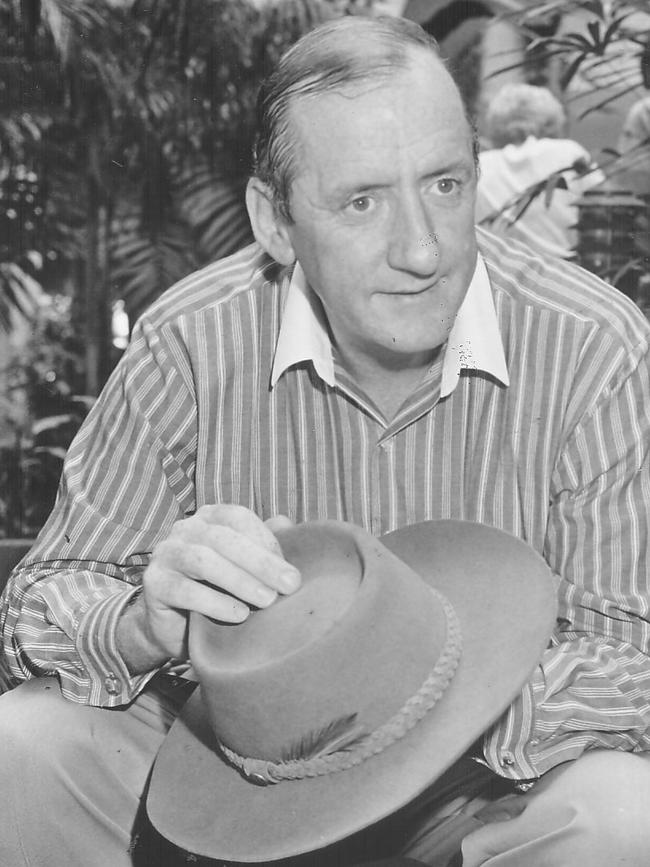

Former deputy PM Tim Fischer feared Agent Orange exposure before death, aged 73

War wounds nearly killed Tim Fischer in Vietnam, but it was Agent Orange which claimed him in the end as Australia mourns a political giant and war hero following his death, aged 73.

NSW

Don't miss out on the headlines from NSW. Followed categories will be added to My News.

War wounds nearly killed Tim Fischer in Vietnam but it was Agent Orange which claimed him in the end.

In 1966 Mr Fischer was conscripted into the Australian Army and served in Vietnam.

As a platoon commander based at Nui Dat, he almost died in Operation Fire Support Base Coral near the southern exit to the Ho Chi Minh Trail in 1968.

Then-Lieutenant Fischer was hit by shrapnel from a rocket during a midnight attack by North Vietnamese regulars.

He suffered a shoulder injury, but was saved by his flak jacket when another piece of shrapnel hit him in a chest. He was evacuated by helicopter the next morning.

Following his cancer diagnosis in 2018, Fischer theorised his exposure to Agent Orange during the conflict may have caused his health problems.

After serving in Vietnam he took up farming at Boree Creek in the Riverina and became an active member of the Country Party.

It was the beginning of a lengthy political career, first representing the seats of Sturt then Murray in NSW Legislative Assembly from 1971 to 1984, then as the federal MP for Farrer, before becoming leader of the National Party in 1990 and deputy prime minister in the Howard Government in 1996.

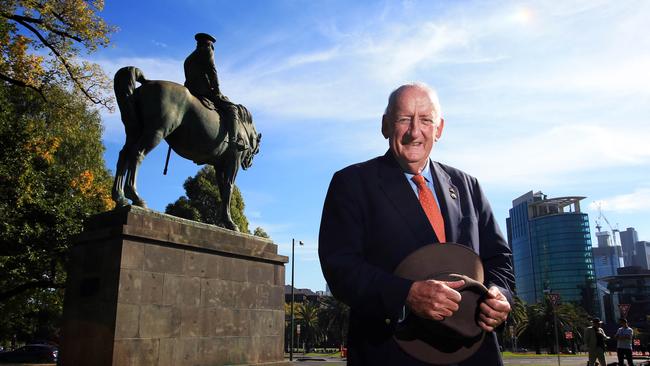

When Tim Fischer announced he was stepping down as deputy prime minister in 1999 he was met with a rare public outpouring of goodwill and appreciation from both sides of politics.

Citing a “convergence of certain political and personal factors” the devout Catholic, tie-collecting, train enthusiast had decided he wanted to spend more time with his wife Judy Brewer and sons Dominic and Harrison.

At the time then-Prime Minister John Howard described Mr Fischer as the “epitome of loyalty and decency”.

“No coalition leader could have had a better friend, a firmer ally or a more dependable quality in difficult times that I’ve had in you,” he said.

