Mark Donaldson, VC: I survived an IED attack, then my chopper crashed

Mark Donaldson VC describes the day in Afghanistan a roadside IED threw him 7m into the air. Soon afterwards, he was running for his life when his rescue helicopter crashed. This is the day an Australian war hero almost died twice.

Following the phenomenal success of the groundbreaking documentary series Voodoo Medics, The Daily Telegraph is bringing you War Stories — powerful stories of courage and heroism — with exclusive book extracts from the frontline. This is the story of how Mark Donaldson, VC, dodged certain death twice in a single battle. This is his War Story.

Our squadron was on the eastern side of Uruzgan, near Kakarak, searching for an IED maker who was running free.

We planned to take a Bushmaster to an overwatch spot, make them think we were staying there for the night, and then drive into the green belt and drop off the patrols who would set up the ambushes, hoping to catch the IED maker in the process of planting his handiwork.

The targeted area was a known Taliban compound, what we called an enduring target, meaning they weren’t necessarily there at any given moment. This is opposed to a time-sensitive target, which is when the person is in a place for a short time, and a dynamic target, which is a suspect who is moving around.

READ MORE:

The private pain of Mark Donaldson

The secret world of elite combat medics

If the IED maker wasn’t at this enduring target, we would still blow it up a bit, to make him feel insecure, knowing that we knew about it. It kept the pressure on the enemy and denied them freedom of action, which allowed us more opportunities to get them. As well, it allowed other military units and agencies to conduct their work in relative safety.

Our ambush-setting patrols were dropped off in different places. I was in the front Bushmaster, on the back rear right gunner’s hole. An engineer in the turret, with a gun, guided two other bomb-detection guys sweeping out the front.

Just before midnight, we came over a little rise. We were following a line to the side of the road, where the engineers deemed it safer. Another road came in from the side and there was a vulnerable point at a dry aqueduct.

There was a pile of rocks with a stick at the top of the hill overlooking it, suggesting enemy presence. It was suggested we clear a lane and drive around the aqueduct.

For some reason, I decided I wanted to be at the front of the truck. I walked across the top of the Bushmaster, where we had our swags piled up. I sat on the swags behind the engineer, Dinger, in the front turret.

The engineers out the front signalled us to stop and began digging away. They deemed it okay and moved on. There was a little rock wall on the side of the secondary road. We crept forward, crept forward, and the next moment … BOOM!

I remember a loud crack and then a ringing in my ears. I felt weightless, out of control. I couldn’t see anything — it was pitch-black.

In my head I thought, Shit, we’ve hit an IED. I was tumbling and spinning in the air. I wasn’t so shocked that I didn’t know where I was: I was totally under the control of the blast’s momentum.

I felt myself reach the apex of my flight. My stomach just floated as I stalled in the air. Then — I’m coming down. Holy f**k, I must be a long way up — I still haven’t hit the earth.

READ MORE:

Inside the ‘movie scene’ firefight

‘There was a lot of blood and that metallic smell’

Then — Bang. My face, wrists and knees hit metal. I bounced and did another somersault before hitting the dirt face-first. My rifle was still in my hand. Everything was black.

All I could hear was a hissing, wheezing, grating sound. I must have bounced on the Bushmaster’s bonnet. I went to roll to the side, thinking the vehicle was still moving and might run over me. My legs went out from under me and I rolled into an aqueduct.

I stumbled around, and then lay in the dry watercourse, waiting to get shot at. I heard voices on the radio in the Bushmaster. I grabbed my dick to make sure it was there, grabbed my legs and arms, did a full check.

I was more numb than sore, though soon my wrist began to throb. I had about 20 to 25 kilos of gear as well as my own weight. Later I figured out that I’d come down from about seven metres in the air onto the bonnet, then done a full somersault onto the ground.

The immediate danger was an ambush. When an IED has gone off, you do a five-metre scan and then a 25-metre scan to make sure there aren’t more explosives around. The Talibs often set mines or other IEDs around the first one to get more blokes as they rush in.

