Dawn Fraser: From Olympic hero to personal tragedy

Olympic hero Dawn Fraser has survived being raped twice, domestic abuse, depression and the tragic deaths of her parents. The four-time gold medal winner has had immense highs and deep lows, and at 83 still dominates on the water.

NSW

Don't miss out on the headlines from NSW. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Dawn Fraser is sharing the turmeric recipe she credits with halting the arthritis in her fingers. It’s an elaborate process, involving smashing, cooking and drying her homegrown turmeric before it’s mixed with pepper and a few other spices.

Every morning, she sprinkles the concoction on top of her Weetbix, banana and honey.

She spreads her 83-year-old fingers on the table as proof of the wonders of the spice. “I couldn’t bend that one before,” Fraser says, twiddling her middle finger back and forth.

Turmeric. Just one more spice added to the life of this Australian icon.

For three hours now, we’ve been delving into the stuff that made “Our Dawn” – the ingredients of a life so big, so complicated, so filled with triumph and trauma.

“I’ve done everything, tried everything,” she says, her eyes twinkling as if she’s just nicked an Olympic flag in the dead of a Tokyo night.

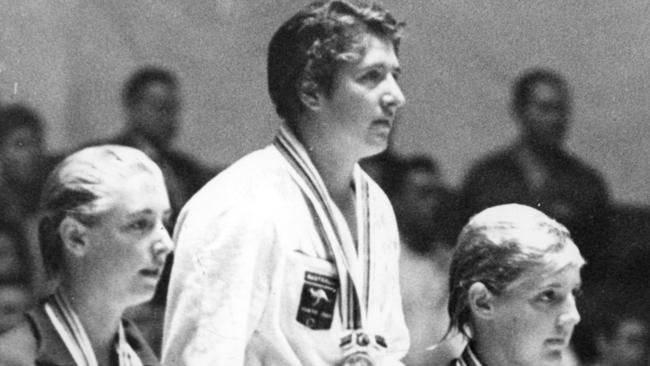

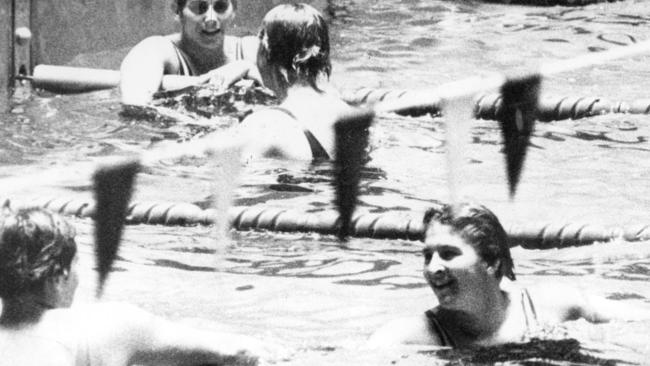

Winning one Olympic gold medal would be enough for most. Fraser won four but, more impressively, three of them were in the same event – the 100m freestyle – in three consecutive Olympics.

She was the first swimmer of either gender to chalk up that record, in Tokyo 1964. Only two others have done it since.

Big win, legendary celebration. As the Tokyo games drew to a close, Fraser bounded into the night with two others, hoicking one of them up flagpoles near the Imperial Palace to souvenir Olympic flags.

Police came, she ran, twisted her ankle, was cornered by police, grabbed a bike and pedalled off before being nabbed.

At the police station, the superintendent didn’t believe she was the world-conquering Fraser. “No, Dawn Fraser not do this,” she recalls him saying. “Oh, yes,” she told him, “Dawn Fraser would do this.”

She was the Aussie battler with a freakish skill. The larrikin. The rebel.

But the story of Dawn Fraser takes on another dimension when you step outside her swimming career. Beyond the accolades and hype, she’s everywoman.

She’s lived through domestic violence, divorce and single-motherhood. She’s been so depressed she was a borderline alcoholic, and contemplated suicide. She’s been raped, twice, and had an abortion. She’s had – and hidden – lesbian relationships.

