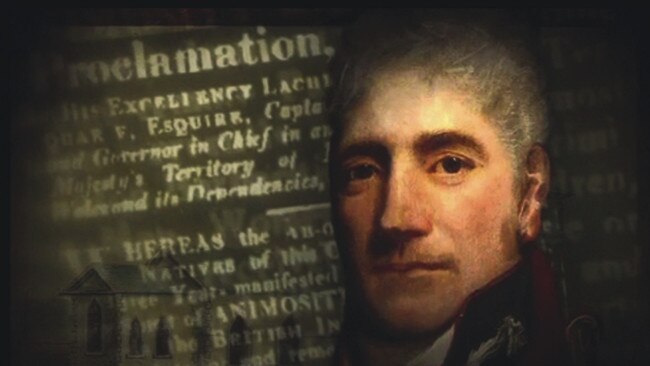

How Governor Lachlan Macquarie shaped NSW

The next time you jingle coins in your pocket, insist someone deserves a fair go, or talk about Australia’s skilled migration program, spare a thought for Lachlan Macquarie. These features of everyday life we take for granted were first imagined by NSW’s fifth governor.

The next time you jingle some coins in your pocket, insist that someone deserves a fair go, or even talk about Australia’s skilled migration program, spare a thought for Lachlan Macquarie.

Because one way or another, these features of everyday life we take for granted were first imagined by NSW’s fifth governor, a man who ruled from 1810 to 1821, and in ways great and small set us on a course to become a modern nation.

Born into a family with a respected clan name but not much else in Scotland in 1762, Macquarie left home at age 14 to join the army, his father having died a year earlier.

Fighting for the king, young Lachlan was sent first to the Americas, where he would serve in the battle against rebelling American colonists. He would also serve in the Caribbean.

Later he would discover a knack for diplomacy and administration during and after the fall of what was then Dutch Ceylon, or Sri Lanka.

MORE NEWS:

Australia Day 2019: Greens push to move date

Opinion: Warren Mundine on changing Australia Day

While the Napoleonic Wars raged in Europe, it fell to Macquarie to negotiate the holdings of the then-vast Dutch East India Company’s transfer to British hands and keep key ports out of France’s hands.

But it was when he officially landed in Sydney Cove on December 31, 1809, to take up his appointment as Governor of NSW that his — and Australia’s — future really took off.

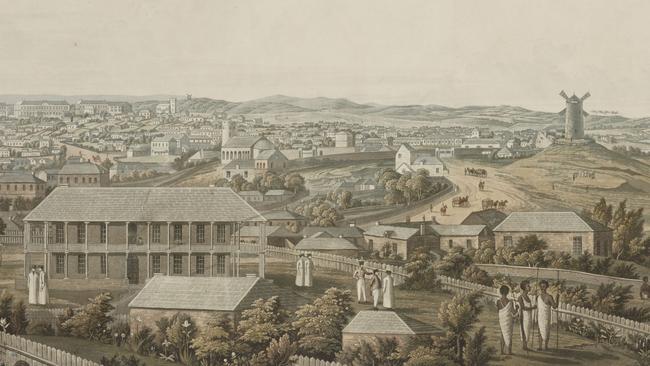

The Sydney that Macquarie landed in was a rough and chaotic place. The Rum Rebellion had only just ended on his arrival, the military stood over the justice system, and severe droughts in 1812 and 1813 tested the mettle of the young colony.

Among Macquarie’s first tasks was to break the hold of the army over the courts — something that would earn him lifelong enemies.

And, in perhaps the first example of the Australian “fair go”, he insisted that emancipated convicts be treated as the equals of those who had always been free.

“There are but two classes of individuals in the country,” Macquarie said.

“Those who have been transported. And those who ought to have been.”

Macquarie also wanted to see the new colony — and its new inhabitants — thrive. He wanted to see “the little man” as he called them do well, and on giving one man a grant of land at Mosman shouted, “Here is your (grant), now let me see you get rich!”

But none of this could happen without a local currency, so Macquarie bought 40,000 Spanish dollar coins and had a convicted forger cut out their centres and give them a new stamp so that they couldn’t be used elsewhere.

The new coins, known as “holey dollars”, were valued at five shillings, with the smaller pieces cut from the centre worth five pence. It’s no coincidence that Australia’s largest investment bank bears Macquarie’s name.

It was that desire to see new Australians make it, regardless of whether they had wound up in NSW because of some misdeed in the old country, that led him to offer grants of land to those convicts who wished to stay rather than return to England when their sentence was up.

Many got rich and it was those convicts who brought a useful skill to Australia who were most able to succeed, leaving their past mistakes behind to reinvent themselves in the new colony. The handiwork of Francis Greenway, a convicted forger who won his freedom, can still be seen across Sydney today. Acting as Macquarie’s chief architect, he drew up the plans for more than 200 buildings and public works, many of which can still be seen today, including Hyde Park Barracks, and the lighthouse at South Head.

Of course, Macquarie was as controversial then as he is today. In the 19th century his enemies attacked him for being too liberal with convicts. Back in London, a Tory government was appalled by Macquarie’s elevation of freed convicts and set up an inquiry that would haunt him for the rest of his life.

Today, activists denounce him for his rough treatment of Aboriginals, including claims that he ordered the mass murder of Aborigines at Appin — though Macquarie is also credited with establishing schools for Aboriginal children as well.

Whatever their verdict of his critics past or present, though, there is no escaping that much of our modern nation was born through the will of Macquarie.

Tributes to our greatest Aussies

There has been no shortage of attempts this year to diminish Australia Day — and with it, the unique success story of our nation that has made us the envy of the world.

But we know that what unites us is far stronger than that which pits us against one another.

That’s why, as Australia Day approaches, The Daily Telegraph is celebrating the Makers of Australia.

The men and women, past and present, who have through their talent, vision, and determination, contributed to make us who we are today.

We know that our history is not without conflict or pain. No nation can claim otherwise.

However, that’s no reason not to acknowledge our high points, either.

We celebrate the achievements of indigenous Australians, those who were among the first European settlers and also our recent migrants.

Politicians, generals, actors, writers, sports stars, doctors and inventors.

For a nation with a small population, we have huge talents — and we want to share them with the world.

And we think it only right that as Australia Day approaches we take the time to reflect and learn about the lives of those Australians who are responsible for forging our modern land.