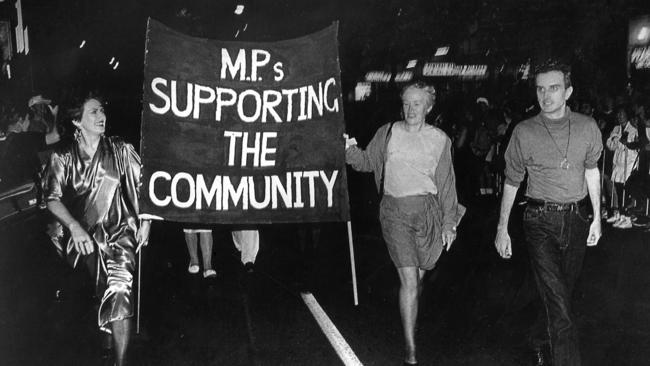

When Australia’s first Mardi Gras took place 40 years ago, what started as a peaceful march for gay rights and the decriminalisation of homosexuality descended into a violent protest, marred by police brutality.

It was June 24, 1978 and 53 men and women were arrested and some assaulted by officers as they were dragged away from the march and thrown into police vans.

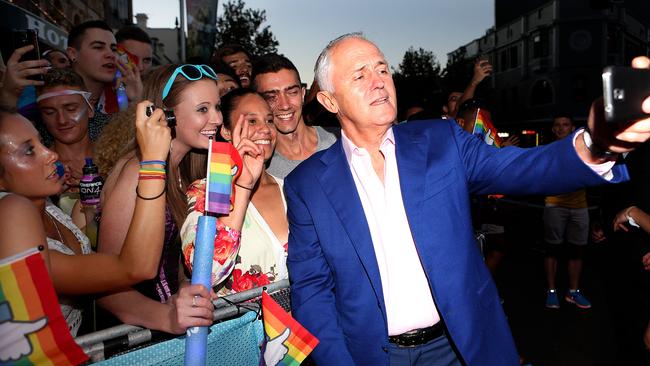

Today’s celebration could not be farther from the parade’s beginnings, following last year’s plebiscite and the legalisation of gay marriage in January.

This was when gay guys were regularly beat up and murdered ... it’s a really different climate now

The landmark, coinciding with the 40th anniversary, is another important milestone in the history of the parade.

More than 300,000 revellers are expected to join 12,200 marchers and 200 floats in tonight’s celebrations.

For “78er” Jim Carothers, it is a reality he never anticipated in his lifetime.

He was 24 when he participated in the first parade alongside his wife and their gay friends.

He was also one of the 53 arrested and beaten that night.

Talking to Saturday Extra, this is the first time Mr Carothers has publicly discussed the events that unfolded that night.

“There was a feeling of great solidarity that night,” he says. “We were marching as a unified group regardless of background.”

Marchers were celebrating International Gay Solidarity Day, commemorating the 1969 Stonewall Riots in New York.

“But it was not all just gay people marching, there were plenty of people like myself there to support human rights.

“I was marching mostly with a group of feminists chanting ‘not the church, not the state, women will control our fate.’ ”