As the country grapples with the way women are treated – still – Fraser admits she thought attitudes towards women would have improved by now. She’s disgusted by the rape and sexual harassment allegations coming out of Canberra, and fires up when talk turns to domestic violence.

“I hate domestic violence because of what I went through and I had to hold that in for quite a number of years before I could let it go,” she says.

Fraser’s a survivor. Life has tempered the rebelliousness but there’s a steeliness about her. At times she’s guarded, then surprisingly candid – even cheeky. “Every time someone says ‘crack of dawn’, it gets me,” she jokes. She’s a curious mix of the homespun and the worldly, conservative and progressive.

But still a little unconventional. If you see a jet ski-riding octogenarian zipping about on the Noosa River, chances are it’s Fraser.

She left Sydney 12 years ago to live with her daughter, Dawn-Lorraine, now 55, and grandson, Jackson, 17.

Fraser’s happy with the Sunshine Coast move, and thrilled the Olympic Games look set to come to Queensland in 2032. “I think it’s bloody fantastic,” she says. In fact, she wants a job. She’s even got one in mind.

OUR DAWN

The dog walker is lurking near the picnic shed on the riverbank at Noosaville, her eyes latched on Fraser. As the rain we’re sheltering from gets heavier, the woman with the staffy seizes her chance.

“We’ll just get out of this rain,” she says, shuffling under the roof.

Fraser apologises that she can’t pat the dog because she has german shepherds at home that won’t appreciate the smell of another dog. Bronson is the fifth shepherd Fraser has owned and she’s now training No 6, Coco, just 12 weeks old.

The woman decides to show Fraser a few of her dog’s tricks and Fraser indulges her as Ted high-fives and shakes. It’s not unusual, says Fraser, once they’ve wandered off, for strangers to want a moment or two with her.

It’s that familiarity thing. We all know Our Dawn. She’s the working-class girl from the Sydney suburb of Balmain, who as a kid was a runner for notorious underworld figure Lenny McPherson, collecting bets for the now dead SP bookmaker.

She’s the scallywag who stared down the elitist swimming establishment and became the golden girl.

She’s the woman who the nation’s heart went out to when, in 1964, about eight months before her star turn in Tokyo as a 27-year-old, she crashed her car, killing her mother, Rose.

Fraser woke up in hospital with cracked vertebrae and torn ligaments in her knees, to hear nurses saying her mother was dead on arrival.

The accident – Fraser’s car hit a ute parked on a kerb at night – is the worst thing that ever happened to her, she says. A coroner declared it a tragic accident.

Fraser rarely talks about it. But two years ago, at a camp for swimmers at a vineyard in South Australia, the MC asked all guests to tell a story about their lives.

“I burst out that I was driving the car that killed my mother,” she says. “Everyone burst into tears and I cried with them. It got me over some sort of hurdle. I’d just locked it up inside of me.”

The more you talk with Fraser, the more it becomes obvious that this woman born between two world wars has lived by the “soldier on” mentality. Pull yourself up by the bootstraps and move on. Counselling wasn’t a thing back then, and she hasn’t sought it since.

When I ask if the recent events in Canberra have triggered flashbacks of the sexual assaults she endured, Fraser makes a downward motion with the palm of her hand. “It’s in the past and I don’t live in the past,” she says.

Still, the present can’t be avoided. Swirling about in the national psyche are allegations of the rape of Liberal Party parliamentary staffer, Brittany Higgins, the historical rape claims against now former attorney-general Christian Porter, and the lewd acts by Coalition staffers on female MPs’ desks.

“It’s terrible, just terrible,” Fraser says. “I never thought that it would ever happen in parliament, or in their offices. But it does; it happens everywhere.”

It first happened to Fraser when she was in her early 20s. A man she met at a party took her back to her hotel room while she was drunk, and “took advantage of me”.

