Deputy PM Michael McCormack vows to put family first as he tries to unite a fractured party

AUSTRALIA’S new deputy Prime Minister, who says anti-AIDS ads in the 1980s fuelled his homophobia, says he has offered to be master of ceremonies at a gay relative’s wedding.

NSW

Don't miss out on the headlines from NSW. Followed categories will be added to My News.

AUSTRALIA’S new Deputy Prime Minister Michael McCormack says he is a changed man.

The former newspaper editor, who last week replaced Barnaby Joyce as National Party leader, has spent years defending a controversial article he penned in 1993 blaming homosexuals for spreading AIDS.

Speaking to The Sunday Telegraph, Mr McCormack said: “I have changed,” instead blaming the iconic Grim Reaper ads for fuelling his beliefs.

“We were being bombarded with government ads warning about the dangers of AIDS. It was scaremongering,” he said in defence of his controversial piece.

“Community attitudes were different and they’ve changed.”

In a sign of his shifting views, the Deputy PM has even offered to MC a same-sex wedding for a gay relative who plans to tie the knot.

Mr McCormack will have a huge task ahead of him as he tries to unite his splintered party. In the past 18 months the junior Coalition partner has gone from election-winning machine to national laughing stock.

The citizenship scandals saw then-leader Barnaby Joyce and his deputy Fiona Nash disqualified from Parliament.

A group of Nationals MPs then launched a parliamentary revolt, forcing Malcolm Turnbull to adopt a banking royal commission or risk losing support.

The conservative party then faced further humiliation when Mr Joyce stood down following the collapse of his marriage and the pending arrival of a new baby with a former staffer.

Mr McCormack admits it has been one of the most “trying times in the party’s history”.

“It has been difficult, there is no question about that,” he said.

“No one can take anything back that they have said or done; it’s time to draw a line under it and move on ... we will be a unified team.”

While Mr Joyce has refused to rule out a comeback, Mr McCormack poured cold water on the idea, instead rewarding backers — Darren Chester and Keith Pitt — with promotions in the latest reshuffle.

“I think that’s getting a bit too far ahead of ourselves,” Mr McCormack said when asked whether there would be room for Mr Joyce on the frontbench.

Mr McCormack knows the damage a career in politics can have on families. He has watched Mr Joyce’s political and personal life implode following an affair with former staffer Vicki Campion.

Boozy nights away from home and a busy work schedule have destroyed countless political partnerships, but Mr McCormack, a teetotaller, says he will always prioritise his family.

“Once politics goes, I still want to have my wife and children,” Mr McCormack said.

“At the end of the day, you might be the Deputy Prime Minister, you might have a very important office, but you are still a husband, you are still a dad and you have to make time for family.”

When the NSW MP first arrived in Canberra in 2010, speaker Harry Jenkins offered frank advice to the cohort of Labor and Coalition MPs embarking on a career in federal politics. “We were told the divorce rate among politicians is somewhere around 80 per cent and I certainly didn’t want that to happen,” Mr McCormack said.

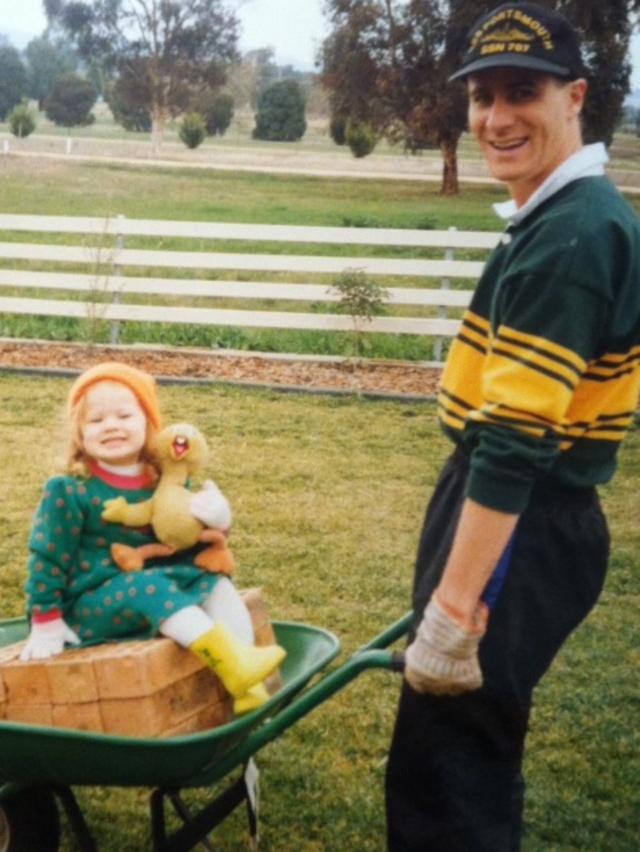

For the Turnbull government, which is desperately looking to avoid further scandal, Mr McCormack is considered a safe pair of hands. The 53-year-old has been married to wife Catherine for 31 years. The pair started dating when he was just 18 and he would collect her from high school in his blue Holden Gemini. They have three children — Nicholas, Georgina and Alexander.

But in political circles, his rise to Deputy PM has been described as his “Steven Bradbury moment”.

Reminiscent of the Aussie speed skater who clinched Olympic gold in 2002 when he was the only man left standing at the finish line, Mr McCormack — a relatively unknown MP from Wagga Wagga — now holds the second highest job in Australia.

He is viewed by some detractors as ill-prepared for office, but it was a trip to Canberra with Henschke Primary School in 1976 that first sparked his drive towards political leadership.

At just 12, McCormack jumped off the bus at Old Parliament House, where then-prime minister Malcolm Fraser was addressing the media. “I remember thinking, ‘gee, that’d be a pretty good job,’ ” he said.