‘Horrifying’ death toll of NSW children known to state government revealed

Almost a quarter of all kids who died in NSW last year were known to child protection authorities, which suspected them of being at risk of harm a new report reveals. It’s led to Opposition to suggest the government “hang its head in shame”

NSW

Don't miss out on the headlines from NSW. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Almost a quarter of all kids who died in NSW last year were known to child protection authorities, which suspected them of being at risk of harm in the three years before their deaths.

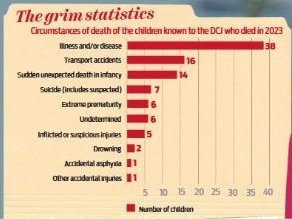

A new report tabled to parliament paints a devastating picture of at-risk children in NSW, revealing 96 children who died were known to the state government’s Department of Communities and Justice (DCJ), with seven of them dying by suicide, five from inflicted or suspicious injuries, and four dying in accidental circumstances.

The vast majority – 38 – died from illness and eight who died were living in out-of-home care at the time of their death.

Minister for Families and Communities Kate Washington told The Daily Telegraph the death of any child under any circumstances is “heartbreaking”, while child protection advocates called the situation “horrifying”.

“I extend my deepest sympathies to the families and communities who knew and loved these children,” Ms Washington said.

Opposition families and communities spokeswoman Natasha Maclaren-Jones said the Minns government should “hang its head in shame” over the figures.

“Almost a quarter of the children who died in NSW last year were already known to child protection authorities – children flagged as being at risk of harm, ignored until it was too late. This is not a tragic accident, it’s a systemic failure under their watch,” she said.

“Seven suicides, five suspicious deaths, and eight children dying while supposedly in out-of-home care – this isn’t a child protection system, it’s a conveyor belt of excuses.

“Under Labor, we have seen over 1000 foster carers leave in the past 12 months.”

According to the Child Deaths 2023 Annual Report, 96 children were “known to DCJ”, which means they – or their siblings – were reported to the department for being at risk of significant harm within three years of their deaths.

Fifty-six of the children who died had been reported to DCJ as experiencing physical harm, or being at risk of it, according to the report. Almost 40 of the children were also reported to be victims of, or at risk of, emotional abuse or neglect.

Most of the children died due to natural causes.

While the number of children who died while known to the system decreased from the 111 recorded in 2022, it has jumped since 2014, when 79 children known to DCJ died.

One casworker, who spoke to the Telegraph on the condition of anonymity, said they and their colleagues were overloaded with cases.

“One of the biggest issues we are facing at the moment is that there are systemic problems that we have within the department,” they said.

“We have high burnout because we are overloaded with cases.

“There is just so much work, we just don’t have enough time in the day to deal with it. We have high burnout because we are overloaded with cases.”

According to the report, in one case a 16-year-old boy known for “risk-taking behaviour” died in a road crash after DCJ had closed his case.

The boy had been reported due to concerns about his poor school attendance and an incident in which he stole a car and assaulted another young person.

His mother told a DCJ case worker her son was being supported by a youth justice caseworker and the boy’s case was closed.

In the following months, DCJ received three further reports with the same worries about the boy’s risk-taking behaviour and poor school attendance. He was also charged with assault and selling drugs.

In February 2023, DCJ received a report that he had died in a car crash.

Child protection advocate and chief executive of My Forever Family, Renee Leigh Carter, said the situation was “horrifying”.

“It should be a call to us that something needs to change, and urgently. The whole reason of having ‘risk of significant harm’ reports in the first place is that it means there is a threshold that has been met – there should be alarm bells and interventions put in place,” Ms Carter said.

“The number of cases that people need to see through is just too high … We have seen a massive turnover in caseworker roles due to heavy administration burdens and not spending enough time with children and families.”

Ms Washington acknowledged there was “more work to do”, but said the Minns government had found safe homes for 849 children by hiring 200 emergency foster carers after the former government stopped recruiting.

“We’ve also signed a historic deal to increase caseworker pay to attract and retain caseworkers,” she said.

Lifeline 13 11 14