Crime Week — The true story of child killer Kathleen Folbigg

PART FOUR: KATHLEEN Folbigg was convicted of killing her four infant children. This is an exclusive chapter from the book When the Bough Breaks.

NSW

Don't miss out on the headlines from NSW. Followed categories will be added to My News.

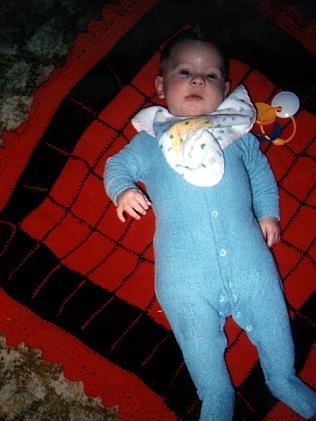

KATHLEEN Folbigg was convicted of killing her three infant children and the manslaughter of a fourth child between 1991 and 1999.

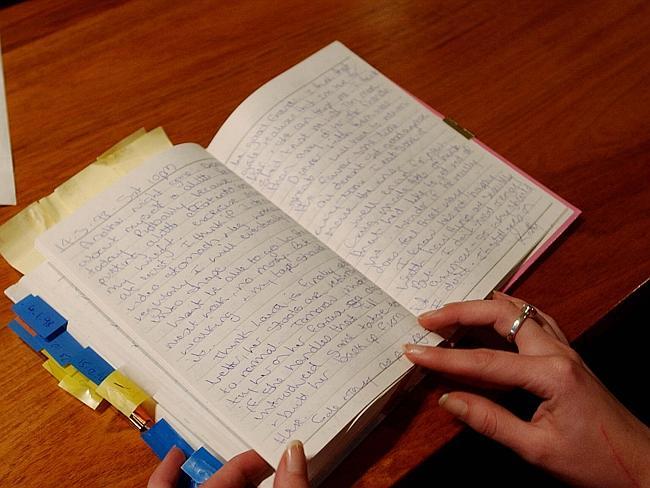

The murders were only discovered when her husband found her diary that described the deaths. Folbigg was sentenced to 40 years in jail, later reduced to 30 years.

She still maintains her innocence and has a powerful ally in 2GB’s Alan Jones, including, writing a series of letters to the radio host.

This is the fourth instalment of The Daily Telegraph’s Crime Week. This is an exclusive extract from our own reporter Matthew Benn’s book — When The Bough Breaks: The True Story of Child Killer Kathleen Folbigg

FOR A while it was like dating again. Kathy (Folbigg) would go up to the house or Craig would call on her at the flat and they would spend the evening together talking and having dinner. They reminisced, remembering the good times when they had first met, before they had children.

Craig was still so besotted by his wife that he succeeded for a while in suppressing the doubts he had about her in relation to the children. Certain phrases from her diary entries would pop into his mind when he was least expecting it, particularly the phrase ‘Obviously I am my father’s daughter’ she had used when describing the way she had lost her temper when frustrated with her children.

|

The fact that she had compared herself to her father had horrifying implications that he preferred not to contemplate. Instead he chose to focus on rebuilding his marriage with the woman he had loved for almost 15 years.

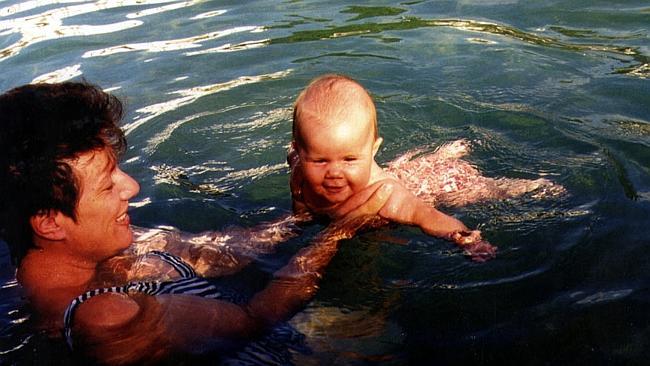

Craig was well aware of the dark history of Kathy’s biological parents and of her early childhood. Kathy had been fostered as a three-year-old by Neville and Deirdre Marlborough. At the time, her foster sister, Lea, was 15 and thrilled to have a baby sister.

