Ben Pike reveals how his father’s demons impacted on his life

SUNDAY Telegraph journalist Ben Pike tried in vain to help his tortured dad Chris defeat his demons, but in the end he took his own life. Here he details how his father’s actions impacted on his life.

NSW

Don't miss out on the headlines from NSW. Followed categories will be added to My News.

HONOUR thy father and thy mother. Despite my lack of faith, this passage from the Bible has always resonated with me.

If your parents have brought you into the world, raised you, shaped you and turned you into the person you are today, it is only fitting that you take the time to repay the debt.

But if your father has done almost everything in his power to destroy himself and everyone around him, and refuses to listen to anything other than his own delusions, then how can anyone then be expected to deliver on your side of the bargain?

This is the dilemma I faced in the eight years leading up to my father’s suicide at age 53.

I was 24 when he died on January 24, 2009. He was a man who gave me so much and loved me to the end of the earth, but would have also broken me if I hadn’t left home and ceased having a close relationship with him.

How did it get to this?

And what could I have done to prevent his death?

****

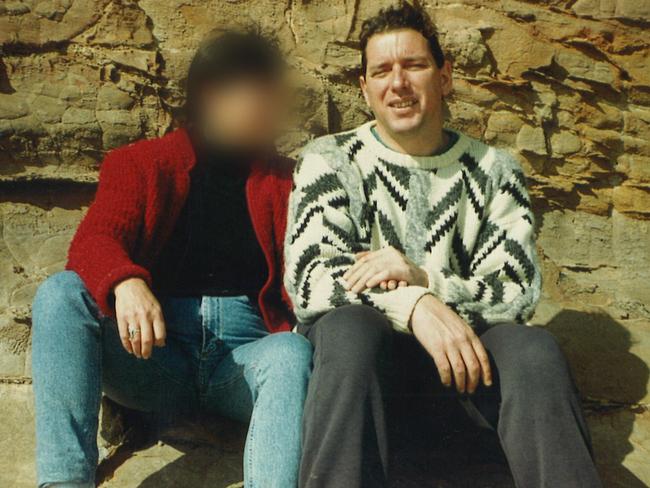

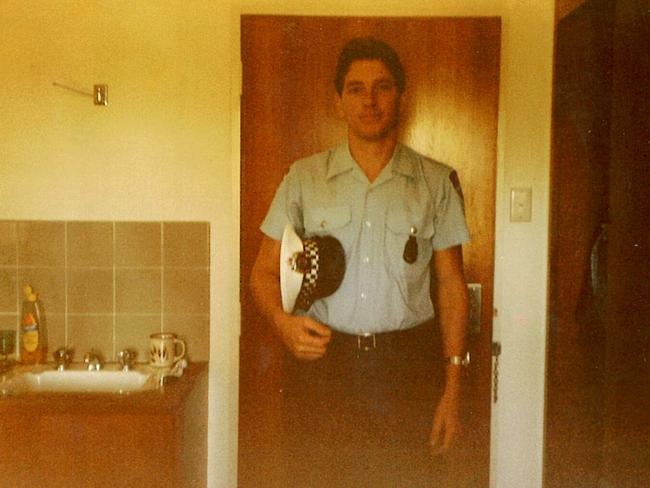

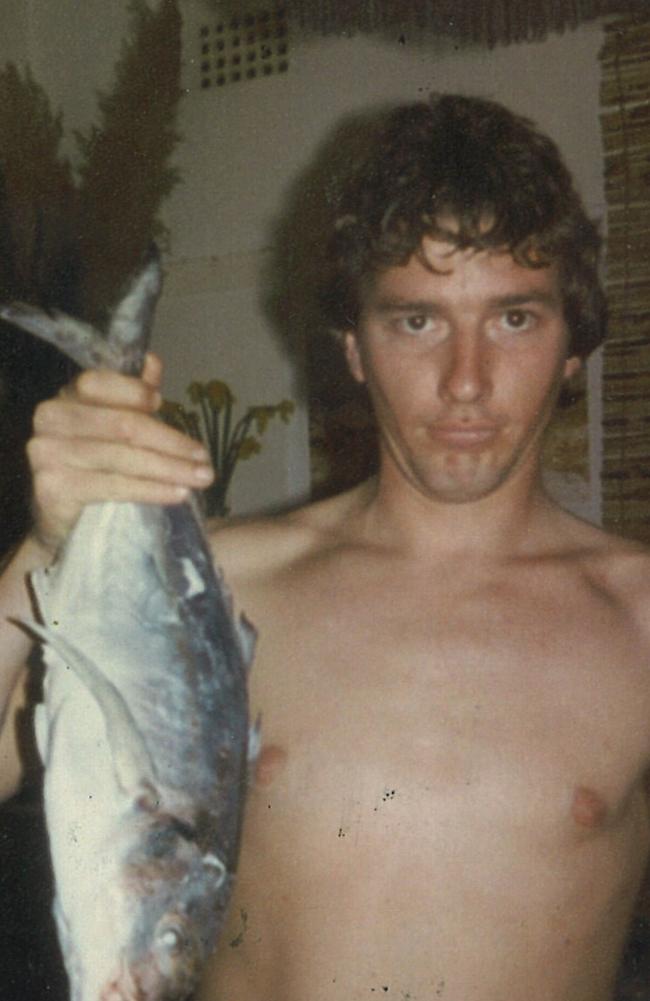

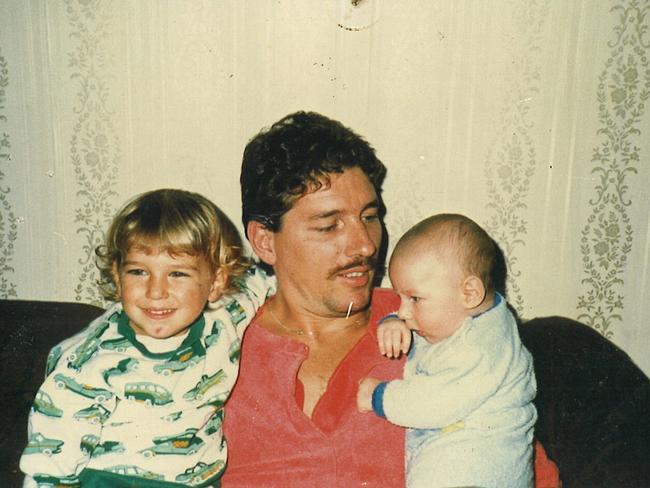

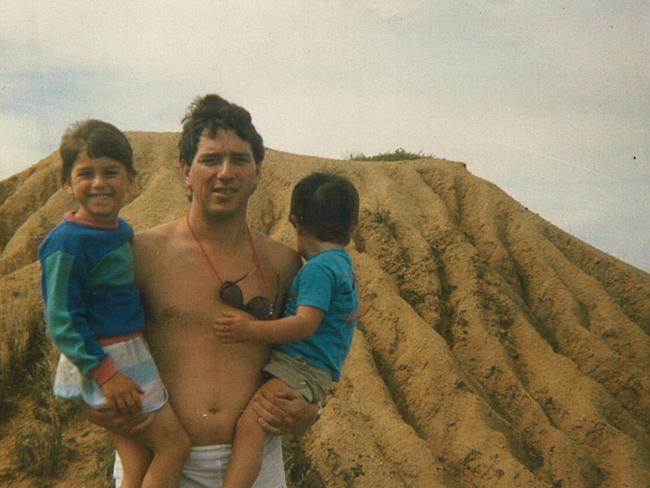

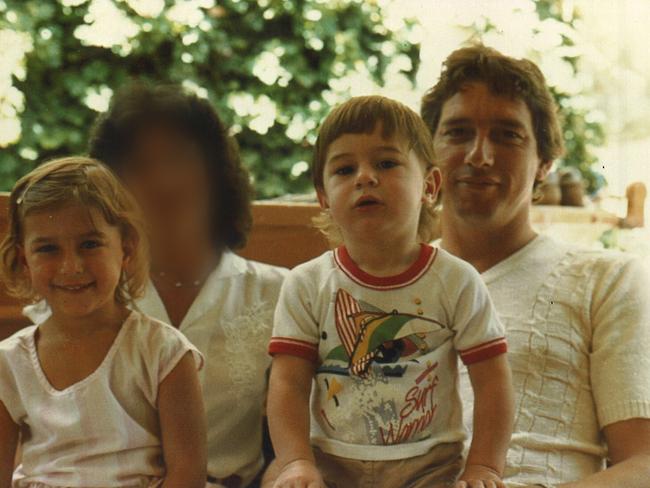

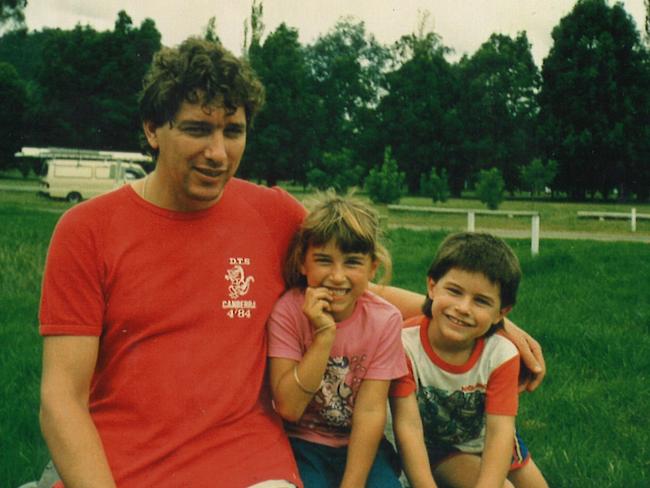

MY MATES always used to say that my old man, Chris Pike, looked like a cop. Tall, broad shouldered with a square jaw, he looked like the very stern face of the law.

Everybody knew that my father was a man to be loved, respected and feared. Having grown up in the Melbourne working class suburb of St Albans before moving to a housing commission flat in Carlton at age 12, he knew how to fight and he knew how to scare people.