Even now, she blames herself: she shouldn’t have got so drunk. I tell her it wasn’t her fault. “Yes, but Dad would turn over in his grave if he’d known I’d got that drunk.” The conditioning of our times.

Fraser was a virgin. And she became pregnant. The only person she told was her coach, Harry Gallagher (who died recently). She decided to have an abortion and Gallagher organised it. Months later, her Scottish-born father, Kenneth, died from lung cancer.

“That was one of the most horrific times of my life,” Fraser says. “So horrific I put it in the back of my mind and try not to think about it.”

Ten years later, in 1971, she was at the Riverview pub at Balmain – a hotel she would later run for five years – when a friend phoned.

“Fat Face” was a good mate, one of the “roughies” from the underworld who used to frequent the pub. He was on a ship down at the docks, drinking with some sailors. Could Fraser bring a carton of beer?

She did, and when Fat Face ducked to the toilet, a Polish sailor shut the heavy door, locking in Fraser.

“It was terrifying,” she says. He told her to get undressed. She reached for a bottle opener and tried to fight back. He held a knife to her throat and raped her.

Fraser was cowering in the corner of the cabin as the sailor drank scotch when the police arrived. The ordeal had lasted almost four hours.

“If it hadn’t been for (the police arriving after Fat Face raised the alarm), I don’t know where I would have ended up,” she says. “Probably at the bottom of the ocean.”

The sailor was charged; Fraser went to hospital. But the case did not make it past committal. Insufficient evidence to go to trial: her clothes weren’t ripped, the cabin wasn’t wrecked.

Even Dawn Fraser couldn’t get a rape charge to stick in those days.

But there may have been some rough justice dispensed by her Balmain friends. “It was mentioned to me that ‘we’ll get him’. That’s all that was said,” Fraser recalls. “I said, ‘All right – I don’t want to know any more’.”

The rape destroyed her trust. She’d recoil when touched unexpectedly. “You don’t trust; you’ve got to get that trust back in you. And that takes a while.”

The Canberra situation has raised more questions for Fraser than she has answers. Is it upbringing? Is it drugs? Is it the work atmosphere?

Then she says: “I think the word is respect. Not just men have to respect females; females have to respect men. I hope we’re in a changing period. If not, we should be.”

But not through marches or rallies. “I don’t like protests,” she says. “They disrupt a lot of people”.

She did not support the march on parliament by women calling for change, and believes the organisers should have met with Prime Minister, Scott Morrison and Minister for Women Marise Payne. “Why not take advantage of having a meeting in parliament? I would have,” she says.

“Get your point across.” She likes Morrison – Dawn-Lorraine is friends with his wife, Jenny – and believes he will change the culture in Canberra. “I think he’s got the guts to do it.”

Fraser mentions Dawn-Lorraine often. “She’s been the love of my life,” she says. Fraser raised her alone after her marriage to the bookmaker and horse trainer, the late Gary Ware ended after 16 months.

They’d met in Townsville, Fraser attracted to his flamboyance and cheekiness. But in Sydney after the wedding, things went downhill.

“He started gambling, going to nightclubs, playing cards, staying there until three or four in the morning, absolutely blind drunk,” she says. Sometimes when he got home, he’d be violent towards Fraser.

His arrival home made her anxious. Like walking on eggshells? Fraser shakes her head. “Walking on fire.”

She kept quiet about the violence – something many women did in the 1960s, and still do. Fraser lost a lot of weight. She couldn’t tell her family because her brothers “would have bashed him, and I didn’t want that to happen”.

Fraser stayed mute, too, when McPherson asked if Ware hurt her. “I didn’t tell him. I knew what could have happened. I wasn’t silly.”

McPherson, whom she still calls Mr McPherson, had come around to her Balmain home to check that Fraser was okay after he threw Ware out of his premises. Ware owed him £75,000.

“I just thought, ‘Well, this is something I just have to learn to control and work it out myself’,” Fraser says. “But it got worse and worse and worse.”

