History of Australia Day: Significance of January 26 date explained

Nothing divides the nation like January 26 but beyond the social media and talkback radio diatribes lie serious issues about what our national day means. We unpack the Australia Day debate.

NSW

Don't miss out on the headlines from NSW. Followed categories will be added to My News.

From the moment it became a national idea, Australia Day on January 26 has been contested.

But debate and division over the date has grown deeper and louder in recent years, as public attitudes shift over what the day does — and should — mean.

Invasion Day rallies across the country now rival the regattas and council celebrations, with a recent Essential Media poll finding 53 per cent of people supported a separate day to celebrate in response to First Nations sentiments.

Over half of Aussies saw January 26 as “just another public holiday’, the highest since 2015, and this year just 29 per cent were set to celebrate it.

Those in favour of Australia Day as it stands say it can be a day of unity telling all our stories, both the good and the bad. Others say it’s impossible to celebrate on a date of profound grief and mourning for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders.

How did we get here? We break down the issues.

A note to readers: This article may contain images of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander people who are deceased.

FIRST FLEET ARRIVAL

While most countries celebrate a national day marking their independence from colonisers, Australia’s national date marks the date a penal colony began in NSW.

January 26 1788 is when First Fleet commander Captain Arthur Phillip raised the Union Jack in Sydney Cove and proclaimed British sovereignty over part of the continent.

The 11 First Fleet ships under Phillip’s command had arrived a week earlier in Botany Bay with more than 1000 convicts on board.

Not impressed with Botany Bay as an anchorage, Phillip sailed north in gale force winds, found Port Jackson and began establishing a settlement at Sydney Cove.

When the move was complete on January 26, the British flag was unfurled, toasts were drunk, and muskets fired.

The formal proclamation of the NSW Colony was on February 7.

ABORIGINAL PERSPECTIVE

For many First Nations people, January 26 signifies the start of dispossession, epidemics, frontier violence, destruction of culture and families, exploitation and racist laws.

When the British arrived, the land of the Eora Nation was home to more than 250 individual, sovereign nations connected by trade, cultural values and spirituality.

According to The Australian Law Reform Commission, conflicts between settlers and Aborigines, and the devastation caused by introduced diseases and alcohol, reduced the Aboriginal population during the first hundred years of settlement from an estimated 300,000 to 60,000. Most who survived had their traditional ways of life destroyed or suppressed.

The concept of terra nullius, or land belonging to no-one, was the legal principle on which British colonisation rested.

That principle denied that Aboriginal peoples had been living in Australia for more than 60,000 years.

In 1992, when the High Court brought down its finding in the Mabo v Queensland (No. 2) case, it ruled the lands of the continent were not terra nullius at the time of settlement.

As such, many Indigenous and non-Indigenous people refer to January 26 as Invasion Day, Survival Day and Day of Mourning.

A NATIONAL DAY

January 26 has only consistently been a national public holiday since 1994. Before that, it was held roughly the Monday nearest to provide a long weekend.

Nor has January 26 always been our national day. States celebrated their patriotism on different days for more than century. In NSW, January 26 was initially “First Landing Day” or “Foundation Day”. Other states marked Regatta Day, Proclamation Day and Empire Day.

It wasn’t until 1930 that the Australian Natives’ Association (restricted to white men born in Australia) suggested an annual “Australia Day” celebration.

By 1935, all states had adopted the date January 26 as Australia Day.

The Federal Government didn’t take much interest until midway through the 20th century. The National Australia Day Committee became a federally funded council in 1984.