This made him perfect for being a detective in the drug and fraud squads of the AFP in the 1980s and 1990s.

One of my earliest memories is of him and his gun.

He had a chest holster which he put on over his shirt in the morning, along with another one which strapped to his ankle.

He also had a waist holster which connected onto his belt. It sits on my shelf to this day.

He looked like Dirty Harry and he liked to act like him too. He kept his revolver on top of his walk-in wardrobe.

I remember sneaking into his room to look at it when he was snoring. He always told me not to go near the gun.

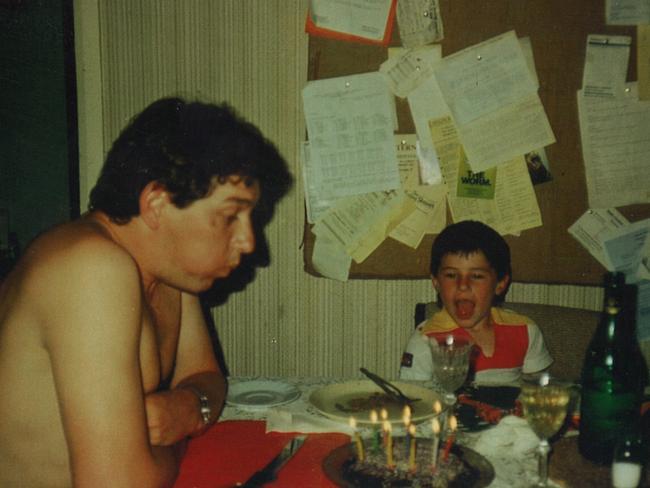

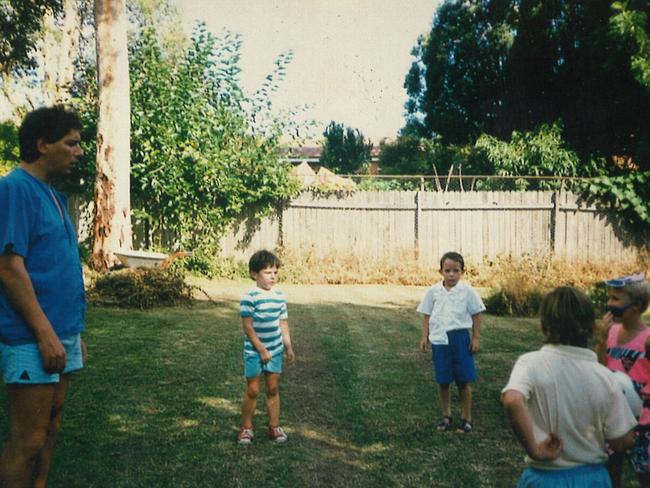

At my eighth birthday party there were plenty of fake guns, with me and my mates running around with cap guns. But the main show was yet to come.

