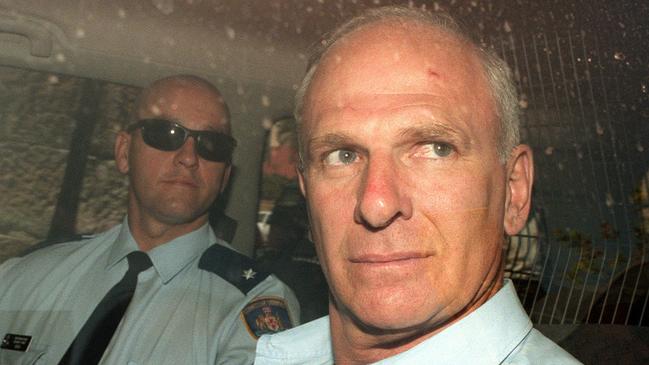

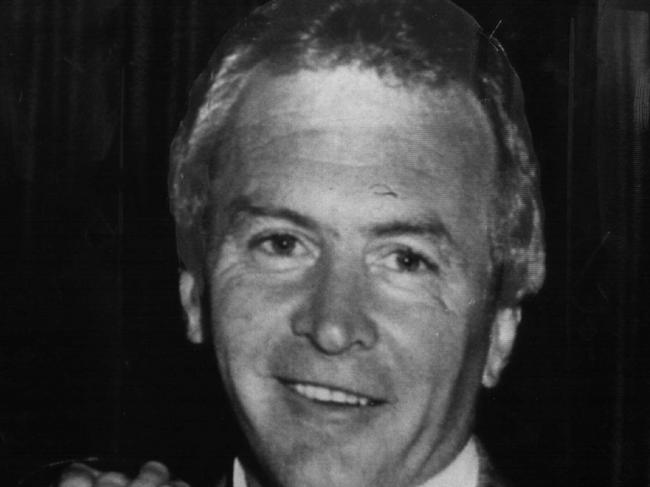

Graham Henry’s brutal life: From one of Sydney’s baddest men to a doting grandfather

In a shockingly candid and confronting interview, notorious old school Sydney gangster Graham Henry opens up about his life in the heart of the ‘Sin City’ underworld.

NSW

Don't miss out on the headlines from NSW. Followed categories will be added to My News.

It was inevitable that Graham Henry was always going to be a gangster.

It’s not an excuse for his behaviour and he is not looking for exoneration but Graham Henry’s violent upbringing is at least some kind of an explanation for the path that followed, that turned him into one of Sydney’s most notorious criminals for three decades from the 1970s onwards.

It was a time when he kept company with some of the most reprehensible individuals from Sydney’s underworld, brutal thugs who ruled the streets and operated with impunity having been given the “green light” from a corrupt police force.

In reality it’s astonishing that Henry, who was more commonly known by the offensive and inappropriate term “Abo”, is even alive or free to tell his story given what happened to his contemporaries. These included gangland boss Neddy Smith (dead), corrupt cop Roger Rogerson (jailed for murder) and hitman Christopher Flannery (dead).

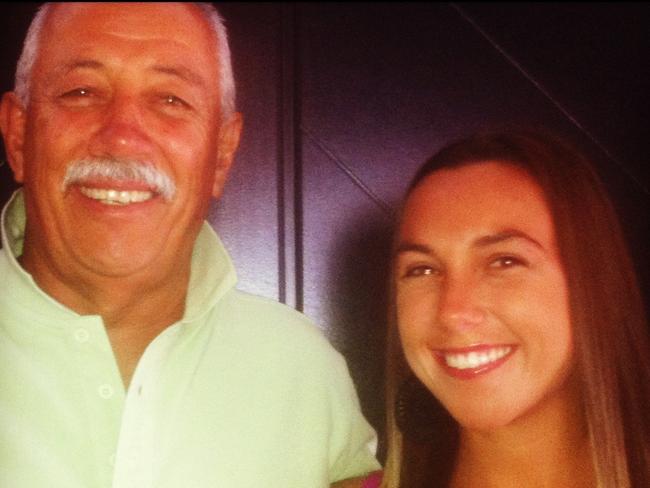

A father of three and a doting grandfather of seven, the image of Henry now clashes with the ruthless criminal he once was, who operated alongside Smith and a gang which he said wouldn’t hesitate to kill. Henry engaged in violence regularly and has shot, stabbed and bashed people senseless.