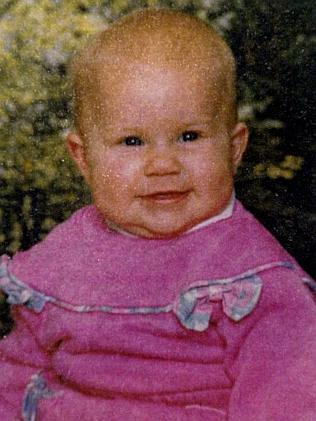

When speaking of her sister Lea said in 2003: ‘She was an adorable child; we all loved her to bits.’ Deirdre Marlborough recalled her foster daughter as a ‘very pretty little girl with really blonde curly hair’ and said that growing up Kathy had been a ‘most attractive’ child who turned into ‘a normal teenager’.

Kathy fulfilled her foster parents need for another child. Their own two children had grown up but Deirdre and Neville Marlborough loved children and yearned for more.

‘We used to take [in] children from church homes; both of us loved kids, and we just wanted another,’ said Mrs Marlborough.

CRIME WEEK — PART ONE: THE BLACK KNIGHT

CRIME WEEK — PART TWO: BRIGHT YOUNG THINGS

CRIME WEEK — PART THREE: LESBIAN VAMPIRE KILLER

CRIME WEEK — PART FOUR: THE CHILD KILLER

CRIME WEEK — PART FIVE: THE HANGING OF RONALD RYAN

‘We couldn’t adopt any of the church kids and Kathy came to us through the government.’ Her foster family loved Kathy and included her in everything they did, including several overseas holidays to Malaysia, the United States and Canada, in addition to family holidays around Australia.

Kathy had always been curious about her natural family. She would later tell Detective Bernie Ryan that her questions to the Marlboroughs about her bio- logical parents resulted in ‘brick walls in my face’ as her foster family did not want her asking too many difficult questions about her past. As a teenager Kathy finally managed to track down and meet her natural mother’s brother who told her that her father had killed her mother. However, he did not go into much more detail. This simply aroused more curiosity in Kathy about her parents and after she had met Craig and settled down with her new husband he encour- aged her to find out more. She tracked down two half-sisters in Queensland and two aunts, one in Queensland and one in Windsor, in the outer suburbs of Sydney. She made contact with them by letter and by phone. Over the years she began to meet her family members and the detail of what happened to her parents began to be filled in. The search for the truth went on over many years.

|

It was on her 32nd birthday in 1999 that Kathy and Craig went to meet her family in Windsor while some of the Queensland relatives were visiting and the full, complete and painful truth of what had happened was finally revealed to her. She met an uncle there who had looked after her for a while before she was placed in an orphanage and eventually fostered to the Marlbor- oughs. Her uncle told her that her natural family had hidden her from her father ‘because he turned out to be not a very nice sort of a man’. In fact, with her mother dead and her father in jail for her murder there was no one who wanted little Kathleen. It was painful for the family to meet her now, at her insistence, and revisit the painful past. And it was painful for one very

good reason. Kathy’s father, Thomas John Britton, was a very bad man.

Britton had been born in Wales, one of 10 children, and went to sea young. Even at that age he had a rep- utation for being quick with his fists and good with the ladies. He liked a drink as well. Britton jumped ship in Australia in the post-war years and started work on road-making crews before becoming a hoist driver at Sydney’s Balmain docks. One anonymous former friend told a Sydney newspaper years later that he was a knockabout guy with a vicious streak, particularly with women.

He said Britton had lost his job at a cement plant because he grabbed his leading hand by the throat. Apparently in another job he hit a blacksmith in the face with a 7lb (3.1kg) hammer. Britton was certainly tough and supplemented his income as a hitman and debt collector for notorious underworld figures Robert Trimbole and Lenny McPherson. When people could not pay, Thomas ‘Jack’ Britton really earnt his money — he would rough up people — break their legs or kneecap them.

