Bondi Junction stabbings: Experts call for mental health system reform

Experts claim a glaring gap between hospital visits and incarceration for mentally unwell patients has existed since the 1970s, when Australia began to shut down asylums and mental health hospitals.

NSW

Don't miss out on the headlines from NSW. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Health experts claim a glaring gap between hospital visits and incarceration for mentally unwell patients has existed since the 1970s, when Australia began to shut down asylums and mental health hospitals.

Consultant psychiatrist Dr Richard Wu, who was trained at the Cumberland psychiatric hospital, said problems emerged decades ago when Sydney’s asylums started closing following the introduction of antipsychotic medications.

“There was a lot of high hopes of what these medications could do,” he said.

In Sydney, community health centres became the norm.

“But then people found that you need a lot of resources, including accommodation and employment, which was always very hard, and a lot of staff to really catch the discharged patients and help them adequately,” Dr Wu said.

“This is where people start to slip through the gaps. A lot of chronically psychotic patients were discharged from the asylums, becoming itinerant, living at hostels and not necessarily wanting to be linked up with halfway houses or group homes.

“This back-ward-to-back-alley problem was well known in the 1970s and 1980s. We’re still dealing with the same dilemma 50 years on. Ideally, you would have more shelters, better facilitated drop-in centres, and more workers but, personally, I think the old asylums also had advantages.”

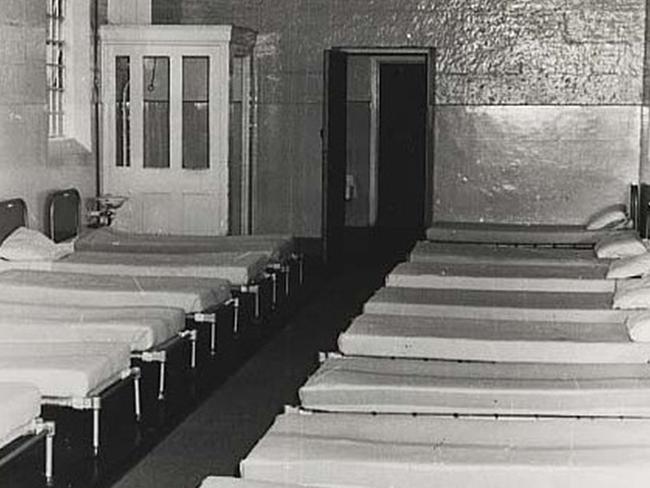

Sydney’s old psychiatric hospitals were dotted around the Parramatta River, including Cumberland, Rydalmere, Gladesville, and Rozelle.

“They were huge,” Dr Wu said. “Patients were able to run their own dairy farms, bake their own bread, and vineyards.

“You can’t say that they were less happy than patients who ended up in the back alley in the ’70s and since.”

Mental Health Minister Rose Jackson has called for more long-term accommodation options for people with acute mental health concerns to better support rough sleepers who suffer with untreated illness.

She also acknowledged that systems managing homelessness need to be better linked with medical records, so people sleeping rough can get the best care when they are told to move on.

“It’s like doing detective work sometimes as a healthcare worker,” NSW mental health nurse Shannon May told The Daily Telegraph.

When patients aren’t able to provide their name, identification, or perhaps their birthday, the process of locating health records becomes almost impossible.

“You’re digging and digging and sometimes we don’t even have enough information to even find the details of their history,” May said.

“In terms of treatment going forward, if you’re basing decisions off just what you’re seeing, a patient may have had particular antipsychotic medication or mood stabiliser in the past and it’s made them worse — and you don’t know.”

“A lot of the systems we use are so old and archaic. Nothing is streamlined, so it’s not like all the information is there. It makes it incredibly difficult to keep continuity of care. We don’t learn about things that have happened with patients after they’re discharged, unless it’s in the news.”

Jackson’s comments came after Premier Chris Minns said on Tuesday that he wanted to “urgently” investigate the state’s taxpayer-funded mental health programs in the wake of the Bondi Junction stabbing rampage.

On Wednesday, Premier Minns acknowledged “change is needed” around mental health funding following the horror knife attack in Bondi Junction where a man suffering from schizophrenia stabbed six people to death and injured 12 others.

“I understand the public wants to make sure that for those that might be suffering a mental break or have a schizophrenic diagnosis, that they’re safe in those circumstances,” Mr Minns said on Sunrise on Wednesday morning.

“We also have to make sure that the support services are in place for those that feel vulnerable.

“It’s not an easy part of the law and the policy is difficult. If it was easy, someone would have done it before today, but I fully admit that change may be needed and we’re certainly open to that.”

Murderer Joel Cauchi had been managing a schizophrenia diagnosis in Queensland but was not known as having mental health needs to authorities in NSW.

“There’s a direct link between the public community mental centres and the public hospitals, and there needs to be,” Dr Wu said.

“This is why a lot of people with more severe mental health illnesses need to be in the public sector.”

“In the private sector, the problem is if you have a person who is psychotic or delusional and they choose to be non-compliant. They don’t come in and you’ve lost them.”

However, understaffing is another core issue for the public sector, with a five-to-one ratio of severely ill patients assigned to a single nurse in May’s experience.

“When you’re dividing your time up five ways, the irony is the more you’re supposed to be looking at a patient and checking on them, the more you’re supposed to be writing about them. The documentation is part of the problem.

“It takes time away from engagement because there is so much more emphasis placed on the bureaucratic process than quality care.”

Ultimately, May said: “The Bondi tragedy is reflective of the way that our mental health system operates and its problems, more than the risks that mental illness itself poses to society,” May said.