After amazing the kids by blowing smoke rings with his Peter Jackson cigarettes, Dad brought out his revolver to show my friends

I remember the wooden handle, black steel and sheer weight of this lethal weapon in my tiny hands. It might as well have been a bazooka.

My old man’s gun may not have made the same “bang” like our plastic cap guns, but we all got to pull the trigger and watch the hammer hit the frame of the weapon.

I’ll never forget how my mate squinted as he pulled the trigger.

They talked about it for weeks.

****

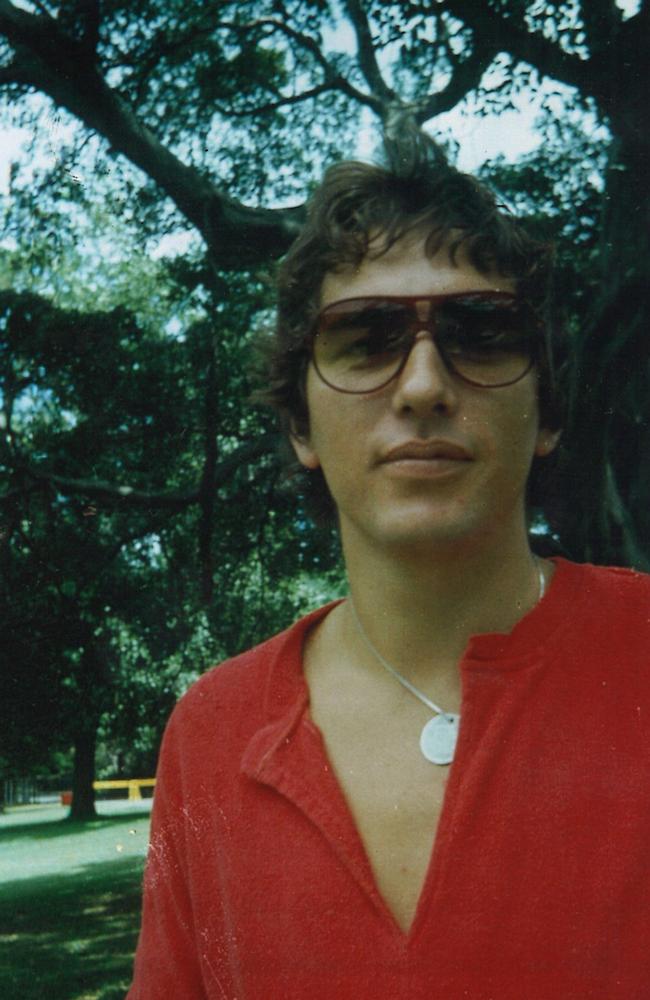

I LIKE to put my existence down to a keystroke. Dad — then a 15-year-old wayward teen who was stealing car radios and then selling them at the pub with his old man — was easily bored.

Having left school, one of his hobbies was breaking into phone booths around Melbourne and calling random people “just for a chat”.

One day my mum picked up the phone. He said he was taken by the sweet voice on the end of the line.

After two weeks of chat he asked her out, she said yes, they went tenpin bowling and the rest is history.

If the last number was an ‘8’ instead of a ‘9’ I wouldn’t be here. Dad’s English migrant parents weren’t violent with him, but it was clear he brought some serious emotional baggage into the relationship.

His mother left the family home when he was 12 — shacking up with another man and taking his younger brother. He felt abandoned by his mother and never got over that loss.

Dad inherited his volcanic anger from his mother. His father was a drunk — not violent.

Dad became violent living in St Albans in a broken household, where his parents just didn’t care what he did.

Regardless of his issues, Mum and Dad were in love and married at 18. They split up a few times in their early 20s but got back together before my older sister and I were born.

Growing up there was a lot of conflict between Mum, Dad and my sister.

Because of this I tended to lock myself in my room. Books, sport of any kind and homework were a kind of solace from the fights. My dad was a top detective in the AFP, which meant he worked a lot of overtime.