A DAY OF MOURNING

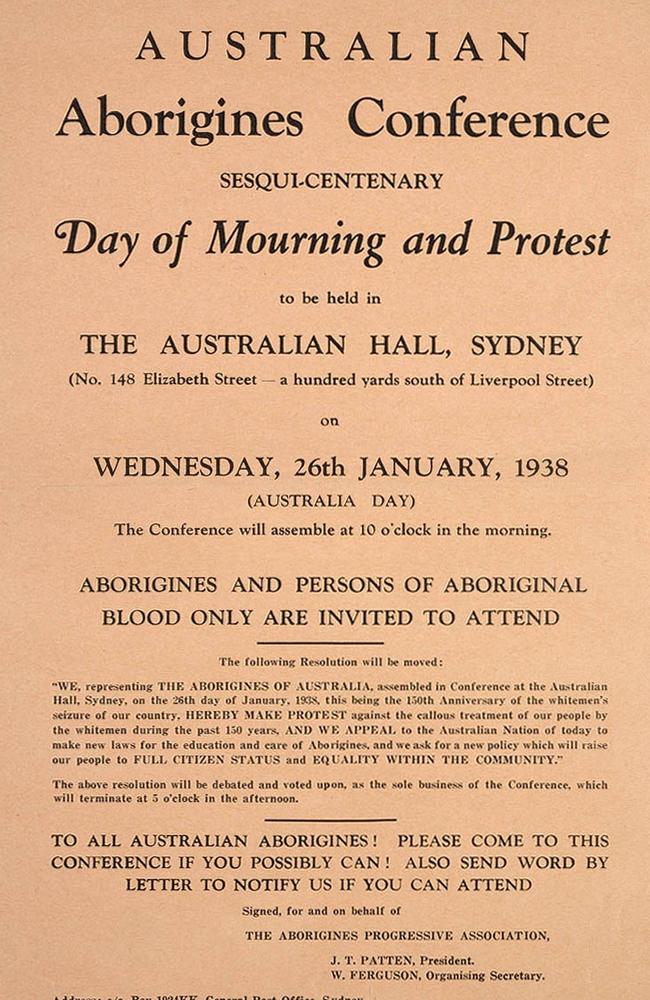

On 26 January 1938, Aboriginal people marked the first Day of Mourning and Protest in response to Australia Day celebrations.

The group of about 100 people marched in silent protest from Sydney’s Town Hall to the Australian Hall in Elizabeth St, having to enter via the back door.

The meeting — the result of years of work by the Australian Aborigines League and the Aborigines Progressive Association — passed the following resolution:

‘We, representing the Aborigines of Australia, assembled in conference at the Australian Hall, Sydney, on the 26th day of January, 1938, this being the 150th anniversary of The Whiteman’s seizure of our country, hereby make protest against the callous treatment of our people by the whitemen during the past 150 years, and we appeal to the Australian nation of today to make new laws for the education and care of Aborigines, we ask for a new policy which will raise our people to full citizen status and equality within the community.’

Organiser Jack Patten delivered a profound address, explaining: “Our purpose in meeting today is to bring home to the white people of Australia the frightful conditions in which the native Aborigines of this continent live.

“Aborigines through out Australia are literally being starved to death. We refuse to be pushed into the background. We have decided to make ourselves heard.

“White men pretend that the Australian Aboriginal is a low type, who cannot be bettered. Our reply to that is, “Give us the chance!”

“We do not wish to be left behind in Australia’s march to progress. We ask for full citizen rights, including old-age pensions, maternity bonus, relief work when unemployed, and the right to a full Australian education for our children.”

The 1938 Day of Mourning was the first time Aboriginal activist groups from different states had fully co-operated in a civil rights action.

Marking of the day has became an annual event for Indigenous people and their supporters.

CHANGING THE DATE

Calls to change the date from January 26 have continued to grow alongside awareness of Indigenous history so that Australia Day can be an inclusive celebration for all citizens.

Invasion and Survival Day rallies are now held across the country on January 26, and local governments, political groups and corporates have shifted on the day’s significance.

Cricket Australia was the latest to weigh in, removing the title ‘Australia Day’ from its January 26 matches in respect to those who view it as a day of mourning.

Local councils including Fremantle in WA, Yarra and Darebin in Victoria, and Byron Bay and Sydney’s Inner West in NSW have all cancelled traditional celebrations.

Such moves were criticised by the Federal Government, which stands firm on the date, saying it can and does represent all Australians.

However Reconciliation Australia, the National Congress of Australia’s First Peoples, the peak body representing Indigenous people in Australia, and the Healing Foundation, representing survivors of the stolen generations, all want a date change.

Chief executive of the NSW Aboriginal Land Council, Wiradjuri man James Christian, suggested more recently the fate of the date should be given to the people as some sort of plebiscite.

KEEP THE DATE?

Both non-Indigenous and Indigenous Australians also oppose changing the date.

Some see it as a day simply to celebrate Australia as a great country to live in.

Others as the day they became citizens, embracing the nation’s lifestyle, democracy, and freedoms.

Then there’s the argument that celebrations don’t have to be tied to historical events. Christmas, for example, is rooted in religion but many who celebrate give it no religious meaning.

