Birth of the City Circle: How financial strife, wartime and death of its visionary delayed Sydney’s transport loop for so many years

AFTER NSW Premier Mike Baird’s announcement this week of three new Sydney CBD stations, we take a look at how the City Circle took nearly 50 years to build from conception to completion.

NSW

Don't miss out on the headlines from NSW. Followed categories will be added to My News.

THE NSW government has announced a plan to fun major infrastructure improvements across NSW through the sale of the state-owned network of electricity poles and wires. Among the projects to be funded is a second harbour rail crossing, a fast train from the city’s northwest to Bankstown and the construction of three new underground CBD stations. The proposals, which include major road upgrades like the Westconnex project, is on a scale that has not been seen in Sydney for decades. Here we take a look at the last time this scale of infrastructure upgrade took place in the city.

THE tunnels of the underground rail network have often been criticised for one reason or another — the inefficiency of trains, the noise, the dust, the overcrowding, the rats or the lack of ventilation. They have even been criticised because the tunnels would not allow an easy escape in the event of a terrorist attack.

That is not really surprising given that they were designed in an era when the word terrorism was unknown, and activities we would call terrorism today were perpetrated only by lone anarchist groups in distant Europe.

While Sydney is currently in the grip of a light rail mania and there have always been those who lament the demise of Sydney’s trams in the 1950s and early ‘60s, our underground train network was once the latest word in transport and the trams were the problem.

Sydney at the beginning of the 20th century was a congested mess, mostly because of the trams. The expanding city’s only railway line ended at Central station, which, despite its name, was hardly central to the busy main business district. The station itself had only been completed in 1906 and before that the railway lines had ended at Redfern (previously known as Sydney Terminus or Central).

This meant people coming into the city had to get off the train and find their own way to the central business district or the wharf. Usually this was aboard a tram or by cab — in those days the cabs were mainly hansom cabs, horse-drawn carriages. But increasingly cars were helping trams and carriages create traffic on city streets.

A 1908-09 royal commission into the “Improvement of the City of Sydney and its Suburbs”, headed by Lord Mayor Thomas Hughes, attempted to address some of these problems. The commission’s report famously recommended a bridge across the Harbour to link Sydney to the North Shore — but it also included a recommendation for an underground rail system for the centre of the city, to be linked to suburban lines.

The recommendation was not immediately taken up, but it did inspire John Job Crew Bradfield, who became assistant engineer for the NSW Department of Public Works in 1909, and later its chief engineer. While he is mostly associated with the Harbour Bridge project, Bradfield was concerned with many aspects of city planning.

He wrote papers on building an underground network and electrification of the Sydney train system (steam engines were unsuited to tunnels for obvious reasons).

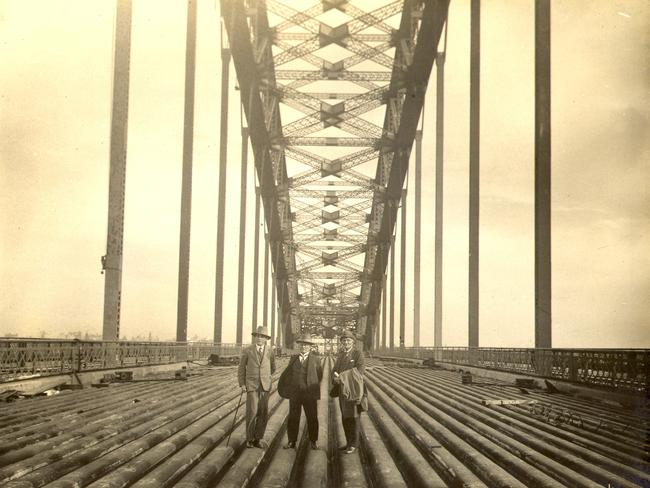

When Bradfield discussed plans for a bridge with acting premier William Holman in 1911, he linked it to improvement of the rail network, including a line over the bridge itself, served by lines under the city.

World War I broke out while Bradfield was working on his plans, forestalling any quick start. He received approval in 1915 but his initial estimates of pound stg. 18 million for the system meant that the government had to scrap some parts of his plan and delay others.

