Inside the electronic tracking scheme watching domestic violence monsters

As debate rages over whether electronic monitoring should be expanded to include bailed domestic violence offenders, The Saturday Telegraph looks at how those convicted are tracked.

NSW

Don't miss out on the headlines from NSW. Followed categories will be added to My News.

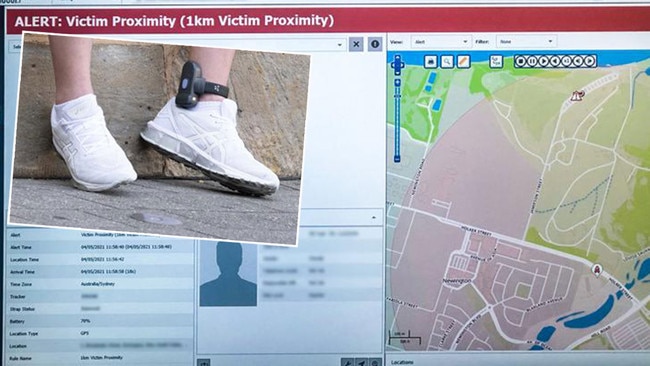

A convicted domestic violence offender approaches the home of his victim.

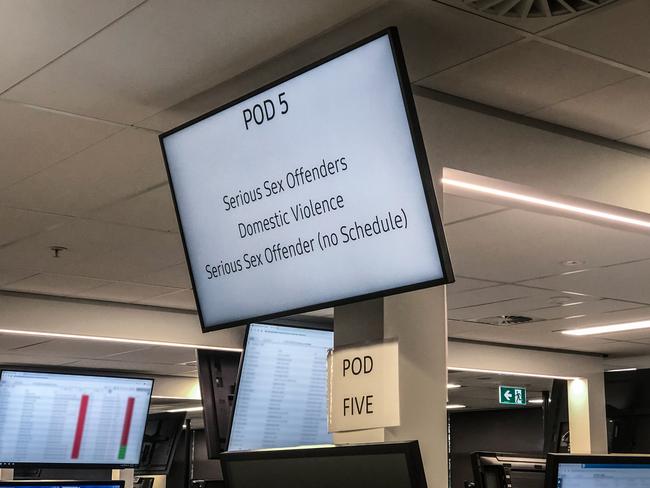

His movements can be seen on a map displayed on a monitor being watched by a specialist team of officers working in a NSW Corrective Services building located in an undisclosed area of Sydney.

The officers can see where he is going as he is wearing an electronic monitoring device as required by the court.

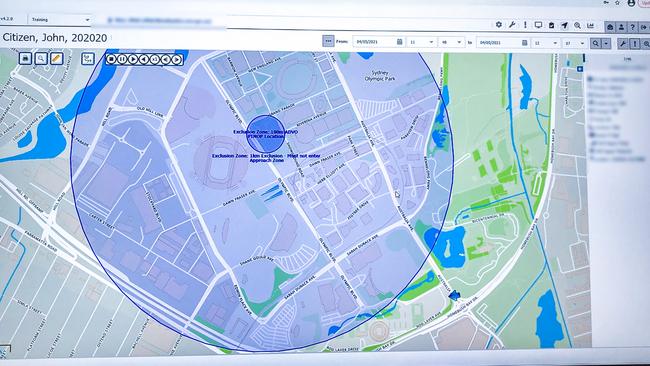

His victim is located in an exclusion zone, which is off-limits to the offender.

But on this occasions, he appears to be ignoring it.

The officer tracking the offender’s movements in real-time calls one of more than 1500 NSW Community Corrections officers located around the State.

The most frequent scenario results in the officer calling the offender to find out why he is where he is, what is going on in his mind and an assessment of his emotional state, explains NSW Corrections Acting Assistant Commissioner Ellen McCarroll.

Occasionally, there is an innocent reason for the offender travelling close to an exclusion zone.

At other times, the offender cannot be reached by phone, prompting a call to police.

On one of the those occasions, police responding to a call from the monitoring team found the offender with weapons – an incident that serves to remind those involved in the NSW government-run Domestic Violence Electronic Monitoring (DVEM) program the critical role they play in ensuring the safety of victims.

The work is also about identifying the behaviour that occur before an offender might think about offending – and being a circuit-breaker, McCarroll said.

“Does he pace around before he offends? Is isolation a risk factor? What does he do in the lead-up to offending,” she said.

“Our response is always very quick. Our staff will call and have a conversation. They will ask what is going through his mind, assess his mood.”

The screens are monitored around-the-clock – “and our phones are always on,” McCarroll said.

Established in 2017 as part of the then Coalition government’s Domestic and Family Violence Blueprint for Reform, the program applies to “high risk” offenders on parole, on an intensive corrections order, or convicted of domestic violence offences.

Following the death of mother and childcare worker Molly Ticehurst, questions are being asked whether the program should be expanded to offenders on bail.

The Coalition wants State-supervised electronic monitoring to apply where the prosecution opposes bail or seeks monitoring for accused persons before they can be granted bail in serious personal violence offences in a domestic relationship.

The Minns government — which will on Monday bring to Cabinet its highly-anticipated bail reforms — has not ruled out electronic monitoring entirely, although it is likely to be the subject of future discussions.

A government source said the concern was that those who are motivated to kill or seriously injure their intimate partner would not be deterred by an electronic monitor.

Since the program began, the movements of 673 domestic violence offenders have been tracked.

This week, 33 individuals were being monitored.

Officers monitoring the offenders watch to ensure they don’t go within a set exclusion zone – such as a specific suburb – listed on their Apprehended Domestic Violence Order (ADVO).

To track their movements, each offender is fitted with an electronic ankle bracelet which monitors their location at all times.

Offender movements are not only tracked to protect the victim, but to also ensure they are meeting parole conditions such as attending programs to address their behaviour.

While electronic monitoring had its place, it was part of a broader regime which also involved regular in-person supervision and check-ins by community corrections officers trained to spot psychological or behavioural changes, McCarroll said

“That is something technology cannot do – technology can track and trace but it cannot look into someone’s eyes, it can’t hear the words being used, or the way something is said. Our officers are trained to analyse all of these things and more,” she said.

“The in-person supervision of someone when they’re in the community, and having face-to-face contact with that offender, especially those convicted of domestic violence-related crimes, is an absolutely critical part of supporting victims, their safety and our communities.”

Corrections Minister Anoulack Chanthivong said women had a right to feel safe in their homes.

“Any act of domestic violence is abhorrent, and the recent incidents that have occurred are tragic – women have a right to feel safe in their homes, on their streets and in their communities,” he said.