Homicide detectives go back in time to catch killers and solve the 700 unsolved cases since 1970

FOR the cold case homicide detectives who spend years and even decades working tirelesslyto solve the state’s most baffling murders, clues can come from anywhere and they will stop at nothing to solve a crime.

NSW

Don't miss out on the headlines from NSW. Followed categories will be added to My News.

FOR the cold case homicide detectives who spend years and even decades working tirelessly

to solve the state’s most baffling murders, clues can come from anywhere.

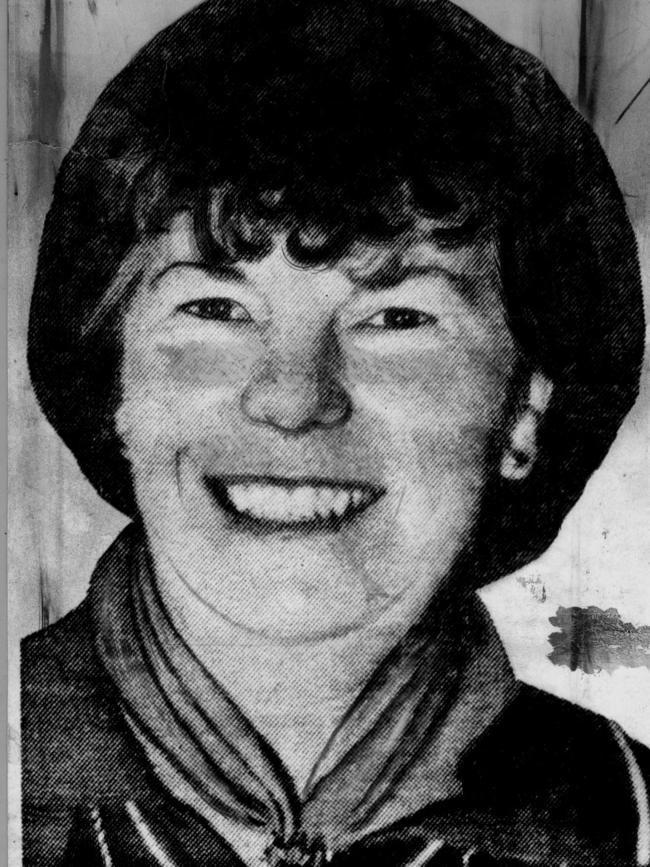

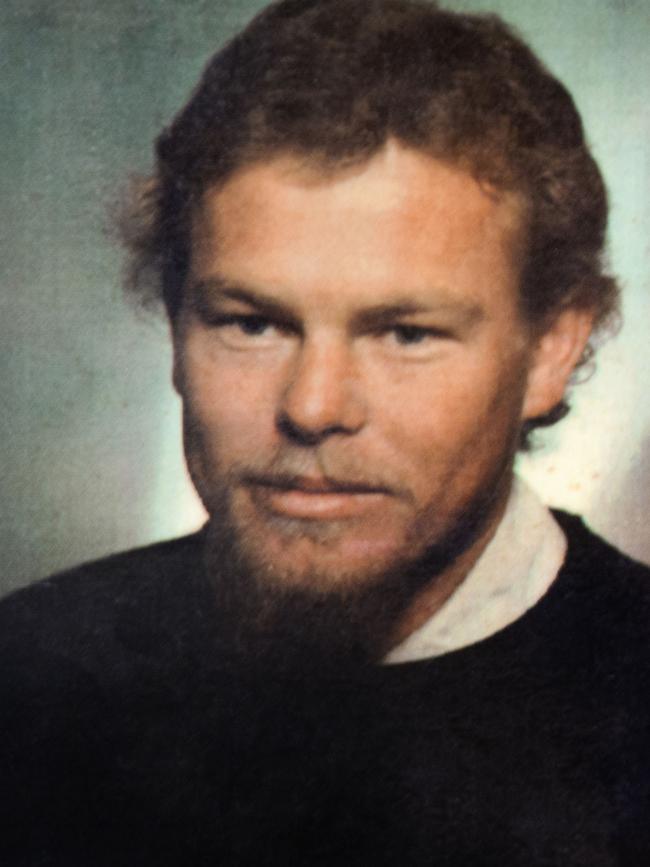

There was exhibit C-783410, which included human hairs vacuumed by police in 1983 from the boot of a car owned by Robert Adams, for 33 years the main suspect in the murder of nurse Mary Wallace.