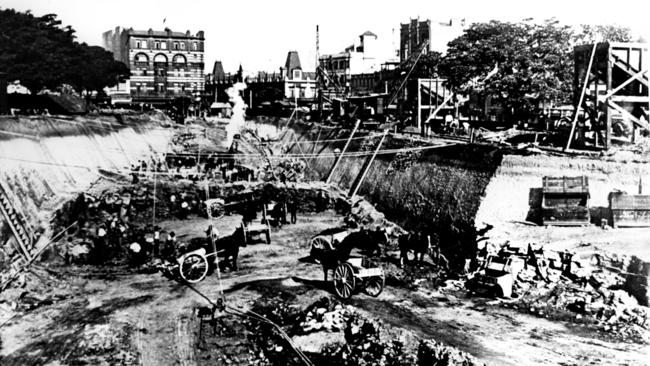

The big task of digging tunnels for the railway lines and the stations began in 1916 with the boring of the first holes in Sydney’s streets by construction firm Norton Griffiths and Co. But after it had completed some of the tunnelling as far as Macquarie St, the government cancelled the construction firm’s contract in 1917 and work was taken over by the Department of Railways to save costs.

The network hit another snag in 1918 when work was suspended due to more financial strife. But, after the war, mass-produced cars flooded NSW roads — in particular Sydney’s — creating chaos. The need for a train network was greater than ever. Work resumed in 1922.

The excavations presented Bradfield with some difficulties. Construction crews had to shore up existing buildings near or above the tunnels, including a corner of the Queen Victoria Building.

A major undertaking, it would have made modern-day conservationists and city planners wince at its scale and its threat to Sydney landmarks. A big part of Hyde Park was dug up to allow tunnels to be built for Museum and St James stations. Much of the dirt and rubble from excavations on George St and at Hyde Park was laboriously taken away by horse and cart.

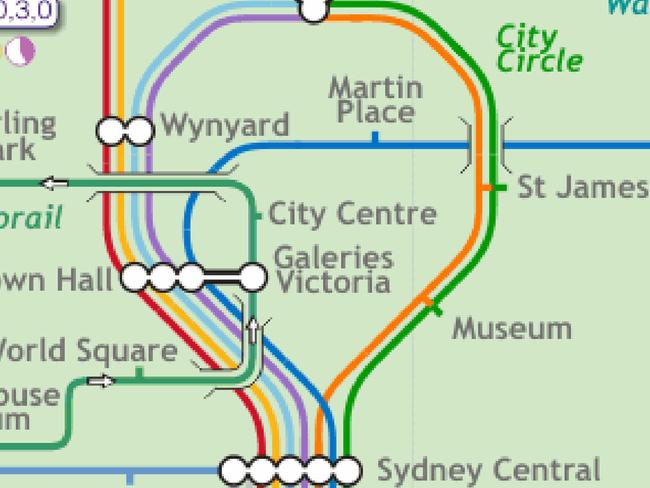

The first trains rolled over the network in 1926, just months after the state’s first electric train ran between Central and Oatley in March. The underground service was open to the public in December. But the loop envisaged by Bradfield was not complete. Wynyard and St James were both terminals where trains had to reverse direction. Tunnels were dug that would eventually connect St James and Wynyard stations via Circular Quay but it was not until 1956 that the “missing link” at the Quay would be opened. During the war the tunnels housed bomb shelters and a military headquarters.

An extra line was meant to stretch from the north-western suburbs to Town Hall, then do a sharp U-turn to reach St James station before veering left to the Eastern Suburbs via Darlinghust.

This line, of course, was never built, and left Town Hall with two superfluous low-level platforms. These were eventually used for the Eastern Suburbs Line, which was given a new route. The switch left St James with two extra platforms — with the space for the phantom tracks covered over a few years ago to create one huge platform.

At Wynyard walls were removed in the 1940s for better ventilation. Overcrowding was constant as people waited for trams (on platforms 1 and 2, now part of an underground car park) or for trains to reverse.

It was also frequently criticised as dirty. It seemed to collect dust and rats with food from the bins of nearby restaurants were often seen in the tunnels. A 1954 study also identified dangerous germs in the atmosphere. But at least Sydney had an underground; it would be decades before Melbourne followed.

Bradfield died in 1943 without seeing his loop closed and his vision of the Sydney “City Circle” line ever come to completion.