Henry has opened up to Gary Jubelin for the I Catch Killers podcast to tell his life story covering an era which has long fascinated Sydney, when crooks and cops would gather at the same pubs and a few dollars in the right hand went a long way.

He readily admits that his was a world of continual violence, where he often started the car with a broom handle. And what made him even more dangerous was that he didn’t fear death.

“I’ve had fights in the prison system where I’ve just walked up to a bloke. I knew he was a willing bloke too, and I’d just pull out a knife, throw it on the ground and say, ‘here’s a knife for you, I’ve got one, now let’s fight to the death. Best man wins, mate.’ He never had a taker.

As to why an ex-cop like Jubelin wanted to go head-to-head with one of Sydney’s most feared figures, he says it was important these stories were told before they were lost.

“People are fascinated by the life Graham lived, he was a gangster in the truest sense, a feared underworld standover man,” Jubelin says.

“Through Graham I want to show people how treacherous and violent the world really is. There is nothing glamorous about the lifestyle, just look at all the attempts of his life. Graham’s story is not glorifying crime, if anything it’s about warning people not to follow in his footsteps.

“Graham’s story is part of Sydney’s dark history – a time of corruption. The gangsters had police, politicians and officers of the court on the payroll. It seems like a bygone era, but if it is swept under the carpet as if it never existed it could flourish again. “

Henry himself remains regretful about some incidents and unrepentant on others. It was the code he lived by, the law of the streets and everyone knew the rules.

A VIOLENT UPBRINGING

Henry only knew a life of violence as a child, something he believes played a role in his descent into the criminal underworld.

“I lived in gutters, I lived in friggin drains, toilet blocks just to keep away from it all,” Henry recalls. “But in the end I had to go and protect my mother and I guess it just made me the bloke I am today.”

Growing up in suburban Epping in the 1950s and 60s Henry’s WWII veteran father was a violent alcoholic who bashed his mother regularly.

“He was a lunatic who flogged my mother all my life,” Henry says.

“I remember the police turning up at the house and they just used to call him outside and tell him, ‘Mate, just keep it down.’ And I got a big hatred to the police for that. I thought you are supposed to be out there protecting people and you’re coming around condoning what’s going on in this house.”

Henry says he learnt to box from the age of 13 to protect himself and his mother and would often be trading punches with his father on the front lawn of their home.

One night at the age of 16 Henry says he was ready to kill his father after his mother suffered another brutal beating and was hiding under the house so her son couldn’t see her.

“I dragged him out of bed and punched the living daylights out of him,” he says before grabbing a two-pronged barbecue fork and stabbing him.

“My mother pulled me off him and I thought, ‘what did you do that for?’.

“I just wanted to finish him. If no-one stopped me I would have killed him.”

Henry said he had no doubt that much of his anger stemmed from the household he grew up in.

“It certainly made me an angry person. You know what I mean? Deep down inside, I was like a bit of a boiling cauldron deep inside. I could be pretty calm on the outside. Yeah, but I have that thing in me, that, you know, my rage might build up over months and months, and then I’ll let it out, you know what I mean?”

Henry would later learn that the man he thought was his father was in fact his stepfather and instead and is believed to be the product of his mother’s affair with a local Indigenous man. He says making a connection with the local Indigenous community where he now lives has been one of the joys of recent years.

I WAS A PIMP BY 16

Given the dysfunctional, violent household he grew up in, it’s no surprise that Henry found himself running foul of the law from a young age.

