Arguing about whether students with autism need separate schools is highlighting a volatile education issue

PAULINE Hanson’s comments on autistic children have highlighted a volatile schools issues, writes Bruce McDougall.

NSW

Don't miss out on the headlines from NSW. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- Hanson suggests autistic kids be removed from mainstream schools

- Constantly suspended autistic children being ‘denied an education’

PRINCIPALS say their staff are being injured at “alarming rates” in the state’s schools and they are struggling to keep teachers and vulnerable students safe.

As the NSW government basks in a $4.5 billion surplus, a human crisis is unfolding in classrooms born of woefully inadequate resources, too few troops and often non-existent support.

Many teachers working at the toughest coalface in public education — with children of high needs or extreme behaviours — are “overwhelmed and physically exhausted” due to the lack

of support, school leaders have revealed.

They have told a parliamentary inquiry of a serious shortage of places and resources for students with learning and behaviour problems in special schools and in support units in mainstream schools.

As a result, children with disabilities or special needs can be put into classes with

a teacher who is not sufficiently qualified.

And as a growing number of students with diverse issues are integrated into mainstream classes, teachers increasingly are finding it difficult — if not impossible — to cope, even with extra help.

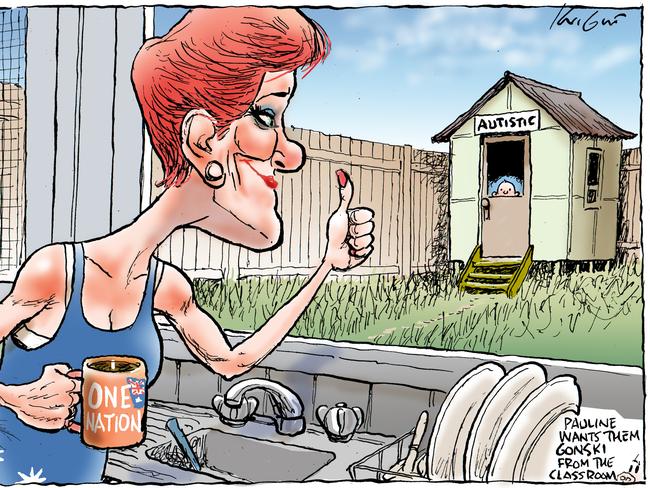

One Nation leader Pauline Hanson ignited an emotional debate this week when she suggested autistic students should be removed from mainstream classes to stop other children being held back.

Hanson’s comments in the Senate drew a torrent of criticism as they touched a raw nerve in families and educators over the highly sensitive issues around the placement of children with special needs.

The South Western Primary Principals group, covering more than 70,000 students with a high number from a non-English speaking background and rising numbers with a disability, reveals children in need are “constantly missing out on appropriate placements” because of a lack of vacancies.

But no waiting lists are compiled so the true extent of the number of students missing out on a place of their first choice is concealed.

The primary principals have told the inquiry: “Parents are sometimes forced to accept enrolment placements that they know are not sufficient for their child due to a lack of special placements available. At times a child’s safety may be at risk due to an inappropriate placement.”

The secondary principals say the shortage of places greatly affects children with behaviour problems.

“Where an access request has been made and no placement is available there is rarely follow-up support offered,” it says.

“The demands on school learning and support teams have escalated over the past five years as more students present with special learning needs.”

Adding to the teachers’ burden, according to the NSW Secondary Principals’ Council, is another disturbing trend.

Parents who become “serial and unrelenting complainants” are seriously affecting the mental health and wellbeing of staff.

While the principals acknowledge the right of parents to be heard, they say “serial complaining is proving to be an incredible burden on schools … often to the detriment of the other students enrolled”.

Parents not satisfied with a school’s responses often escalate the issues to higher levels of the Education Department.

When that fails they take it to ministers and MPs from whom teachers receive a “please explain”.

“They (complainants) often go to a public forum or social media where they denigrate schools and teachers with impunity,” the principals say in a submission to the parliamentary inquiry.

In a NSW Primary Principals’ Association survey 74 per cent of heads of special schools and support units indicate they do not have enough staff.

“Teachers are frustrated that their day mainly consists of keeping people safe — teaching and learning becomes the lowest priority,” its submission says.

“Many of our students are violent and need several people to manage one student which puts disadvantage across the whole school.”

In the special schools catering for children with the highest needs, staff, students and parents are trapped in a “cycle of crisis management”.

The primary principals say the increasing number of students with disability and special needs presenting for enrolment in government schools is presenting special challenges.

The NSW government, which is ploughing a record $2.2 billion into building 120 new schools or upgrades to counter surging enrolments, has told the inquiry an extra 124 specialist support classes have been made available this year.

About 72 per cent of all school students with disability in NSW are supported in government schools.

Smithfield Public School in Sydney’s west, which runs seven support classes catering for 73 children with a wide range of disabilities, from autism to multiple sclerosis, paints a grim picture for the parliamentary committee.

Submission author, and Smithfield principal, Cheryl McBride says 90 per cent of teachers surveyed said state therapy services for children with special needs are “non-existent”.

In the early intervention unit counselling time has been halved to one day a week to assess up to 32 students with special needs.

At Smithfield students with disabilities or special needs who are in mainstream classes and inadequately funded “struggle with all aspects of school life”, Ms McBride says.

“Some children at Smithfield Public school have waited for extensive periods of time for placement in a supported facility.

“The effect of waiting is devastating for the child’s esteem and achievement. The impact on other students in the class can be major.”

The South Western Sydney Principals’ group agrees many children with disabilities wait for extended periods for placement in support classes.

“The inappropriate long-term placement of special needs students also has a negative impact on all other students enrolled in the regular class,” it says.

“While students with disabilities should be welcomed in the mainstream setting, there are some cases where a specialist setting would be far more appropriate.

“Parental choice should not be the final determining factor, as a mainstream setting cannot offer.”