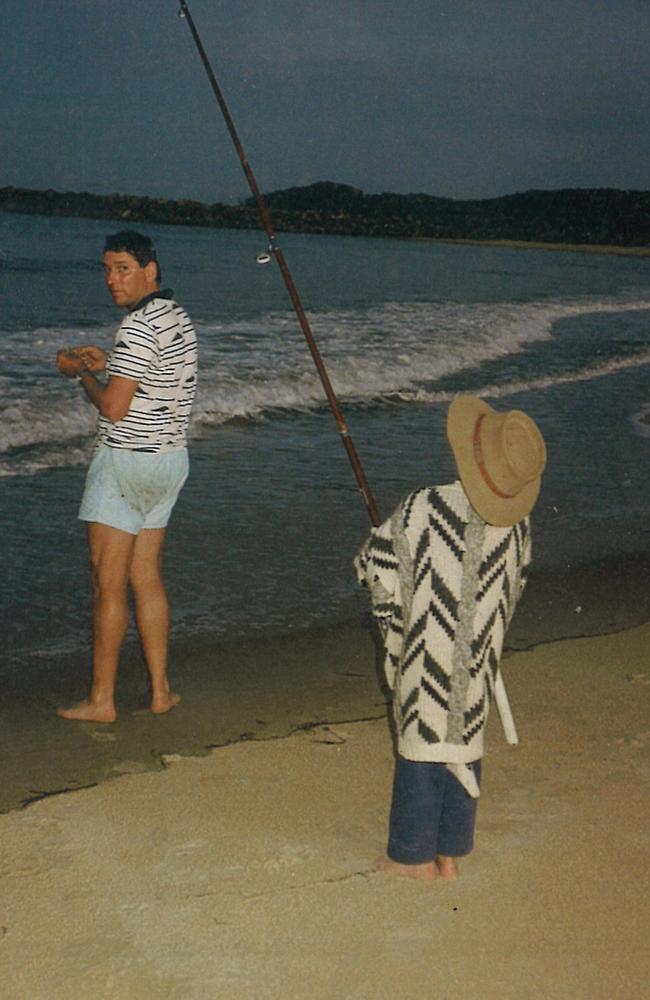

But he wasn’t a completely absent father. He was very engaged with my sport on weekends, encouraging me in playing cricket, soccer and tennis.

No matter how bad his hangover, he would always get up on Saturdays and take me to sport. He also spent a lot of time encouraging me to read and pushing me at school. I’m grateful to this day for that.

****

MY PARENTS’ separation began at my 18th birthday party when Mum accused Dad of hooking up with a family friend after he went up to the service station with her “to get some smokes”.

For the next few weeks there was almost constant fighting until my mother left the house. My sister had already left home so it was just my parents and me during this time.

Mum scratched his face and slapped him. Dad pushed her face into the couch and held her down, before throwing her against the wall.

I would learn later that a few years earlier Dad had, on two occasions, held a knife to Mum’s throat after he had been out drinking all night. I was 16 at the time but had no idea this was happening.

Two years after their separation, in October 2004, Mum would apply for what was the first of three AVOs against Dad.

Mum would later tell me that she planned to leave Dad when I was about 12. After Dad said he would take my sister and me away — threatening to use his contacts in the police — she relented.

****

WHEN Mum left home in February 2002, it was just Dad and me in the house at Pennant Hills.

It was then he started to really drink. Before he had been a high-functioning alcoholic, but the breakup tipped him over the edge.

My mates gave me a 4.5L Jim Beam bottle for my birthday. He drank that in about a week.

The house quickly turned into a pigsty; full of empty bottles, overflowing ashtrays and dust. The house stank of cat piss, cigarettes, dog hair and neglect.

It’s hard to describe how shattered, hurt and violent he was, especially after 2002.

He bashed down doors, smashed vases and screamed at me, Mum and my sister. He virtually stopped working.

In a fit of rage he destroyed my room, throwing the television through the window, pulling down shelves and smashing CDs.

He punched holes in my car windows with his bare hands, squeezed my balls and was inches from punching me at least three times. I don’t know what held him back.

I came home one day to see the majority of my clothes and possessions strewn across the driveway.

He would wake up at 11am and start drinking a few hours later. He would drink until the next morning before collapsing into bed. During his waking hours he would chain smoke and talk about Mum, going over their history; what went wrong.

He was convinced that my sister had been sexually abused — something she strenuously denies — and that Mum had turned us against him. He said I was a “liar”, “weak” and a “lapdog” for my mother.

Every time I walked up the driveway I would have a knot in my stomach, knowing I would be forced into a long and intense conversation.

I would sit there and listen out of a sense of loyalty, pity and fear.