We were very conscious of that, so the others were going through that procedure as I lay in the creek bed. I heard my PC on the radio telling everyone to sound off, or check in.

Another of our patrol, who had also been in the vehicle, had landed in the crater left by the blast. That would have been hot as hell. He said he felt like he was on fire.

They assessed the IED to be 30—40 kilos of explosives — enough to move the big vehicle about five metres.

Our first responders from the van behind us rushed in. We were very light on for people, because we’d dropped those patrols off earlier. Our operators with the dog found an enemy fighter hiding behind a wall with a mobile phone, and detained him. A medic checked me out. My NVGs had been blown off my helmet. I said, ‘If you could find them, that’d be awesome.’

The driver lay next to us in the aqueduct, wide-eyed, saying, ‘Holy shit!’ Then he looked at his weapon and said, ‘I guess I should go to action, eh.’ That is, get his weapon ready to fire. I said, ‘Yeah, that’d be a good idea.’ Our drivers were regular army guys from the Armoured Corps who usually drove tanks, but we were using them as our Bushmaster drivers. They did a good job.

I was bleeding a bit from my knees and my wrist was sore. My mate who’d also been thrown out of the Bushmaster had injured his back, and was put on a stretcher with a cannula in his arm, but he was lucky not to have ball-bearing holes through him. There were plenty of those holes in the Bushmaster.

I was lucky too. If I’d stayed in the hatch at the back, there was a good chance I’d have been taken out.

We had a mobility kill, as our vehicle had lost its wheels. Some of the other patrols got around us and pushed some Bushmasters around for security, and they called in an AME. My patrolmate had to be stretchered out. I said I was okay, but they insisted I go too.

We were waiting for the American Black Hawk to come in from Tarin Kowt. As the Hawk finally approached, a strobe was dropped on the dirt to mark out the landing zone. The helicopter’s descent created a brown-out, a huge cloud of dust the pilot couldn’t see through. That same day there had been dust storms around Kandahar, which meant AME Red, or no flying. The pilot pulled out and tried to come in again. Again he couldn’t get it.

For the third attempt, he came in from a different angle. I was watching through my NVGs, which the medic had found. The Black Hawk’s rotor blades looked like a huge phosphorescent disc; I could see the static electricity.

He came in really hot, about 10 metres from us, into a paddock that had been ploughed into long parallel ruts. At the last moment, I thought, Holy f**k, he’s about to crash. His wheels hit a rut and flipped the entire machine. The main rotor got flung over towards us and the blades dug into the ground, tearing up and flying everywhere. Now only about seven metres from us, the helicopter was being ripped apart. I could hear the shearing of the blades and the whipping, whirring sound of bits of rock and metal flying past us.

The dust blasted out in a blinding cloud. As the main rotor stuck, the body auto-rotated and the tail rotor spun around straight towards us. Everyone was yelling out, ‘Run!’

Some of us turned back into the dust cloud to pick up the injured guy, who, we remembered, was strapped to a stretcher on the ground. But he came barrelling past us with the stretcher still attached to him, sprinting away with the drip hanging out of his arm.

As the dust settled, I went closer to the helicopter. It was slowly shutting itself down and gave out what sounded like one big sigh before shutting down completely. The pilot was sitting in the cockpit. The Americans liked to dress up, and he had a helmet like a centurion in ancient Rome, with a brush running down the top of it. He was sitting there, just saying ‘F**k! F**k! F**k!’ and smashing his helmet on the dashboard.

They called it a ‘hard landing’, not a crash — an interesting euphemism. It looked like a crash to me. A blade was found 100 metres away. One of our guys in another Bushmaster had been sitting there next to an antenna. As the helicopter crashed, he ducked and a flying piece of blade sliced the antenna in two. Another piece of blade or rock put a massive dent in the bin at the side of a Bushmaster the same distance away.

It was only luck that got us through. I couldn’t believe it. I’d been blown up by an IED and then, forty minutes later, nearly had the rescue helicopter crash on top of me. The engineers had found a second IED in the small wall next to our blown-up Bushmaster, set up to hit any first responders to the initial incident. This would have caused a lot more damage if it had gone off.