From small-time burglaries, Henry graduated to stick-ups by his mid-teens. He’d committed to life as a gangster by then, although there had been dreams of a life as a singer or a boxer.

Before he was even a fully grown man, Henry was already operating a small, mobile prostitution ring.

“We had a little truck at the back of the pub we used to bring around and (it) had a bed bolted in it. We used to have this eggtimer in the front, in the brothels in the old days they used to only give you three minutes and once the egg timer run out they’d turn it upside down and you’d have to pay again,” Henry says.

“So we got this van and started going down to the back of the pub and picking up blokes when they were coming out … and then put them in the van and drove them around the block and keeping them in there. Some of them would stay in for an hour. We just did it on the sly.”

When Henry wasn’t involved in stick-ups or mobile brothels he was causing wars between tow truck groups. Henry and his crew would then be employed to execute a payback despite the fact that they were the ones who had committed the original crime.

By this stage Henry felt that he had no control over what his life was to become, that the world of crime had picked him.

“I sort of knew from a teenager where I was going. It was like I thought my life was a movie, I was playing some role, I was given the role I was in and I was going to play it well.

“That’s where I sort of headed and I just pushed myself in that direction all the time. Then you end up in prison and you meet some other scallywags and things start to escalate from there.”

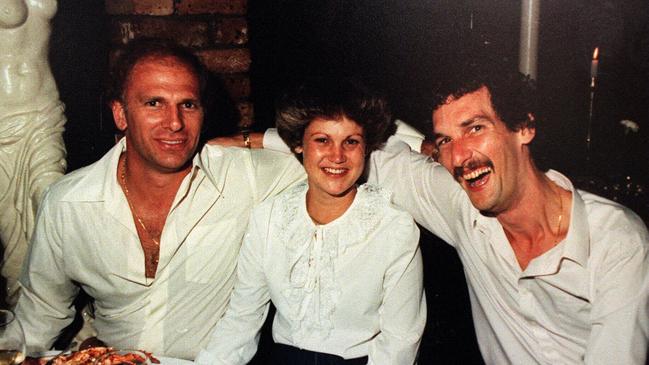

NEDDY AND ME

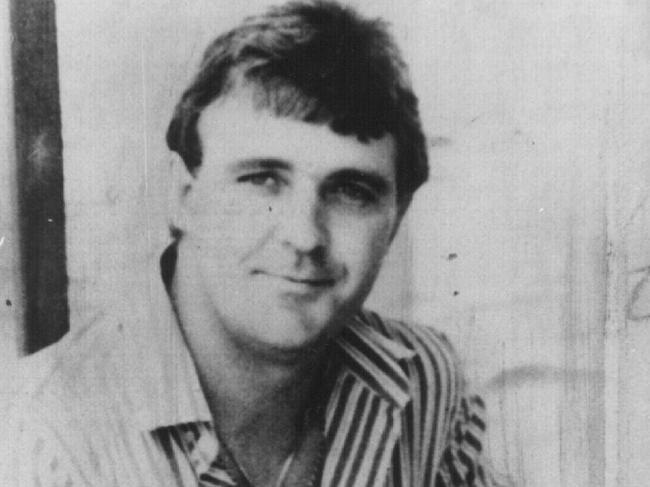

As far as Sydney underworld figures go, regardless of the era, there were few bigger names than Arthur Stanley “Neddy” Smith.

A brutal, violent thug, jailed for rape and eventually murder, an armed robber and drug trafficker he was also a police informant who worked hand in glove with corrupt cop Roger Rogerson in the 70s and 80s.

Smith and Henry ran the crew that made millions from their criminal activity. They had met while both spent time in Parramatta Jail in the early 70s and forged one of the most feared partnerships in Sydney when they teamed up when their sentences were finished having reacquainted at the Governor Burke Hotel on Parramatta Road.