When he had first arrived in Sydney Britton had married nurse Margaret Cope. They lived in Railway Avenue, East Portland, in western Sydney, and had a son — Kathleen Folbigg’s half-brother. That period of stability did not last long. In 1952 he slashed Margaret Cope’s throat with a knife. She survived and Britton served eight months in jail for inflicting grievous bodily harm. He fathered several other children before falling for the charms of Kathy’s mother, Kathleen Donavan. Whatever his skill as a ladies’ man, the effect lasted less than three years on Kathleen Donavan. In November 1968 the 39-year- old factory worker walked out on him and their baby daughter, Kathy. A gambler and drinker, it was par for the course for her — she had abandoned a previous husband with their daughter and adopted son.

Forty-five-year-old Britton suspected Kathleen Donavan was cheating on him. In the police statement he later gave, Britton said she had left him with the baby during a family picnic at Nielsen Park, Vaucluse, on 24 November 1968. ‘I objected to her drinking so much with the child present. She told me she would drink what she liked, when she liked and with whom she liked,’ Britton said.

‘She then drank one beer quick and went to drink another one. I took it from her and put it on the table. She just grabbed her bag and went. She left the child with me. She had my week’s wages in her bag, about $70.’

Broke, Britton took baby Kathy back on the ferry across the harbour to Drummoyne Wharf and then carried her and their two bags of picnic things to their home in Darvall Street, Balmain.

Meanwhile, after storming off, Kathleen had gone to stay with her friends Vince and Moya O’Brien in Pritchard Street, Annandale. Moya O’Brien knew her friend Kathleen was in trouble. Kathleen had told her that every morning Britton would hold a knife to her throat and ask: ‘Will I or won’t I?’ Thirty-five years later Moya O’Brien recalled: ‘She came knocking on our door, but she was definitely not drunk; she was in a tizz. Her intention was to get that little child back. She should have run and run and run, but I know she didn’t want to leave that baby. She was sincere. She opened a bank account; she made one deposit before she died. That baby was mother’s little girl. Her mum used to carry her around everywhere on her hip. I think everyone should know that she was a good mother ... Her father was the monster.’

Back in Balmain, baby Kathy was fretting for her mother. Britton tracked Kathleen Donavan down to the house in Annandale and knocked on the door.

‘I begged and pleaded with her to come back to me and the child. She refused point-blank. She said she didn’t want anything to do with me or the baby,’ he later said. ‘It was from then that it all started to boil up inside me. I gave her a smack in the mouth.’

|

Britton needed money so he took baby Kathy to be cared for in the Glebe home of his friend Charles Budden and his wife while he went back to work on the docks. Kathleen Donavan was constantly on his mind. A few days later he was travelling on the bus when he saw her in a Balmain street. He jumped off and again begged her to come home. When that did not work he threatened to report her to the social services. He later said she told him ‘she could not care less and was not coming home’. They started arguing about her blowing his $70 at the bookies and Kathleen retreated into a butcher’s shop.

Britton followed her inside and punched her in the face.

Britton considered himself a reasonably good drinker and on the night of 8 December 1968 sank 14 to 16 middies of beer before finding himself again outside the Pritchard Street home in Annandale where Kathleen Donavan was staying. When she arrived home in a taxi, Britton approached her. He later gave an account of their conversation. ‘I could see she had been drinking. I then asked her again would she consider coming back home. I told her the baby was fretting for her and not eating. She said she couldn’t care less and she was not coming home.’

Neighbours heard them arguing. Moya O’Brien later reported she heard him tell Kathleen: ‘You are a black slut for leaving an 18-month-old baby. I’ll stick a knife in your ribs.’

Britton stabbed Kathleen 24 times with a 25cm- long carving knife. She died in the street.

Later he spoke of his crime: ‘I done what I done. Then I threw the knife on to the footpath. I couldn’t realise that she was dead. I kissed her and cradled her in my arms. I then told two people to ring the police as I thought I had done my wife some harm. I just waited there until the police arrived. When she was on the ground I rearranged her clothes as I did not want anyone to see her like that. The bloke upstairs told me to get away from her and I told him to get to buggery.’

Neighbour Elizabeth Lorik said at the time that she heard the couple fighting she went out to her front garden to investigate. ‘I saw a man with a knife in his right hand. I saw him push the knife into her left breast. He dropped the knife, and then he bent down and pulled her dress down because it had been caught up. The man looked up and asked me: “Will somebody ring the police?” ‘I said: “We already did”.