He had made three suicide attempts before his 25th birthday, and had threatened suicide when I was living in Melbourne in 2002.

He would say to me every so often words to the effect: “Well, maybe I should just go and jump,” and “do you want me to kill myself?”.

It was hard to hate him because while he could be a complete tyrant, he could also be the softest, kindest and most loving father a son could wish for.

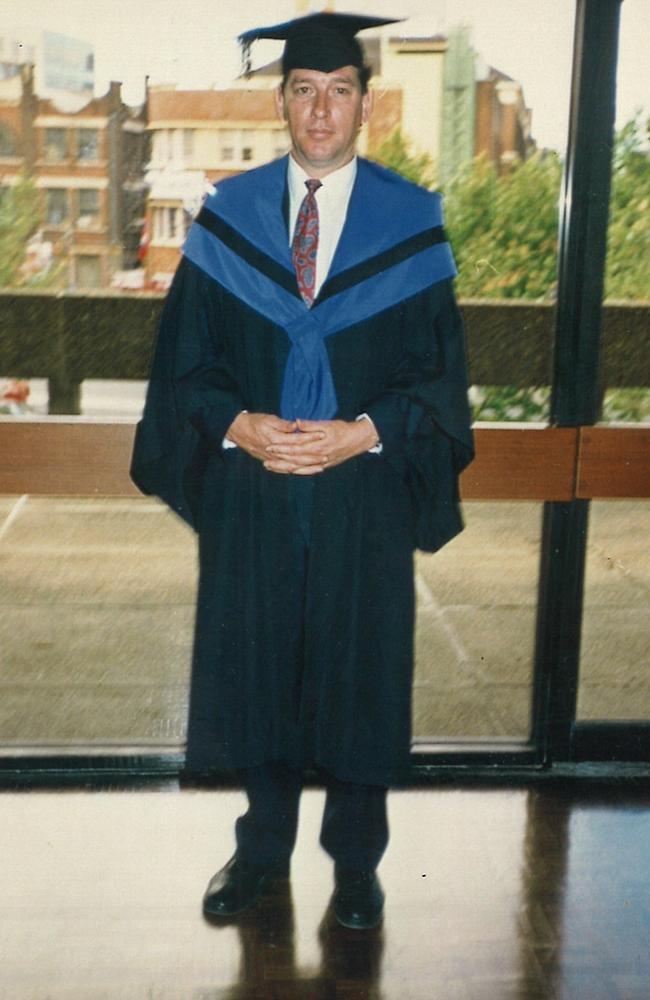

Dad went straight from being an AFP detective to joining the NSW bar as a barrister around 1995. He had good contacts in the criminal underworld — he defended Kings Cross identity Bill Bayeh, among others, in court — and so used these contacts to get him work.

His second career in law went in fits and starts, however, and so during stretches of no work he wrote his unpublished novel, Shadow of the Hangman.

He quickly became obsessed with investigating Mum’s life during their marriage. He would make inferences from phone calls, bank statements and diary entries — the vast majority of which were fanciful and delusional.

His gambling addiction (he once lost $10,000 on one bet), drug use (cocaine, cannabis and later, ecstasy), alcoholism and serial infidelity were all projected onto Mum. Writing was his weapon.

Dad never said he was delusional, although he did hint at it a few times. In a 28-page letter to my sister, he writes about the history of his marriage to Mum and his perceptions of it.

“Some of my interpretations may be mistaken because they are incomplete, or because my unconscious bias has tricked me into falsehoods that protect me from myself.”

This “unconscious bias” would soon destroy him.

I left home in early 2005, shortly after Dad’s girlfriend moved in.

She had worked alongside him in the AFP and their relationship became official six weeks after Mum and Dad separated in 2002.

Dad never said it to anyone in the family, but several of his friends confirmed he had been having an affair with her for a decade before my parents separated. They got married September 23, 2006, less than one year after Mum and Dad’s divorce.

While he got a sugar hit following the wedding, Dad soon slunk back into his old ways.

In 2007, he was named as a defendant in a second AVO taken out by my mother and sister.

He had been making threatening phone calls and had sent a letter to the Sex Crimes Squad requesting they investigate my sister’s so-called sexual abuse. My sister was floored.

“Not long after he had been served with the second AVO, on Wednesday April 25, 2007, Chris had an emotional breakdown and was in an extremely distressed state,” his second wife wrote in a later affidavit relating to Dad’s estate.