“He was a towering big bloke. Had a reputation, you know, he could fight like a thrashing machine. A monster of a man, a big boy. He would have been in those days, 17-18 stone, six foot four and a half, a big boy. You know, big shoulders, big head, big teeth.

“The bloke had charisma. He could have been anything … but he had this filthy, treacherous nature.”

It was Henry who had suggested their first armed robbery together while driving near the Broadway Hotel in Smith’s BMW.

“‘Just remember’, (Smith) said, ‘if you roll on me, I’ll kill you’. ‘Well, that’s a double edged sword mate,’ I said, ‘cause I’ll kill you, too.’ And that’s how we virtually started off our relationship from there.

“Anyway, we did what we were going to do and come away with it. And then he said to me a couple of months later, ‘Listen, I can virtually do what I like. I’ve got a copper sweet. I just give him a little bit of a duke and I went, ‘well, that’s all right.’”

The copper was Rogerson and he had given them the famed “green light”.

Smith and Henry played a central role in the Sydney underworld of the 70s and 80s, clashing with rival gangs of which the main ones were those operated by Barry McCann and another by George Freeman and Lenny McPherson.

Drugs, armed hold-ups, standover tactics, illegal gambling were all part of the stock in trade for these gangsters. Hits were common with Christopher Flannery, the city’s most infamous gun for hire.

“They are worth spit,” says Henry. “I don’t like hired killers … And I’ve met ‘em all.”

THE GREEN LIGHT

Henry says there was a distinct difference between the gangs of 70s and 80s and the bikie gangs which dominate the criminal scene today. “

“The gangs in our days, they didn’t consist of big groups,” Henry recalls. “They didn’t need big groups because we had what organised crime really is – we had the power of the police, we had magistrates on side, judges on side.

“We could get to politicians … It was like a giant octopus with tentacles stretching out into every part of society gathering information of someone so you could use against them or and so we had so many connections. A lot of my connections come through (Fred) “Paddles” Anderson who was really the Mr Big of Sydney. And then Lenny (McPherson) sort of took the reins and he stood back.

“But he did plenty of favours for me over the years with judges and things like that, got me good sentences, got me out of jail early.”

Henry benefited from corrupt politician Rex “Buckets” Jackson’s scheme to release prisoners early, which enabled to cut short a sentence so he could be at home with his wife who had endometriosis at the time.

“Rex Jackson was a real bad gambler and once they’re a gambler you’ve got ‘em.”

Henry is matter-of-fact about the way the underworld operated and the freedom the “green light” provided.

“And that’s just how it operates, you know, and you just got to use all those advantages to the best that you can,” Henry says.

“It was the same with the police. You know, we could get pinched for having a real bad fight and someone got hurt really badly.

“They (the police) would meet us at the pub or something and they’d say we got to pay the boss of Balmain five grand and it’s going to cost you another 10 on top of that. So we’d just pay him and, you know, give him the money and we’d walk away without any charges and that was the green light.”

A DAY IN THE LIFE

Unsurprisingly the day-to-day life of a gangster was not your typical nine to five.

“We might have committed a robbery by 8 o’clock in the morning, then it was back, count up the (money) and go and get changed.”

“I always liked to be active, I had to be doing something. If there was nothing on and say money was coming in easy from, say, some drugs or something that week (but) we didn’t only do that.

“We did drugs, we did armed robberies, dug tunnels, we stole safes. We did all sorts of tricks.”

At other times he would do reconnaissance missions and start planning upcoming jobs.

“I might drive out to Lane Cove where the armoured trucks used to leave from. I’d follow them all day doing my homework and I’d look at the tins. I could nearly tell by the (way they) carried the tins what was in ’em. That’s about 30 grand, that’s 50, probably 100 in there, 200, 500.

“If they didn’t have big ones you’d follow another one.”

Although there is a report Smith and Henry once beat a club security officer so badly he lost sight in an eye, Henry would beg to differ.

“Never, ever, ever on any robberies I ever organised, and I was the one that organised them, did we hurt one soul.”