‘He said: “I had to kill her because she’d kill my child.” ’

She then saw Britton kneel beside the woman, kiss her and say ‘I’m sorry I had to do it’.

Britton was tried and found guilty of murdering his de facto wife Kathleen Donavan. On 26 May 1969 Mr Justice Le Gay Brereton sentenced him to life imprison- ment. He served 14 years in prison and was then deported. Britton returned to Pontypool, his home village in Wales — still home to many of his siblings and their families — where he lied about his time in Australia.

Britton’s first child, a son now in his 50s, had very little to do with him when he returned but a nephew, Roger Brandon, and Roger’s wife, Margaret, did have contact with him. He never told them about his daughter Kathleen.

In fact, Kathleen Folbigg did not know of her father’s whereabouts until his family was tracked down by The Australian newspaper when her own trial hit national and international headlines. By then Jack Britton was already dead. Mr Brandon told the newspaper: ‘Jack never really opened up about his time in Australia so we never really knew what happened to him out there.’

He knew his uncle had served a jail term in Aus- tralia but the details of the reason for this remained hazy. ‘He said he had killed an Italian man in self- defence and it had something to do with Australian crime gangs,’ said Mr Britton.

The locals at Britton’s regular drinking haunt, the White Hart, knew to steer well clear of him. Even in old age he had been known to successfully take on bigger men 50 years his junior. ‘He was not a big guy but he was a tough old fellow with a real fiery temper,’ said Mr Brandon.

Peter Bevan, White Hart publican, knew Britton well. ‘He was in here every afternoon and every night. Jack could be happy enough but he could also be bloody cantankerous. We all knew he did time in Australia but he told me he had caught a bloke in bed with his wife and killed him on the spot.’

Another drinker claimed: ‘He told me it was some guy who had been on with his wife but he said he killed him in a pub.’

Britton celebrated his 75th birthday in October 1998 and then his health deteriorated. On the evening of 23 February 1999 Mr Brandon called in to check on Britton at his flat and found him dead in the chair at the kitchen table, with his evening meal half ready. Brandon’s wife, Margaret, had been the last person to see him alive when she popped in to see him that morning.

Mr Brandon set about going through Britton’s personal effects. In one box he found a well-worn envelope containing a lock of hair — the fine curly golden-red hair of a young child. ‘Jack did mumble something once about having the hair of a daughter or granddaughter but it never made any sense because we didn’t know about any daughter,’ said Mr Brandon later.

Kathleen Folbigg’s no-good father had kept a lock of her baby hair until the day he died, six days before his baby granddaughter, Laura Folbigg, would die on the other side of the world.

Kathy had only been 18 months old when her father had murdered her mother with a carving knife and could remember nothing about the killing or her parents. After reading her own Department of Community Services files and finding out stories from her natural family about her mother and father, she felt her father had wasted his life, and her mother had not been much better — Kathy realised she had been a drunk and a gambler and had often left her baby daughter in the care of others.

CRIME WEEK — PART ONE: THE BLACK KNIGHT

CRIME WEEK — PART TWO: BRIGHT YOUNG THINGS

CRIME WEEK — PART THREE: LESBIAN VAMPIRE KILLER

CRIME WEEK — PART FOUR: THE CHILD KILLER

CRIME WEEK — PART FIVE: THE HANGING OF RONALD RYAN

Craig knew that when Kathy had written in her diary on 14 October 1996 the words ‘Obviously I am my father’s daughter’ she had already known a great deal about the man who had killed her mother. After Craig had read her diary, she told him that the diary entry simply meant that in her eyes her father was a loser and she was a loser as well. In the weeks following their reconciliation in May 1999, despite already having taken his suspicions about Kathy to the police, Craig wanted so much to believe that his wife was telling him the truth that he ignored any doubts that crept into his mind. He tried to make a new life for himself and the woman that he continued to love, the mother of his four dead children — a woman with a tragic past.

He was in here every afternoon and every night. Jack could be happy enough but he could also be bloody cantankerous. We all knew he did time in Australia but he told me he had caught a bloke in bed with his wife and killed him on the spot

He was in here every afternoon and every night. Jack could be happy enough but he could also be bloody cantankerous. We all knew he did time in Australia but he told me he had caught a bloke in bed with his wife and killed him on the spot