Then came the night in May 1966 when Fraser could bear no more. Ware turned up very drunk, falling down the stairs. He went to Dawn-Lorraine’s room to nurse her. Fraser told him to let the baby sleep. He went to pick her up.

“That’s when all the rage came out,” Fraser says. “I picked up the (glass baby) bottle and I smashed it and I said, ‘Now, leave her alone’. I said, ‘You’ve got me to this stage now, Gary. You have to go. I don’t want to go to jail for murder, and that’s what I’ll do’.”

The rain is still falling as Fraser looks towards the river. “I loved him so much, just … anyway. Broke my heart.”

In the space of two years, she’d gone from having the celebrity wedding of a national hero to being a single mum with little income.

She couldn’t swim competitively due to a 10-year ban slapped on her after Tokyo.

The ban – which was lifted in 1968 after a legal battle but too late to compete at the Mexico games – was not for the flag-stealing episode, but for marching in the opening ceremony, against instructions not to because she had a heat within 48 hours, and for wearing an unofficial swimsuit.

It was petty and unjust, Fraser says, and it still burns.

By mid-1969, she was severely depressed. A relationship with Graeme Langlands, the captain of the Australian rugby league team, failed, and when the 100m freestylers in Mexico hit the wall, the winning time was 60 seconds.

She could have beaten that, she maintains. Fraser did 60.2 seconds in the pool in Mexico (where she went as a guest) without Olympic-level training. (Fraser won in Tokyo in 59.5 seconds.)

The weight of the things she’d lost hit hard, and she hit the booze. “I could have become an alcoholic,” Fraser says. “Because when I was drinking, I found there wasn’t a worry in the world.” She gives a weak smile. “Next morning was different.”

Back then, depression was a sign of weakness. “No one talked about it.” Suicidal thoughts started to take up space in her head. “You’ve always got it in your mind, ‘I could end this’. Fortunately, my mind was strong enough to say, ‘No, I don’t want to; I want to enjoy my life. Get out of this stupid place you’re in’.”

Her salvation was a few close friends in whom she confided, and Dawn-Lorraine.

Fraser is heartened that, today, there is greater understanding of depression and domestic violence. “It’s good that people are talking about it; it’s out now,” she says. “It’s good because you don’t have to feel guilty about it anymore. I didn’t know how to get out of it.”

She shimmies across the bench seat to get out of the rain. “I just wanted to be happy, like an ordinary family,” Fraser says. “And it didn’t happen. And I should have been happy.”

KNOCKED DOWN, UP AGAIN

The rain is so constant even the pigeons have taken up residence under the picnic shelter. We make a dash for the Noosa Boathouse restaurant. Fraser moves swiftly for her 83 years, despite her body enduring some punishing injuries.

She slipped on a wet floor when working at the pub in 1983, and fell 3m into the cellar, cracking more vertebrae in her neck and pinching her spinal cord. That aggravated Fraser’s car accident injuries and required an operation and long recovery.

She’s had a right knee replacement and two years ago, she broke her left elbow and right wrist after tripping on a raised steel barrier at a tram stop in Melbourne. It doesn’t straighten properly and limits her swimming.

Fraser mulls over the Boathouse menu and decides on a child’s fish and chips meal. “I’m not a big eater,” she says. Don’t expect to see a photo of it on Instagram. “I photograph my grandson and my daughter and my dogs. Not food,” she says, disdainfully.

The careful curation of photographs on social media that suggests perfection don’t fool her. “I don’t think anyone can have a perfect life,” Fraser says.

She’s glad social media wasn’t around when she was the wilful swimmer, getting up to hijinks and battling officialdom.

Still, she received insulting letters. “You don’t realise how many nasty people there are around the world,” Fraser says. “Is it jealousy because they haven’t achieved what you achieved? That’s what I put it down to.”

One of the most enduring whispers was about Fraser’s sexuality, starting when she was competing and had no same-sex relationships.