“Chris said ‘Please find me some help somewhere today where I can talk to someone and get some help’. I managed to arrange admittance to Mosman Private Hospital.”

This was the only time that Dad had been admitted for treatment, and the fact that he had wanted to take help was huge. I hoped it was a turning point. He was classic bipolar: when he was happy, he was the most incredible, charismatic and loving man.

When he was down, drunk, hung-over or high he was capable of utter cruelty. But nothing changed after he left hospital. He soon stopped taking his medication and went back to being his same old self.

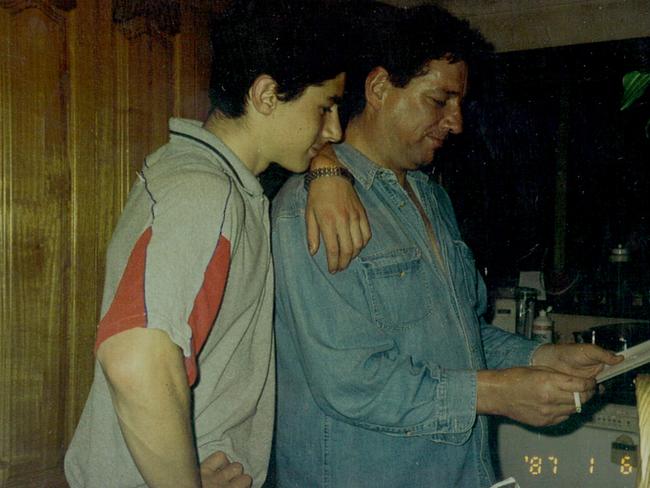

My relationship with Dad got worse from 2007 onwards. Frustrated that I wasn’t telling him what he believed to be true — and the fact that I wouldn’t instantly forgive him following yet another tirade of verbal abuse — he lashed out further.

Dad had contacted my university to try and revoke my degree, claiming that I had plagiarised.

After one particularly heated conversation between us while I was at work, he sent me a text: “your father died 20 minutes ago”.

I couldn’t believe it. But it was soon to get worse. Around the time Dad turned 53 he started to believe I was not his son.

He believed he had raised the offspring of one of his old police partners, saying that I had his eyes.

He said he’d still love me even if I wasn’t his, signing off one email to me in May 2008 with: “Your father (in fact or in spirit)”.

Before long I realised this wasn’t a phase — that he had come to believe his delusion that I was not his biological son. He refused to meaningfully engage with me unless I got a paternity test.

So I relented and we met up in Epping in July 2008. Dad was dishevelled and reeking. It was 11am and he would have already smoked five cigarettes by then. Or maybe he’d been up all night.

When I went into the GP’s office, he doctor told me: “You know you are being very indulgent, don’t you”? I agreed with him, but said that I hoped that science would help Dad see sense.

The $900 test came back a couple of months later and the result was as expected: I am, in fact, his son. He went silent after that.

Our relationship got no better

****

DAD and I had limited contact in the three months before his death. He’d told me that he wanted nothing to do with me so long as I refused to agree with his version of history.

On January 5, 2009 Dad sent a letter to the Healthcare Complaints Commission, making false allegations that Mum had a sexual relationship with a client while she was running her remedial massage business.

As a registered nurse, the accusation had the potential to ruin her career. He also said he was going to get her in trouble with the tax office for tax evasion.

Around January 20 he called me to tell me that Mum had been running a brothel for years.

He’d truly lost the plot.

Mum took out a third AVO against him and a few days later, on January 23, 2009, Dad sent me an email that gave me some hope.

“I am just very depressed. I drink and read over and over and then I fall apart,” he said.

“I think I might have to go to the hospital again. I’m going to get some antidepressants. I was served with another AVO. I didn’t contact the tax office. I just said that to hope for a way to find about (his daughter). (His friend) spoke to me yesterday and is very supportive. And (his wife) is very concerned. I don’t know what I’d do without her. Thanks for contacting me Ben. Maybe I’ll come into town tomorrow. Love Dad.”

Looking back on my response, it seems pretty flat. Apart from some texts to organise my visit to his place, this would be my last meaningful interaction with him before he died the following afternoon.

“OK. I think it would be best to see someone, Dad,” I wrote in an email a few hours later.