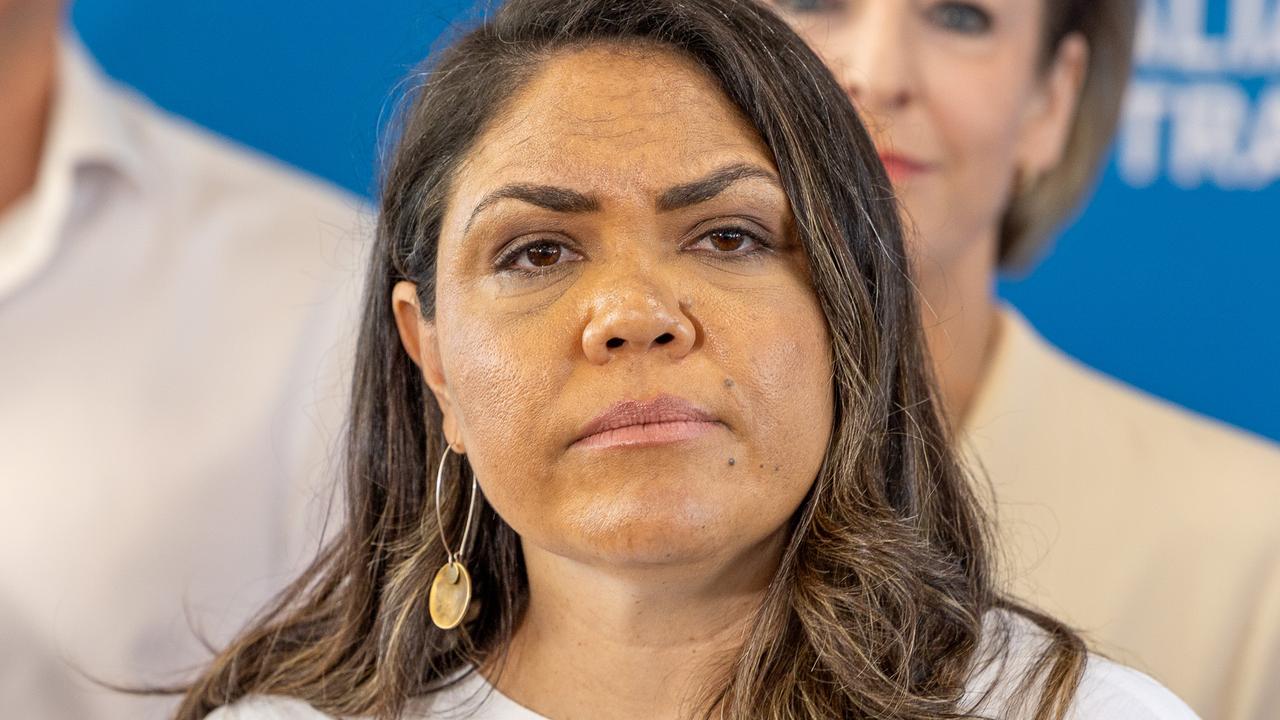

Others, such as Alice Springs Deputy Mayor and Warlpiri woman Jacinta Price, say protesting the date does nothing for the plight of marginalised Indigenous Australians.

In that view, a date change is an empty gesture and that more important changes, such as a treaty, constitutional recognition, self-determination and ‘closing the gap’ should be prioritised.

Finally, there are those who believe Australia Day can be both a day of reflection on injustices suffered and a celebration.

The National Australia Day Council takes such an approach, acknowledging the date has multiple meanings: it is Australia Day for some, and it is also, for some, Survival Day.

“Our national day provides an opportunity to acknowledge and learn about our nation’s past. It’s a time to reflect on and learn about our national journey including the ongoing history, traditions and cultures of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples.”

Minister for Indigenous Affairs Ken Wyatt agrees, saying Australia Day should remain on January 26 but both the good and bad of the nation’s history should be marked on that day.

“I want to see all Australians celebrate our Indigenous heritage, promote and support truth-telling to recognise and acknowledge our shared history, and work together to heal these past wounds so we can walk together towards a brighter, reconciled future,” he wrote for The Daily Telegraph. “Australia Day is not a day for hostility – or a day to discard the great achievements of all Australians who have built this great nation, and in recent months inspired us all.”

ABOLISH THE DATE

More recently, calls to abolish the date altogether have grown with advocates arguing a national day can never be one of unity until deeper structural reforms occur.

That means greater change including constitutional reform, truth-telling about the nation’s shared history, the negotiation of a treaty and addressing disproportionate rates of Aboriginal incarceration and other social issues including healthcare and education access.

Australia remains the only Commonwealth country to have never signed a treaty with its Indigenous people and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders are not mentioned in the nation’s constitution.

A PATH FORWARD

For many, only greater strides on the path of reconciliation will shift the impasse.

According to the 2021 State of Reconciliation report, The Uluru Statement from the Heart and a constitutionally enshrined Voice to parliament are the strongest way to achieve this.

The 2017 Uluru Statement from the Heart — directed to the citizens not the politicians of Australia — is a plea to the people of the nation to change the constitution to allow Indigenous Australians a voice in the laws and policies made about them.

Many Aboriginal leaders including Labor MP Linda Burney have said Uluru’s substantive constitutional and political proposal was vastly more important than changing the date.

You can read the Uluru statement here.

The Uluru statement proposes three key elements for reform: “Voice, Treaty, Truth”.

That means, a First Nations voice to parliament enshrined in the constitution to allow an advisory body of traditional owners to advise on policy affecting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. The Federal Government is funding a “co-design” process.

It also seeks a Makarrata Commission to supervise a process of agreement-making (or treaty) between governments and First Nations, and truth-telling to build a broader understanding of our shared history.

The report found strong evidence of progress in Australia’s journey towards reconciliation.

A 2019 Essential Poll found 70 per cent of respondents supported constitutional recognition.

And three years after the Uluru Statement, truthfully telling and accepting Australia’s history was overwhelmingly endorsed in the 2020 Australian Recognition Barometer by 93 per cent of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and 89 per cent of Australians in the general community.

While there has been significant progress in the government’s commitment to establish a body – a “Voice, there is still a way to go. You can read the interim report here.

Is it time for a new date or should it remain?

Share your thoughts on the issue below.