Our technology had enabled us to block the remote signal that was sent to set it off. The whole scenario resembled the type of elaborate game they might have played on us in training: ‘You’ve been blown up, and you’re being AME’d out. Get ready for that. Now — oh, it’s changed again, your helicopter has crashed.’

If they’d put us through this in training, we would have said, ‘Don’t be ridiculous, things never change that fast.’ But that was exactly how it had happened.

Our mission was aborted, and it was now about getting out of there. Everyone went into an all-round security set-up. We had to wait till morning for a downed aircraft recovery team (DART), to come up with a Chinook from Kandahar.

Being injured, I got to fly to TK first for a check-up before they went back out and picked up the downed Hawk. The other boys had to wait out there another eighteen hours for coalition partners to come and prepare the Bushmaster so they could load it onto a truck and take it away. By then, they wouldn’t have slept for two days. It would have been hard for them to set up a decent defensive perimeter for that length of time, knowing they were exposed.

As it happened, when the recovery team came to lift the helicopter it flipped again and dropped into the dirt, causing more damage. Then the Chinook took it over the blown-up Bushmaster, and nearly clipped it, only missing by a metre. That would have brought the Chinook down too.

Unknown to me, the next morning some personnel in cams turned up at our house in Fremantle. Emma panicked. They said, ‘We’re here to let you know there’s been an incident overseas. Mark’s been out on a mission, there’s been an IED explosion, and he was all right. But then a helicopter went to get them and crashed, and we don’t know any more.’

These things are indescribably hard on your family. Emma was in a terrible state, thinking, Thanks a lot! What do I take from that?

Very soon after, I was able to ring her up and tell her I was safe. But it wouldn’t be long before she would get another visit from army personnel.

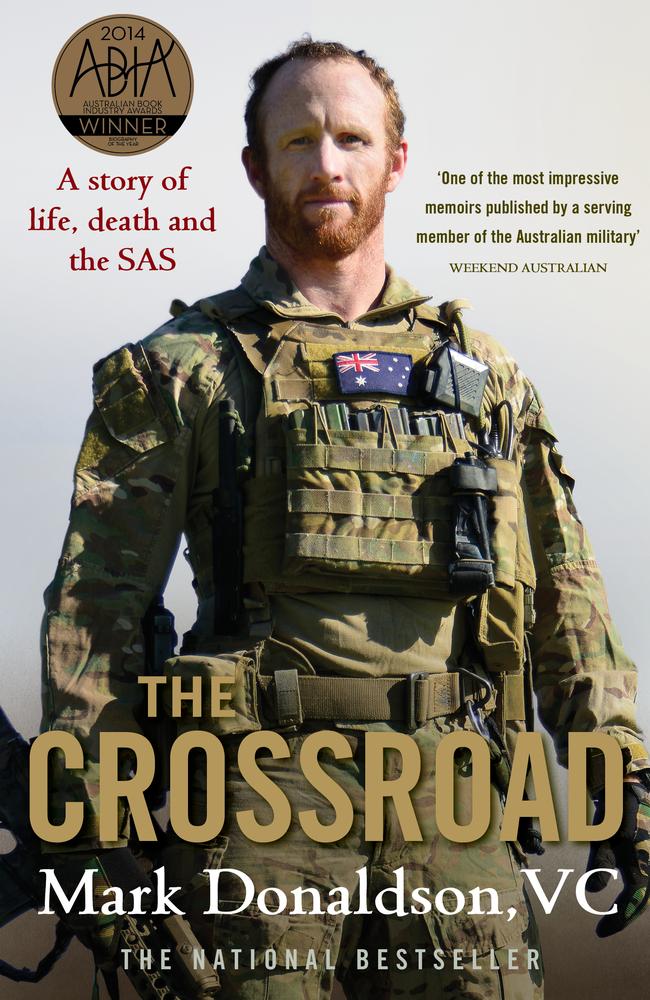

The Crossroad by Mark Donaldson, VC is published by Macmillan Australia, RRP $29.99 and is available now in all good bookstores.