“Well, give me a call if you are able to come into town tomorrow. It would actually be easier if I was to meet you in Pennant Hills, as I’m going to be playing football Sunday morning. Ben.”

Maybe if I’d said “love, Ben” it might have made a difference.

The next day, January 24, I was at Pennant Hills shops and preparing to meet him at home.

I still hadn’t heard from him so I called his wife. She told me she had spoken to him when he was out but then he had turned his phone off.

Later that afternoon she called the police. The cops called me at 10pm to tell me the news: “Your old man is dead.”

****

DAD’S post mortem told a sad story: his 53-year-old body showed signs of emphysema, heart disease and fatty liver.

If he had died from any one of these conditions, at least his death could be categorised and understood. But death from suicide always feels like a chapter half read or a drink half finished.

As to why he did it, I think he felt guilty and couldn’t face himself over what he had done.

I don’t think he could ever tell me that he’d been having an affair for a decade — he’d told me the opposite for so long.

Underneath the anger and bluster, I think he felt worthless, ashamed and lonely.

I also think he couldn’t see how he could possibly repair his relationship with his kids.

In the years since his death I’ve learned a lot about mental illness.

One of the best bits of advice I heard was from Professor Ian Hickie during The Sunday Telegraph’s Can We Talk forum at the Campbelltown Catholic Club in 2015. He said that when someone is in a state of distress and refuses to seek help, saying that you will go with them is a very powerful thing.

Hickie said having someone by their side means that they don’t feel alone and are more likely to seek help. I look back on the number of times I told Dad that he needed to get some help, and can’t remember once ever saying that I would go with him.

Maybe if I’d said that it would’ve made a difference.

One of the most difficult things to swallow is that when he died he believed I had betrayed him, hated him and wanted nothing to do with him. Nothing could be further from the truth.

But it was impossible to have a relationship with a man who was so bent on destroying himself and everyone around him.

After he died I had mates come up to me and say that they had seen him at the Pennant Hills Hotel in the months before his death.

They told me he would be sitting there — morose, chain smoking and drunk — feeding thousands of dollars through the poker machines.

He’d hardly notice them, his glazed eyes sliding back to the pokies. He was nothing like the charismatic father they used to meet when they’d come over to my place. I was once so proud of him and to see him reduced to this was heartbreaking.

Since his death I’ve thought a lot about the countless times I was shit-scared of him and the lasting effect that has had on me.

I try to not see myself as a domestic violence victim, however, even though what happened fits that definition.

He slapped me around a few times but never bashed me. It was the grinding psychological abuse, his ability to belittle and intimidate and his explosive anger that were his most potent weapons.

There are people who have had it a lot worse than me and, in a funny way, that thought has got me through a lot of the most trying times. I was lucky in the sense that the worst of it happened after I turned 18, so I had some perspective. Mum has said since that the AVO system was flawed and had failed to protect victims.

She felt as if the odds were stacked against her. The first AVO was enforced for a period of 12 months, meaning the pattern of threatening phone calls and harassment at her work continued soon after the application lapsed.

She was reluctant to apply for further AVOs because she didn’t want to aggravate him anymore.

The second AVO was struck out in court and the third didn’t make it to court because Dad died 13 days before he was due in court.

She is disappointed in herself that she didn’t have him charged with domestic violence after they separated in 2002.

The police pursued her and urged her to press charges, but she says she didn’t follow up because of the implications for his career.

****

BUT all is not lost. Although Dad will never meet my daughter Maisie, who was born in November last year, he will have a hand in her upbringing.

His mistakes have become the landmines I want to avoid as a father. Drinking too much, working too much, neglecting your marriage and involving the children in parental arguments are the big wrongs I want to right with my own family.

Dad believed that if he had a successful career and worked hard, that his family would love him — despite his flaws.

Although I was proud of his achievements, what mattered to me was that he was home and in a good mood.

Unfortunately those two things became increasingly rare as the years went by.

But there is also a lot of positive stuff. He was a devoted father who wanted the best for me. He invested a lot of his intelligence, charisma, passion and strength in me, urging me to be the best person I could.

He had the forethought to praise effort over achievement, enforce discipline when necessary but give me independence as well.

He taught me how to be a man and, I’m discovering, a father. Nobody can take that away from him.

I just wish he was here, he was healthy and he could meet Maisie.