Henry and Smith and his crew would often be found at the Star Hotel or Iron Duke in Alexandria, maybe discussing their next job or just drinking heavily.

“I’ve even been in pubs and the police have pulled out their guns and started shooting glasses off (the bar), so did we,” Henry says.

They were gangster pubs, the Iron Duke, in particular had a notorious reputation as the home of the “Toecutters”, where gangsters would cut the toes off fellow crooks in the pub’s cellar in pursuit of cash.

“They were the lowlifes of the crime world … when you’re skimming them out of greed, they’re the scumbags, they got no principles.”

Not that he’d be found there every day. Henry, as had Smith, moved up the Central Coast to try to have a normal family life away from the crime centre of Sydney.

Henry said during this time, he also lived the life of a doting father who was able to switch off the violent life he led as an underworld gangster when he reached the front door.

“I’d drive up there round the lake and say ‘Thank Christ I’m here’. I always spent time with my family.

“I’ve been married 48 years, the same woman. And you know, we all have our ups and downs in our lives, marriages, we have had some shit times and we’ve had some great times, you know? But on the whole, I’ve got a great family, great family life, got a great wife, solid as a rock. And as I said, I never told her anything anyway.”

NEDDY THE FRAUD

As Henry and Smith committed more crimes and spent time together, it emerged to Henry that the perception of feared gangster Smith was not the reality.

“He used to say to me, ‘when I kill someone, I get lucky’.” Henry says.

“Well, I can tell you this honestly. And in almost 10 years, I ran with him. Ned never killed anybody … Ned’s always the back seat man.

“So he had this massive reputation that he killed all these people like (drug dealer) Lewton Shu. Yes he was there but he was behind the goalposts all the time.

“They started to call Foreshore Drive at Botany Neddy Smith Drive because bodies kept on popping up there, Harvey Jones, Bruce Sandery, there’s probably another 20 out there.”

Henry says even he witnessed Smith’s form for not wanting to be the one that pulled the trigger after he fled a payback operation between rival gangs.

Smith had been shot at coming out of the Quarryman’s Hotel in Pyrmont when he was fired at by rival Barry McCann’s gang. Henry retaliated by shooting McCann gang member Terry Ball twice in the head.

“I walked up and had a look through the window. I said, ‘Well he’s right there’. They’re all playing cards, about five of them.

“As we get up the steps, I look back and he took off on me. He ran up the street. I couldn’t believe it. I just walked in and went ‘whack, whack’.”

Ball survived.

Even the murder of Harvey Jones that Smith served a life sentence for, Henry is adamant he was not responsible and only bragged that he did it. “Ned never killed him, Ned was back at the Star Hotel.”

MR RENT-A-KILL

Henry’s and Smith’s relationship had started to deteriorate by the 80s. He was still working jobs with him but whatever minimal trust there is between gangsters had eroded.

“A couple of sneaky things started happening. When I went and shot someone on his behalf who tried to kill him I thought to myself this bloke’s so over exaggerated like his reputation … (He) was always taking back seats. He’d rather manipulate people and, you know, like that treachery in him and get others to do his work for him.”

When Smith brought Christopher Flannery, the infamous “Mr Rent-a-Kill” who would later disappear without trace, into the company it drew the ire of Henry and nearly ended in a deadly confrontation.

“He started getting around in the company and then he started creating havoc. He met with a copper one day, one of the coppers we had had sweet, and pulled a gun on him (and) stuck it in his head and said, ‘You know, you’re not a koala bear. I’ll put one in your fucking head’. And I said, ‘Jesus Christ. This bloke is just gonna bring drama.’”

Henry said things started to unravel and it got to the point where Smith and Flannery hatched a plan to execute him in a Redfern unit.

“Chris is sitting on the lounge and has his hand near a pillow … Next minute Ned goes ‘I got to go somewhere’, he’s never around, he’s always behind the goalposts.

Having grabbed a cup of coffee from the kitchen Henry says he asked Flannery where Smith and other crew members had disappeared to.