Her first lesbian relationship was in the early 1970s, when she met Joy Cavill, a scriptwriter who’d worked on the TV classic Skippy, and produced a film about Fraser’s swimming career.

A couple of years later, she had another relationship with a golf friend’s daughter, and they opened the Dawn Fraser Cheese Shop at Balmain together.

“You’re working with somebody,” Fraser says, “and you’re very close by and the next minute they’re touching you and you think, ‘Oh, that feels good; I’m feeling wanted’.”

She’s contemplated if her marriage trauma had made her more receptive to female companionship. “But I don’t want to put it down to that,” Fraser says. “I’m big enough and intelligent enough to know what I’m doing.”

Now, she says, she knows she’s not gay. “It wasn’t for me.”

Relationships are difficult, Fraser says, and she’s sworn off them.

“Yeah, I’m done. I think learning their way of life – there are things you don’t like in people. And it’s very hard when you’re in a relationship and you don’t like some of the things they do; it’s very hard to tell them. Especially if they don’t want to listen and they don’t want to change.”

And if you don’t want to change? Fraser grins. “That, too.”

She’s all for gay marriage, though, and voted “yes” in the plebiscite.

“I know some very lovely people who are married and that’s great,” Fraser says.

We range over other social issues. Euthanasia? “Yes – don’t let people suffer.” Youth crime? “Bring the age down to 10 and make them do a bit of time in jail.”

Political correctness? “I think it’s a good thing … let’s try to be kind to one another.” She’s very anti recreational drugs, although admits alcohol can do a lot of damage.

Fraser pauses to watch jet skiers doing laps on the river. “The rain would be hitting their face so hard it would be like needles,” she says.

It’s been pouring for days, flooding parts of the Gold Coast and northern NSW. What’s her view on climate change?

“I don’t believe in it,” she says. “I’ve grown up in this country, I’ve lived out on farms, I’ve seen droughts, I’ve seen floods – it’s not just happening. It’s been happening for centuries.”

It’s a response reminiscent of right-wing politician Pauline Hanson, whom Fraser admires. She supported Hanson’s objection to Islamic migration. “Bringing that into our country – that worries me,” she says.

Raised in a staunch Labor family, Fraser’s allegiance was broken after she ran as an independent, and won, the formerly blue-ribbon Labor seat of Balmain in 1988. The campaign by Labor was nasty, she says.

Her politics are fluid now. She’s a fan of Labor Premier Annastacia Palaszczuk, particularly for the way she has dealt with COVID-19, and loves federal political maverick Bob Katter.

Like Katter – and despite her thoughts on political correctness – she thinks it’s “disgusting” that the names of Coon cheese and Allen’s lollies Red Skins and Chicos have been changed.

“I don’t think we should ever, ever allow people to call our Aboriginals c..ns, but I don’t agree with (changing the brand name).”

Pulling down statues of historical figures with controversial pasts or views is also not on. “That’s the history of our country,” Fraser says.

Just erect more, she says. “We’ve had some beautiful Aboriginal leaders. Look at our famous painter, (Albert) Namatjira. I had the pleasure of sitting with him when he painted the ghost gums in Alice Springs.”

Fraser hopes to return next year for the Alice Springs Masters Games, of which she’s been a patron since 1985. She visits the Hermannsburg community, where Namatjira was born.

It’s past time to close the health, education and economic gap between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Australians, she says. “We’re in the 21st century and we haven’t closed it, have we? It needs to be done but who’s brave enough to do it?”

Fraser is interested in the recently announced Victorian truth-telling inquiry into the historic and ongoing wrongs towards Aboriginal people, and sees some benefit in a nationwide inquiry.

“It would turn up a lot of stones,” she says. Some of the treatment of First Nations people has been “bloody awful”.

Eventually, Fraser would like to see Australia become a republic. “We’ve got a lot of good people in this country and I think we should take a step up and say, ‘Right, we’re a republic’.”

But only once the Queen has died. “Do we want Charles and Camilla? No,” she says. “I don’t approve of what Charles did to Diana; that was cruel.”

