ADF soldiers left suicidal after drug trial demand Royal Commission

Ex-soldiers say the shocking rate of veteran suicides can be pinned on experimental drugs they were ordered to take.

NSW

Don't miss out on the headlines from NSW. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Veterans say experimental anti-malaria medications given to them by the Army are to blame for the shocking rate of suicide among ex-servicemen and women — and they are hoping a royal commission will back their claims.

Almost 3000 soldiers on deployments in East Timor and Bougainville between 1999 and 2002 were given the experimental drug tafenoquine or the registered medication mefloquine, dubbed this generation’s Agent Orange or “suicide pill” by some ex-soldiers.

Veterans say they were ordered to take the drug and not properly informed of potential side effects, including neurological problems, suicidal thoughts and nightmares.

“I was warned of digestive issues like vomiting and diarrhoea. I was told it was a safe drug, better than what was currently used, and that we were helping others by doing the drug trial to get this drug finalised approval,” says Toni McMahon, who was deployed to East Timor in the 1990s, before her posting in 2003 with the 5th Aviation Regiment.

Ms McMahon was given low doses of tafenoquine over three days before her deployment, with the drug administered once a week once she arrived.

The veteran said while the government would argue it had the consent of soldiers, Australian Defence Force (ADF) members “did as they were told”.

“Many of the drug trial guinea pigs, myself included, are now suffering a myriad of permanent health issues — that is of course, if they haven’t already committed suicide,” Ms McMahon said.

Ms McMahon said she suffered “full blown panic attacks” and suicidal thoughts.

“I now found it almost impossible to get out of bed in the morning. I could barely function during the day, I was always angry, snapping, raging, sometimes depressed, always bone-deep exhausted physically and mentally.”

Mefloquine, which is also known by the brand name Lariam, has been shown to cause neuropsychiatric side effects, including depression and hallucinations, and has been linked to a number of veteran suicides.

In fact, the World Health Organisation acknowledged in a research paper the severe neuropsychiatric side effects of the drug, more than 10 years before it was given to Australian troops.

But up until now, the Australian Defence Force has absolved itself of any wrongdoing and has not formally apologised to the veterans who say they were used as “human guinea pigs”.

“Despite the official government denials, these drugs are a well known cause of suicide in the veterans community,” says campaigner Stuart McCarthy, who retired from the Army in 2017 with an acquired brain injury after being exposed to both mefloquine and tafenoquine.

The US special forces command banned mefloquine after four soldiers who had taken the drug killed their partners and themselves over a five-week period in 2002.

THE EVIDENCE

Jane Quinn, a senior lecturer at Charles Sturt University, works with military veterans exposed to quinoline antimalarials, including mefloquine, to study neuropsychiatric conditions that arise from taking the drugs.

Originally from the UK, Assoc Prof Quinn’s husband, Major Cameron Quinn, was an officer in the British army and was given mefloquine during a training exercise in Kenya in 2001.

He suffered depression and nightmares immediately after taking the drug, before taking his life in 2006.

“The drug works against the malaria parasite because it’s able to cross the brain. Some individuals build up a higher-than-normal level of the drug within their brain and at that point it exerts a toxic effect,” Assoc Prof Quinn said.

“The theories are they (mefloquine and tafenoquine) cause the death of brain cells and we have a lot of scientific evidence to prove that.

“There are people who have fought for this country who have been severely let down by their government and medical system.”

The suicide rate among ADF personnel once returning from service was more than double that of the general population. Many former soldiers believe they have been incorrectly diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder or depression and were ignored by the military after raising concerns about the trials.

THE WHISTLEBLOWER

Major McCarthy, a veteran of six deployments, said the trials were “manifestly unethical” and suggested the ADF’s refusal to check the mental health of the participants was part of a cover-up.

In 2015 Major McCarthy, who served for nearly 30 years in the Army, broke ranks to condemn “a culture of denial, deceit and impunity” at the top of the Defence Force.

He alleged the ADF has downplayed the number of people who have been affected by the drugs and called for a royal commission to get to the bottom of the matter.

“We need a full royal commission, for proper accountability, so this is never allowed to happen again,” he said.

He said the commission would be able to investigate drug trials conducted by the military and Malaria and Infectious Diseases Institute, amid allegations of corruption and ethics breaches.

Defence has denied it acted unethically during the trials.

Labor has also backed the calls for a proper investigation.

“While Labor would welcome an apology from Defence to these veterans, we know some have experienced mental health issues and Labor wants to see practical support,” said Shadow Minister for Veterans’ Affairs and Defence Personnel Shayne Neumann.

“This is why Labor has called for a royal commission into veteran mental health and suicide and this is precisely the type of issue we think should be considered by a royal commission.”

Reflecting on her military service 20 years on, Ms McMahon said she “wishes she had said no” to participating in the trials.

“I just didn’t realise at the time that I had a choice (and) that I could make my own decision and not just jump on command as I had been conditioned to do,” she said. “I trusted the Army and believed that they would look after me, that they cared about me and anything they needed to do would be in my best interests.”

The government last week voted to support a Senate motion for a royal commission into veteran and defence suicide. Prime Minister Scott Morrison and cabinet will determine the next steps.

It comes after the federal government last year announced a National Commissioner into Defence and Veteran Suicide with an ongoing role in investigating individual cases of suspected and attempted suicide.

‘DEFENCE FORCE STOLE MY HUSBAND’

Dave Whitfield has spent nearly 20 years of his life waking up from nightmares and enduring severe seizures up to five times a week.

The veteran served in the Army between 1997 and 2004 and was deployed to East Timor in 2001 as a medic. His wife Alison says he spends every day feeling “responsible” for handing the deadly mefloquine drug to his mates, some of whom have passed away.

