocked all levels of the Australian medical community.

NSW

Don't miss out on the headlines from NSW. Followed categories will be added to My News.

THE shock of a spate of talented, highly intelligent, resilient junior doctors in NSW taking their own lives has rocked all levels of the Australian medical community.

With the spotlight now fixed on medicine’s ugly underside, authorities once again are questioning how to fix the industry’s culture and protect the 3300 medical students who will transition into the workplace this year.

In the wake of the three deaths since September, the hospitals that employed those talented junior doctors have been swift to spell out the support networks they offer, from helplines to performance trainers and even yoga.

Yet those at the coalface of the problem don’t argue that the supports aren’t there — it’s that doctors in the grips of mental despair are too fearful to access them.

In NSW, doctors who confess mental health issues to another doctor must be reported to the Medical Council of NSW by the treating doctor.

The council will investigate the issue and, if they act against the doctor, such as putting restrictions on their practice, they inform the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (AHPRA).

AHPRA is a powerful body that controls a national medico register and updates the public list if a doctor has restrictions on their practice.

This transparency is to ensure patients can easily check if their doctor is registered and reputable but the Australian Medical Association (AMA) says it is detrimental to a doctor’s mental health.

A doctor’s all-consuming fear of being on the radar of any regulatory body stops them seeking help.

Perth-based obstetrician and gynaecologist Dr Michael Gannon, president of the AMA, says Western Australia opted out of mandatory reporting and other states must follow suit.

AMA NSW President Brad Frankum agrees.

“It is clear to me that provisions such as mandatory reporting are stopping doctors and students from accessing care, or are making them fearful of the consequences if they do require support,” Dr Frankum wrote in an open letter after the suicides.

“We have to change this because it is not making our doctors or our patients safer.”

He told The Saturday Telegraph: “There is a real problem with disclosure laws at the moment … it just drives people underground and leaves them not wanting to disclose.”

“We need to look at an exemption for a treating doctor to treat a patient confidentially and not report them unless they have a fear the person is going to harm somebody else and we need to reassure our junior colleagues that in fact they’re not going to be discriminated against if they have a mental illness.”

Changes to mandatory reporting are also on the radar of Health Minister Brad Hazzard. Following The Saturday Telegraph’s revelations about the spate of deaths, Mr Hazzard instructed his department to collect information from all hospitals on the number of suicides and the broader issues.

Mr Hazzard will be briefed within a month by the investigation and he has promised to implement any “evidence-based” changes.

Australian Medical Association Council of Doctors in Training chairman Dr John Zorbas knows the stresses of being a junior doctor personally as he studies towards expertise in intensive care medicine and emergency medicine.

He believes problems ramp up once medical students hit the workplace, especially in large hospitals. “Training doesn’t become the primary focus sometimes. It can be an afterthought and that’s where things can be dangerous with doctors working unsafe hours and junior doctors aren’t provided with backup or training,” he said.

After university study, aspiring doctors do a 12-month internship.

“The internship is quite a protected space, it’s well-regulated, you’re not worried … it’s what happens afterwards when things get complicated,” Dr Zorbas said.

After completing the internship, the young doctor will continue work in the hospital while competing for places at colleges, which then lead to specialties.

The entire process can take up to 15 years of non-stop fulltime work dealing with life and death for at least 50 hours a week with 10 to 30 hours of study on top of that — and it doesn’t come cheap.

“Some trainees will pay tens of thousands of dollars a year in further education,” Dr Zorbas said.

He agrees that fear stops doctors seeking help if they are struggling to cope.

For BeyondBlue board member Dr Mukesh Haikerwal the latest spate of young doctor deaths is “heartbreaking” and something he feared after a damming report in 2013 went largely ignored.

It found doctors had significantly higher rates of psychological distress and attempted suicide compared with the Australian population and other professionals.

Perhaps unsurprising for those in the industry, the levels of high psychological distress were most severe among doctors under 30.

They had rates of 5.9 per cent compared to 2.5 per cent for other young Australians.

A quarter of doctors reported having suicidal thoughts prior to the last 12 months and 10 per cent had them in the recent year — much higher than the general population.

There were also higher levels of “burnout”, which were higher among young doctors than medical students.

“This suggests that the transition from study to working may be a particularly difficult time for newly trained doctors and they may require additional support,” the report concluded.

Two years after that report, a spate of junior medicos in Melbourne took their lives.

“That report was published in 2013 and it breaks my heart that we still haven’t stemmed the flow of people doing this,” Dr Haikerwal said.

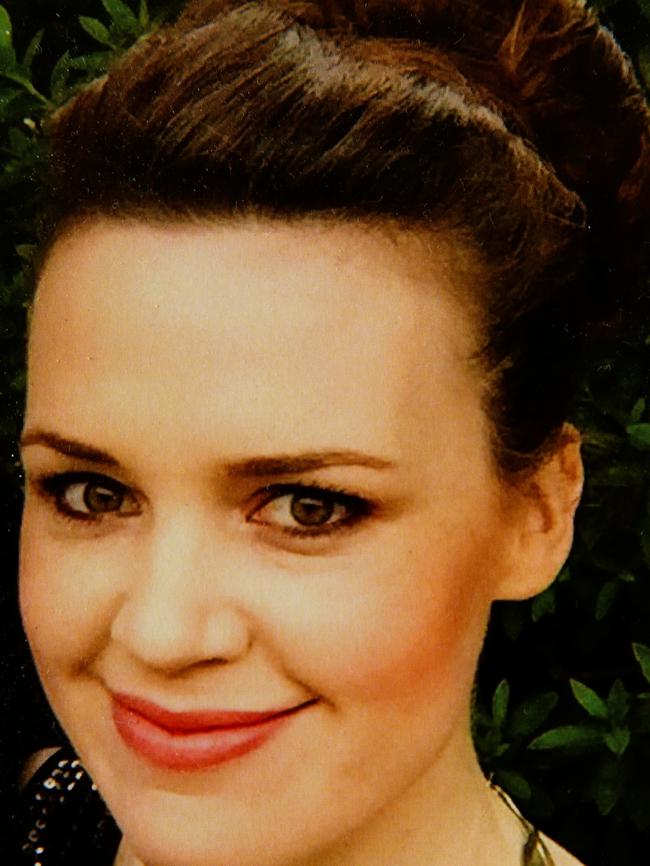

Dr Chloe Abbott died on January 9, 2017, three months before she was to sit an exam which, if she passed, would have led to specialist training to be an endocrinologist.

The qualified podiatrist had been studying for the exam for more than a year.

“The day before she passed away I begged her to leave medicine behind and go back to podiatry and go back and work in a profession that seems to have a better work-life balance and seems to have compassion, a human side,” her sister Micaela said.

Dr Abbott, a highly regarded junior doctor who met with politicians while she represented the AMA, even moved house so she was closer to a study group and St Vincent’s Hospital, where she worked.

Her mother Leonie Eagles said Chloe could go for weeks without speaking with her family.

Her silence wasn’t malicious; she was just so swamped with work and study.

“She would come home from work and do another six or eight hours of study, all the while being on call, than try to get off to sleep, than wake up again to go and function at a major teaching hospital,” Ms Eagles said.

“To think that she had such a brain, she could pull anything out of the vault but yet you still think you have to study for more than 12 months to pass these ridiculous exams and pay $5000 for the privilege.”

Micaela saw her sister crushed by the “completely unsustainable” rigour of the profession.

“You’ve got all these TV shows like Grey’s Anatomy and it sensationalises it and makes it look like a glamour career but it’s a unforgiving career, you have no work-life balance and it seems like anything they do is not good enough. There is always something else they can do to be better.”