His passing two decades later at the age of 73 after battling acute myeloid leukaemia will undoubtedly be met with further admiration and praise from across the political divide.

Mr Fischer leaves behind an impressive legacy, most notably as the person who steered the Nationals party room through the implementation of the 1996 National Firearms Agreement in the wake of the Port Arthur massacre.

He was stoic in the face of personal attacks, including most infamously in the Queensland town of Gympie, where pro-gun protesters hung an effigy of him in a noose outside the Civic Centre with a sign saying “Tim Fischer: Traitor”.

Former editor of the Gympie Times Michael Roser described it as one of the “saddest sights” he had ever seen.

Yet Mr Fischer bravely fronted the packed Gympie theatre, battling constant interjections from the pro-gun crowd, later describing the meeting as one of the hardest things he’d ever done.

He continued to influence gun debate in Australia and abroad, co-signing an open letter to voters in the NSW state seats of Cootamundra and Murray in 2017, urging them not to support the Shooters Party as it would “fundamentally weaken” existing firearms laws.

Reflecting on his role in Australia’s gun reform in an interview with US media that same year, Mr Fischer said he firmly believed he had made the “correct call”.

“(I) gained majority support, even in country electorates,” he said.

“I defended farmers, hunters, and Olympic shooters having the right kind of weapon as they go about their work, recreation and sport.

“I’m not anti-gun. I’m anti automatics and semiautomatics dominating the suburbs.”

Timothy Andrew Fischer, AC was born on May 3, 1946 in Lockhart, a small agricultural town in south west NSW.

When current Deputy Prime Minister Michael McCormack visited Lockhart in May to open a gallery featuring artefacts from Mr Fischer’s political career, he described his predecessor as beloved by everyone.

“There’s a couple of initials after Tim Fischer’s name and it’s AC,” Mr McCormack said.

“Now that is the highest honour that anyone in Australia can achieve but AC to me for Tim Fischer stands for ‘a champion,’ it stands for ‘a colossus,’ it stands for ‘a character’.

“He’s one of those rare breeds of people who everybody loves, they know who Tim Fischer is, they know what he stood for, what he still stands for till this day.”

Mr Fischer stood out among his parliamentary colleagues with his Akubra hat — worn both indoors and out — genial personality and staccato speaking style.

After his 1999 announcement then-Labor leader Kim Beazley recalled a time when the pair were in India and local officials had asked why Fischer wore a hat inside at night.

“I said it was an ancient Australian religious custom,” Mr Beazley joked.

One of the key personal factors behind Mr Fischer’s resignation was his then five-year-old son Harrison’s diagnosis with autism.

It was only after his son’s diagnosis that he realised he may have also had a mild form of autism himself.

“In hindsight, I came to realise that I have always had a very mild autism spectrum disorder that went undiagnosed for most of life,” he said in 2012.

“By dint of education, army, family and faith I managed to sublimate the condition. That doesn’t mean it goes away, just that you learn to cope with it.”

Mr Fischer was a strong advocate and supporter of Autism NSW.

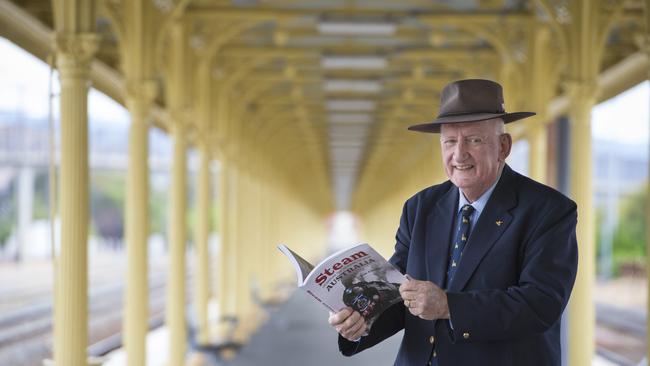

He had a great enthusiasm for trains, amassing an extensive collection of memorabilia and penning several books on the subject.

After retiring from politics he was special rail envoy to Adelaide and Darwin, travelling on the first freight train and first Ghan passenger train to Darwin in 2004.

Years later he briefly hosted an ABC podcast called The Great Train Show.

Fischer’s interest in trains was sparked at a young age when he and his father would drive into Boree Creek to meet the train every Monday night to get a copy of the Sydney Sunday morning newspapers.

“As a young kid, to buy the Sunday newspaper with comics (there was a) great level of excitement as (the train) hurled down the line … and that evoked my initial interest,” Fischer said.

Mr Fischer also kept every necktie he’s ever owned — from his school days at Xavier College in Melbourne through to his service as Ambassador to the Holy See between 2009 and 2012.

He endeavoured to continue his famously busy schedule as he battled the cancer, even getting leave from hospital for a few hours to launch his latest book on trains last year.

T