Distraught and at breaking point, Ms Whitfield said her husband was not told before he was deployed that he would be “handing out or taking mefloquine”.

“At night he has nightmares, sometimes reaching the point of him punching the bedhead, shaking and sweating,” she said.

“He only sleeps for two hours because of the pain and his mood swings are on a daily basis.”

Mr Whitfield, 48, says the drug “destroyed” his life.

“My speaking, hearing and eyesight are also badly affected plus so many other things too numerous to mention,” he said.

“The untried drug they tested us with has killed so many of my mates through suicide, the ones who are still with us are all distant shells of the once fit proud young men and women.”

Ms Whitfield said her husband’s body is similar to that of a 90-year-old and added that veterans and their families deserve the ADF to acknowledge and take responsibility for the trials they oversaw.

“The ADF stole my husband, they stole a father of five, they stole a son, a brother and a mate in the army,” she said.

“But the ultimate theft was they stole a life from a man willing to give up his, so they and their loved ones could have a better one.”

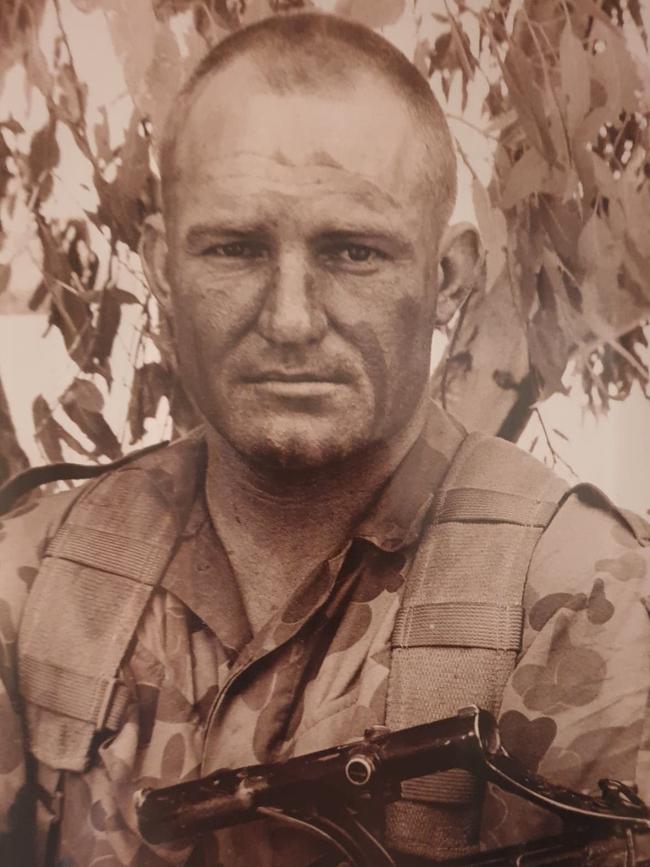

SOLDIERS FIGHTING THE SIDE EFFECTS EVERY DAY

“Something was not right”

An East Timor veteran suffering long-term health issues after taking part in controversial anti-malaria drug trials, says he feels betrayed by the Australian Defence Force.

Wayne Karakyriacos said soldiers did not give informed consent to participate in the trials. He said the drugs have had a major detrimental impact on their lives, as they struggle both mentally and physically.

“Coming home I knew something wasn’t right in a matter of days. One day I remember waking up in the morning and my wife wasn’t in the room,” he said.

“I panicked and looked for her before finding her in the opposite room.

“She screamed when she saw me and was crying.

“She said that I had been punching her while not making any noise. I was horrified and she knew something wasn’t right. My anxiety started kicking in and I struggled.”

“If I had this opportunity again, I would have never participated in this drug trial.”

Every day Christopher Ellicott lives with the regret of taking part in a drug trial that caused his life to “spiral out of control”.

Prior to deploying to East Timor more than 20 years ago, Mr Ellicott was told he would be taking part in a drug trial.

“The manner in which this was told to us still makes me very angry to this day,” he said.

“We were informed that the drugs we were being trialled on were mefloquine and tafenoquine — although, we were not provided the knowledge of which of the two drugs we were taking.”

He suffered side effects including chronic fatigue, chronic diarrhoea, complete loss of appetite, nightmares and black urine. He discharged in 2004 after his symptoms worsened.

“My life continued to spiral out of control,” he said. “My life became more devastating with the high number of ‘post malaria trial’ suicides with the men and women that I served with. If I had this opportunity again, I would have never participated in this drug trial.”

“Everyone affected by these drugs want answers”

More than half of Colin Brock’s army unit have had their lives destroyed by the anti-malaria drugs that were given to them by the army.

Mr Brock, who joined the army in 1990, was given the drug in 2000 before his deployment to East Timor. Mr Brock said he suffered “uncontrollable anxiety and anger” and was eventually admitted to a psychiatric hospital in 2016.

“Everyone affected by these drugs want answers. My section in East Timor consisted of nine fit men, six out of the nine are now experiencing all of the symptoms and are unable to work,” he said.

“I personally have been to two funerals as a direct result of these horrendous drugs and I bet if no help is given, they won’t be the last ones.

“It wasn’t until I got out of the army that everything went south”

Desmond Rose says he was forced to choose between taking the antimalarial drugs or risk not being deployed with his battalion.

The veteran served in East Timor in 2000 and 2001, where he was placed on both mefloquine and tafenoquine drug trials.

“Over the years I thought I was mentally fine, but the real truth was I had changed since returning from Timor,” he said.

“Some days I am fine and others I am mentally messed up. It’s so hard with work because I feel like I’m not good enough and need to be reassured all the time.”

Lifeline: 13 11 14

More Coverage