The hairs were submitted for mitochondrial DNA analysis, which had not been invented decades ago, and matched those kept from Ms Wallace’s hairbrush.

Last month, Adams was convicted of her murder.

Then, last week, police asked Downing Centre Local Court to order a suspect in the stabbing murder of Double Bay restaurateur Rita Caleo 26 years ago to have forensic tests on his left hand.

It has been alleged in court documents that Alani Afu walked out of Ms Caleo’s home in 1990 carrying a large, blood-soaked knife and had suffered a diagonal cut to the palm of his left hand.

Afu, 49, who was extradited from Tonga, is refusing to have his hand looked at, and the case has been adjourned.

The state Homicide Squad’s Cold Case Unit has now achieved the conviction of more than 14 killers who thought they had got away with it, and the historic murders of another seven people are before the courts.

In an exclusive insight into the work of the “time travel” detectives, Homicide Squad boss Mick Willing told The Saturday Telegraph how they have a new system to target cases where they believe they have a better chance of charging a suspect.

But with around 700 unsolved murders and missing people since 1970 on their books, Detective Superintendent Willing said the “million dollar question” was choosing which to investigate.

“There’s a real mystique around homicide investigations and there’s an ever great mystique around unsolved homicides,” Supt Willing said.

“It’s very difficult to pick one homicide over another homicide and that’s why we try as far as possible to stick to a process.”

The squad hits the cases as teams, reviewing them to see if exhibits can be subjected to new forensic tests like DNA — which has helped solve more than 70 per cent of cases. Then they look at whether witnesses are still around and increasingly use behavioural science, getting inside the heads of their suspects.

“I”m keen to explore how we can use criminal psychology,” Supt Willing said. “What are the dynamics around the suspect. Have there been domestic breakups we can take advantage of and buttons we can push?”

Despite numbers in the unit being ramped up from 23 to 35 last year, major investigations like the one that led to last year’s arrest of the man accused of the Family Court bombings and four murders tied up about half of the squad.

“It's a very difficult decision to pick one homicide over another homicide and that is why we have to as far as possible stick to that strict process,” Supt Willing said.

The reality is that some cases are unlikely to be solved, such as the murders of best friends and neighbours Marianne Schmidt and Christine Sharrock whose mutilated bodies were found at Wanda Beach in 1965.

While tips still come in naming various “killers” which are followed up, Supt Willing said there were more than 10,000 statements and documents on the case, a massive task to get on top of.

The squad was set up in the wake of the backpacker murders to stop the disappearance of missing people like Ivan Milat’s seven victims longer falling through the cracks.

Supt Willing describes the unit as time travelling detectives: “They have to pick up an old brief of evidence and think like the original detectives. We are reviewing the work of some of the best detectives who have ever thrown on a suit.

“A big part of unsolved homicide is not necessarily about finding the murderer. It’s about providing answers to families who have been waiting a long time.”

RELATED NEWS: MOVE TO BAN ATKINS FROM GAY NIGHTCLUBS

Last year he sat down with Mark and Faye Leveson, who wanted to find the body of their son Matt who disappeared in 2007 after leaving a Sydney nightclub with his older lover Michael Atkins.

After being acquitted of his murder and given immunity from a fresh potential perjury prosecution, Atkins three weeks ago led police to what he said was Matt’s gravesite but no body was found.

No homicide detective can let an unsolved case go. Detective Sergeant Luke Scott worked on the disappearance of 12-year-old Quanne Diec in 1998.

Working with detectives at Rosehill, four years ago he was involved in setting up Strike Force Lyndey to investigate her abduction.

When Vincent Tarantino was charged with her murder two weeks ago, he became the squad’s 22nd arrest.