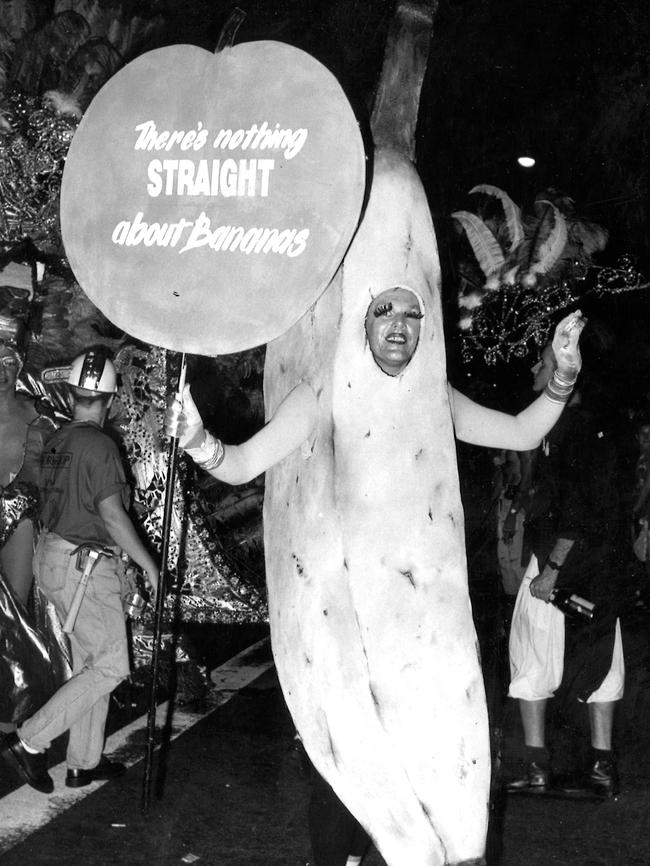

Unlike today, he said only a handful of people were in costumes, despite publicity at the time urging people to attend in fancy dress to encourage gay people in hiding to “come out” without fear.

“There was someone wearing a lot of feathers. I remember picking up these coloured feathers along the route, but most of us were in street clothes.”

Newspapers at the time estimated up to 2000 people participated in the first Mardi Gras.

Starting at Taylor Square in Darlinghurst, the parade was led by a truck mounted with a sound system down Oxford Street to Hyde Park.

Hanging on the truck were signs reading: “Repeal all anti-homosexual laws and end police harassment of homosexuals”.

The Australian’s Amanda Wilson reported the mood of the parade shifted when police confiscated the truck.

“March organisers believe the confiscation of the truck caused the spontaneous crowd decision to demonstrate instead of dance,” she wrote.

Carothers says the violence “didn’t just happen at the snap of a finger” after the music was taken away.

“Police initially stopped us, broadcasting, ‘you can’t go on, everybody disperse.’ But there was such a great sense of momentum built up that people didn’t want to stop, so we decided to march to Kings Cross.

“We definitely had a receptive audience. There were plenty of people barracking on the footpath.”

The parade only had approval to march to Hyde Park, however dozens of police began to block the protesters by parking cars across Darlinghurst Rd and linking arms.

“It’s almost remarkable we got as far as the fountain (Kings Cross’s famous El Alamein fountain),” says Carothers. “The police started grabbing people and hauling them off to throw them into the paddy wagon.

“There was one person and the group were pulling them in one direction and the cops were pulling in another direction.

“In a moment of inspiration, I went around to this cop and got him in a bear hug while he was grabbing this kid and then another cop came and grabbed me from behind — the three of us tumbled on to the ground.

“It was the Neville Wran era, it was a police state, they were really violent. They made sure they knocked me a good one ... I’m sure I had a concussion ... then I was off to Darlinghurst police station along with six or seven other people in the wagon.”

