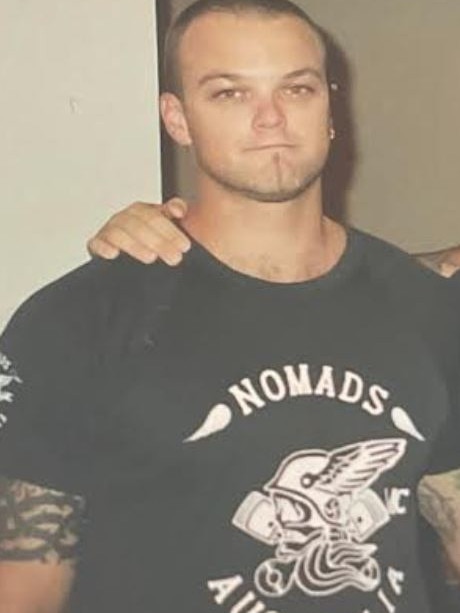

I Catch Killers podcast: Former Nomad bikie Duncan Burns reveals what bikie life is really like

As a member of the Nomads Duncan Burns thought that he was part of a brotherhood but once he got his patch he worked out it all wasn’t exactly as they preached.

NSW

Don't miss out on the headlines from NSW. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Duncan Burns has a warning for those caught in Sydney’s lethal gang war – don’t trust your “brothers” to stand by you when the bullets start to fly.

As a former Nomad who cheated death by millimetres after being shot by rival bikies, he speaks from experience.

“My so-called brothers didn’t give a shit about how things played out for me,” Burns told the I Catch Killers podcast to be released on Sunday.

“It was preached to me … this was a family.” But the flood of drug money into Australia has changed the bikie gangs, he said.

“Some of the older members became corrupted. Just more worried about dollar signs and making the money.

“It was only after I got my patch that I worked out it wasn’t exactly all that they preached.”

Burns spoke out in the wake of a bitter war between rival Sydney gangs that has claimed the lives of 16 people so far.

At 47, Burns has sympathy for those caught in the crossfire, just like he was a generation earlier.

“Wrong place at the wrong time,” he said. “In the middle of a gang war. It wasn’t by choice that I took that route.”

In 2005, Burns’ western Sydney chapter of the Nomads wanted to hold their annual memorial ride, to remember a past president.

At the time, they were at war with a rival bikie gang, who he asked not to name.

Riding in public meant danger, but the Nomad’s bosses “basically sat down and said ‘We’re not going to back down’.

“The word was put out – the memorial ride was going ahead regardless.”

That morning, Burns woke up “feeling sick in the guts and the little voice in my head was saying to me even then, ‘Don’t get on the bike’.

“But then my ego took over … ‘Just do what you got to do and get on’.”

His fellow Nomads agreed to meet up in remote locations then ride together so no one would be a lone target.

Burns was riding through Blacktown with his sergeant-at-arms and another life member, when they passed some parked cars.

“Something caught the corner of my eye. One of the guys was starting to lean out the window and next thing I hear the shot.”

The bullet went in through Burn’s back and out of his chest, missing his heart by millimetres.

“I blacked out due to my body going into shock,” he said, and came to still riding his bike on the wrong side of the road, heading into a roundabout.

Luckily, there wasn’t much traffic. Burns clamped one hand over his chest to reduce the bleeding and kept riding.

“I had to get to my vice-president’s place, which was around about a half-kilometre up the road.

“As I went through the roundabout … I looked in my side-view mirror and saw the car do a u-turn.”

He knew they were coming to kill him, so changed down a few gears and kicked the bike on.

Collapsing only when he got to safety, Burns came to a second time thinking of his four-month-old daughter.

Three days later, he walked out of hospital, tearing the IV tubes from his body and defying the nurses.

But back with the Nomads, when he needed support, Burns saw only division.

“If we weren’t at war with other gangs, we were at war internally.”

There were drug debts between members. If someone couldn’t pay, “he ended up being set up and bashed.

“Things would be videoed and shown to another member’s wife or used as blackmail.

“The longer I stayed around the realisation of how treacherous that life really is became more and more evident.”

Leaving wasn’t easy. Burns got into fights with other gang members, then he finally walked.

What followed was harder – he found work and lost it, got an addiction to drugs he’d first used with the bikies, and kicked it.

Today, Burns says he is happy. He now has a family, work that he loves and something to live for.