“He said, ‘I don’t know mate’ and started to move his hands and as he moved his hands (I) pounced on him and underneath the pillow is a gun with a silencer in it. I shot that to the end of the lounge so he couldn’t reach it and I jammed mine straight in his mouth and I’m going off, ‘you, dirty, filthy grub’.

He said there was a knock on the door and a woman entered the room as he was threatening Flannery which Henry said forced him to flee the building.

It wasn’t all one-way traffic though when it came assassination attempts and Henry, who claimed Smith tried to have him killed at least four times, reveals very matter of factly that he tried to ‘knock’ Smith when their relationship had soured.

His own attempt at Smith’s life outside the Three Weeds Hotel in Rozelle foiled when a police van drove by as he was about to shoot him.

“I lay in the garden bed with a gun on my chest (and) as soon as touched the door, hopped into the car that was the end of him, I was just going to unload on him.

“Just as he was about to open the door the police pulled up on the corner and yelled out to him, ‘Hey Ned, where are you going to?’

“I had to lay back down, I was just on my way up to get on with it and I thought they could hear my heart beat, the adrenaline was running that fast.”

Henry did not give up the chase there and followed him to a nightclub in Balmain but the attempt was thwarted by the human shield Smith had put around him as he exited the club.

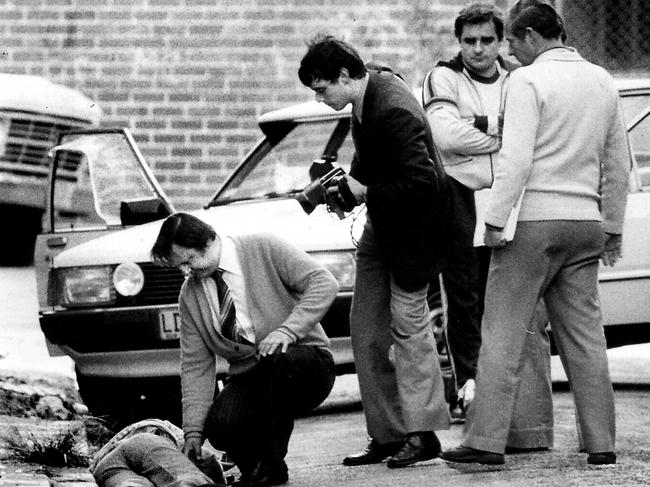

THE COPS TRIED TO KILL ME

Danger always lurked, it was a way of life for a Sydney gangster. And he says it was not just other criminals that wanted Henry dead. In 20 attempts on his life the day the police opened fire on him in North Sydney was the closest he ever came to death.

Having done a nine-month stretch for possession of a gun, Henry said he was desperate on his release and organised for a drug deal – a pound of heroin for $90,000 – that was to go down on June 12, 1981.

Sitting in his car with the engine running in Mount St, Henry twigged that he had been set-up. His fellow dealer was in fact an undercover cop who bolted from the scene.

“(I) went to whack the car into gear (but) police blocked the road. Cars come from everywhere, a truck and coppers run from doorways, out of shops, and next minute I just knew by the way the cops were standing there (they were going to shoot me), there was a lot of cops in the front of the car with shotguns all aimed at me.

“I put me hand over me eyes and I shot myself back across the seat and the gun went boom straight through the top of my scalp.

“So they took me to the Royal North Shore Hospital. They took out pellets out of me head, glass and crap out of me eyes from the windscreen.

“And then I was taken to Long Bay hospital and put in there. Anyway, I did my time over it.”

GALLERY: THE BIG WIGS OF SYDNEY’S UNDERWORLD IN THE 80S

THE NIGHT I STABBED A COP

There was an unwritten agreement in the underworld that cops were untouchable.

It was a rule that Henry was to break, much to his regret, the night he stabbed police prosecutor Mal Spence.