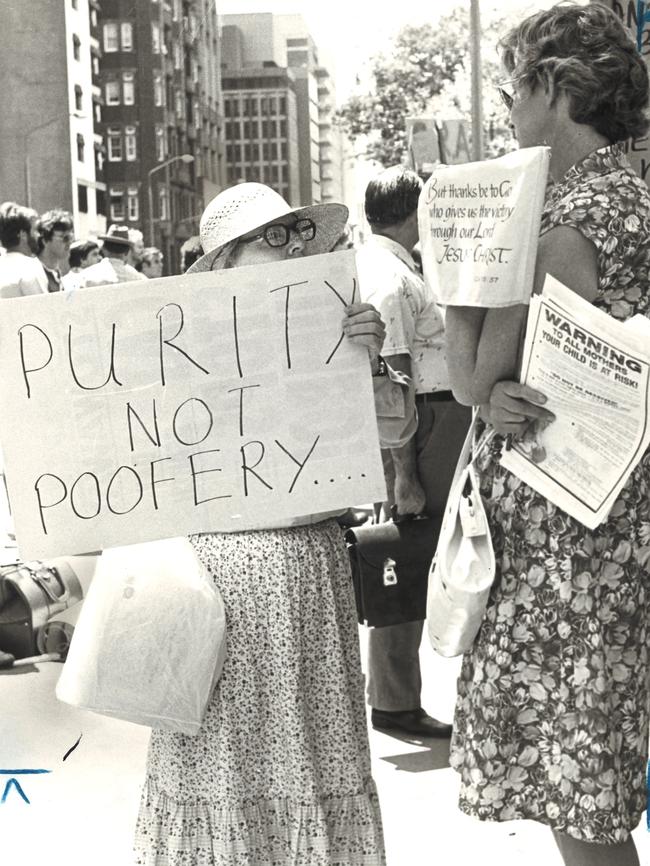

The police brutality flew in the face of comments made by Solidarity Day organiser Garry Bennet before the event — he believed they had the support of the police and would be protected.

“(We) are aware (violence) could happen, but we hope the fact that we have police approval will deter anyone who comes along to disrupt us,” Mr Bennet said before the event.

Reporter Wilson wrote that in one incident during the 1978 march, police took off their identification numbers and “waded into a crowd of homosexuals”.

Sydney Homosexual Organisation member Ian Smith said at the time what followed was a “good excuse to indulge in a bit of poofter bashing”.

“It is ironic that we were marching to commemorate the birth of gay liberation when riots and such attacks on homosexuals occurred.”

Carothers and the other 52 men and women charged that night were represented in a closed court the following day. Police prevented them all from entering and a large group of protesters joined them outside the court.

It too turned into a violent brawl between protesters and police.

“I remember somebody coming up to a cop and pinching his hat from his head and running into the crowd — somebody has a trophy to this day,” he says.

Carothers will be joining a record 250 other “78ers” today on a special float honouring the trailblazing activists.

“This is part of my history, this is part of my family’s history,” he says. “I’m acknowledging that I was there and lending my support. I have friends in my community who think it’s just a gay parade, but it’s a lot more than a gay parade.”

He says to witness the diametric shift in attitude towards the gay community in Australia over the past 40 years has been incredible.

“Deep down in my heart I hoped it would get to this point ... but I can tell you what the climate was like back then.

“This was when gay guys were regularly beat up and murdered ... it’s a really different climate now.”

Relations with police improved steadily after ’78 and two years ago NSW police officially apologised for the violence against protesters in the inaugural march. Assistant Commissioner Tony Crandell says 2018 will be one of the biggest parades in history.

“Police have been working with parade organisers and the LGBTIQ community to ensure a safe and fun night for all those taking part and supporting the event,” he says.

“I’m proud to say NSW Police will be taking part in the parade for the 22nd year.”

Gay activist Jane Marsden says Mr Carothers and the other 78ers have left an indelible legacy. “They are highly respected,” she says. “I think they never dreamt that Mardi Gras would be a worldwide phenomenon. I do think they have every right to be proud of what they started.”

Marsden is co-ordinating and managing a float titled Special Moments and Memories. The float celebrates the volunteers who have sustained the event.

“Over the years there have been tens if not hundreds of thousands of volunteers, activists, and staff who have built, nurtured and rescued Mardi Gras and those people should also be honoured,” she says.

Marsden started working on the parade 25 years ago, and a chance encounter in that first year motivated her to continue to support the Mardi Gras.

“I was standing in Taylor Square and saw a woman and a young man, about 15, at the barricades. I asked them, ‘what brings you here’ and the woman said, ‘this gives my son legitimacy and I want to thank you for that.”

“It did and it still does bring tears — I just think that’s what Mardi Gras is for. It gives us a chance to come together and celebrate in a joyful way the equality we demand. It’s still a protest but it’s a protest that is expressed in a unique way.”