She’s not keen on Meghan Markle, the Duchess of Sussex, either. “She knew what she was getting into; she should have accepted it, and I would say she’s swayed (Prince Harry’s) mind to get out.”

And she’s not convinced Prince Andrew is guilty of having sex with minors. “Is it just a suggestion or is it true?” She’s met the prince, and likes him.

The list of notable people in Fraser’s life is long. She’s had lunch with the Queen on the Royal Yacht Britannia, and tea with Prince Albert II of Monaco. She’s good friends with former star Romanian gymnast Nadia Comaneci, and the tennis great Martina Navratilova.

The actor Morgan Freeman is “the most beautiful man” – a friendship forged when he nursed her grandson Jackson as a baby after a feed and came off second best. “It went all over his beautiful jacket,” she grimaces.

John Singleton, the ad man and radio station owner who organised speaking events and sponsorship in the 1980s for Fraser after the pub business turned sour, remains a close friend.

And she’ll be forever indebted to the late Kerry Packer, who famously returned that Olympic flag to the Fraser clan after she put it up for a fundraising auction held in her honour. Daughter Dawn-Lorraine was heartbroken, crying before and after it went under the hammer for $52,000 to a mystery bidder.

The bidder turned out to be Packer, who walked over to Dawn-Lorraine, threw the flag on the table and said, “Now stop your bloody crying”.

The flag is now guarded jealously by Dawn-Lorraine. “I have to ask her permission to have it now,” Fraser says. “She always says, ‘Bring it straight back, Mum’.”

LOOKING FORWARD, LOOKING BACK

Like many in their later years, Fraser finds herself reminiscing about her childhood: The way she’d help her Mum boil the copper for a bath, the times she’d stoke the fire as her Dad drank whisky and told stories of Scotland.

“I think about those days quite a bit now. Because I miss Mum and Dad,” Fraser says. “I didn’t have as much time with them as the other kids did.”

She was the youngest of eight, and only brother Alick remains. Fraser is not keen on the trajectory.

“I fear death. I don’t like the word ‘death’. I try not to think about it,” she says.

“I don’t want to die in hospital. I want to die at home. But I don’t think about it very often, since my grandson came along.”

She’s promised Jackson – “a lovely gentleman” – that she will dance with him at his 21st. “That’s a promise I’ve got to keep.”

So Fraser keeps active, riding her bike and jet ski, swimming, gardening and walking. She does exercises for her brain, too, playing word games on her iPad. “I don’t want dementia.”

The pandemic has been a difficult time, because all three in the Fraser household suffer asthma. She rarely went out at the peak of the crisis. The most recent lockdown made her anxious. “I just want to be sure that I’m safe, and they’re safe,” she says.

Vaccination? Fraser’s booked in. “I don’t understand why people are against it.”

Once a COVID-normal takes hold, she can get back to work. “I love working,” says Fraser, who still does public speaking and promotional work. She mentors Olympic and Paralympic hopefuls, too, “on mental strength, how to be strong and make sure they know where they want to go”.

Pre-pandemic, Fraser had planned to go to the Tokyo Games, but now she’ll be watching them from her couch.

The Olympics are so much more than a sporting competition, she says, and she’s ultra-supportive of the all-but-done bid to get them here for 2032.

“Queensland is going to be the best region in the world to hold the Olympic Games,” she says. “I hope I’m still around.”

Because she has an idea. The woman who got into strife for marching in the opening ceremony at Tokyo 1964, whose skylarking theft of a flag is almost as famous as her impressive record of eight Olympic medals and 41 world records, knows the role she’d like to play in 2032.

It’s a little symbolic, a little cheeky and a whole lot of Dawn Fraser. Picture it: the then 94-year-old champion proudly presenting the Australian flag to her country’s flag bearer for the opening ceremony.

DV Connect Womensline 1800 811 811

Lifeline 131 114

More Coverage

Originally published as Dawn Fraser: From Olympic hero to personal tragedy