Having drunk heavily all day he spied Spence in the Lord Wolseley Hotel in Ultimo. Henry had accused Spence of calling him a dog to other crooks, a huge insult to those in the criminal underworld.

Henry demanded Spence join him in the alley behind the pub and it marked the beginning of the end of his days as one of Sydney’s most notorious gangsters.

Henry claims Spence could not even get a sorry out of his mouth before he left-hooked him and he dropped to the ground.

“I wanted him to have a crack at me. Anyway he got up and went into this big sook mode. ‘(He said) Mate, I was wrong, I was out of school’,” Henry says.

“I just pulled it (the knife) straight out of my pocket and I went whack straight into his guts and then I plunged it straight into his neck.”

Spence escaped death by a centimetre and meant Henry also avoided a lifetime in jail as a cop killer. Henry spent six of his eight year sentence behind bars.

“I just regret it all together, I regret the stupidity of it all, I should have just knocked him down and give him a touch up for what he said. The next morning I just went ‘oh, what have I done?’ I knew straight away that was the end of me, my green light days were gonski.”

“I certainly regretted doing that. I didn’t mind that Malcolm before that but it’s a stupid thing for him to have said and he should have known better.”

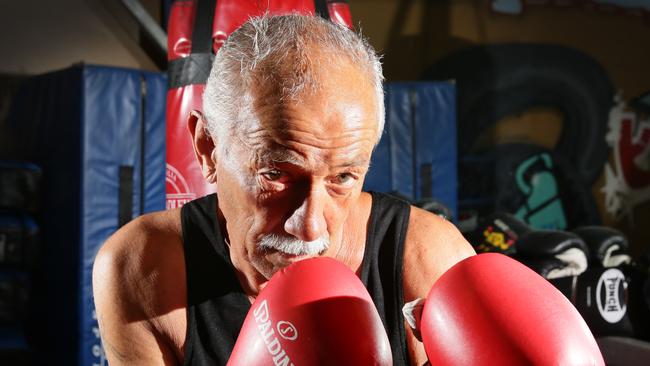

HENRY’S LUCKY LIFE

Henry’s reputation precedes him. He was a notorious gangster and he doesn’t hide from the violence or the life of crime he lived.

A violent upbringing only partly explains why Henry chose the path he followed.

“I think I was just wired for it, I could handle all the bullshit, handle the pressure,” he says.

“I walked into the lion’s den many times when they were ready to put me down.”

He believes he has had a blessed life, the mere fact that he is still standing and can tell his story testament to that.

Rather than drinking beers at the Iron Duke and planning the next armed stick-up, Henry spends his days with family and a growing army of grandchildren.

A hard-nosed crook who suffers from anxiety is hard to imagine but Henry said he turned to meditation to help with his mental health as he tried to navigate a path on the straight and narrow after 35 years in the underworld.

“When I give it away, I was struggling, it was like a footballer giving up his career you know what I mean.”

And when he reflects on his life he said he knows its part of Sydney’s sordid criminal history and holds a fascination for true crime junkies but adds that it’s one that should be avoided at all costs.

“I wouldn’t recommend this life to anybody, it’s just a world of snakes and rats. The odd good bloke here and there, they’re hard to find.”

And what should the rest of the world make of Henry, someone who has lived as a villain for most of his life. Henry himself isn’t looking for forgiveness, he says owns his past.

Jubelin says that Henry is a decent human being.

“I can’t condone the crimes that Graham has been involved in, nor would he expect me too. He had a tough upbringing, but he doesn’t use that as an excuse to justify the life he has lived,” Gary Jubelin says.

“He lived by a code that was respected in the world he inhabited. I don’t agree with what he has done, but I can respect him for being true to that code. He now appears to have values that are more closely aligned to my own values. I like people that are true to themselves and Graham is certainly that.”

EPISODE 1 OF GARY JUBELINS’S FOUR PART INTERVIEW WITH GRAHAM HENRY IS OUT ON MONDAY, MARCH 28.