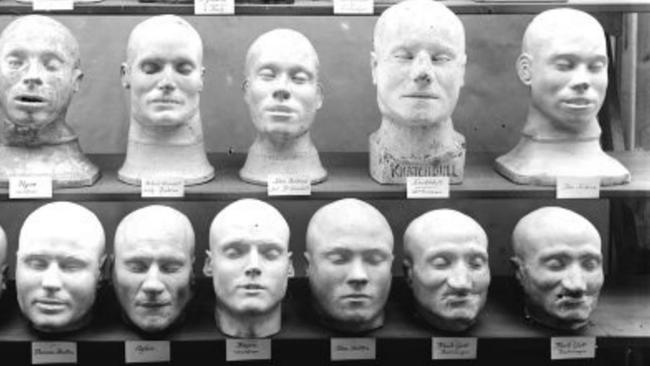

What happened to these 19 Australian death masks?

A ROGUE’S gallery of killers, bushrangers and convict rebels, this macabre display of death masks was a who’s who of early Colonial crime. So what happened to these 19 death masks?

NSW

Don't miss out on the headlines from NSW. Followed categories will be added to My News.

A ROGUE’S gallery of killers, bushrangers and convict rebels, this macabre display of death masks included the faces of Sydney’s most notorious early criminals.

Cast from the corpses of hanged men and villains shot dead in gunbattles, all that remains of the collection once held at the Australian Museum is this curious 1860 photograph.

So what happened to this grim cast of characters and why were we so fascinated by their heads?

OUTLAWS, MURDERERS AND REBELS

Dating back to the earliest days of the museum, a visitor in 1838 described the collection as featuring “the faces of the biggest criminals in the Colony”.

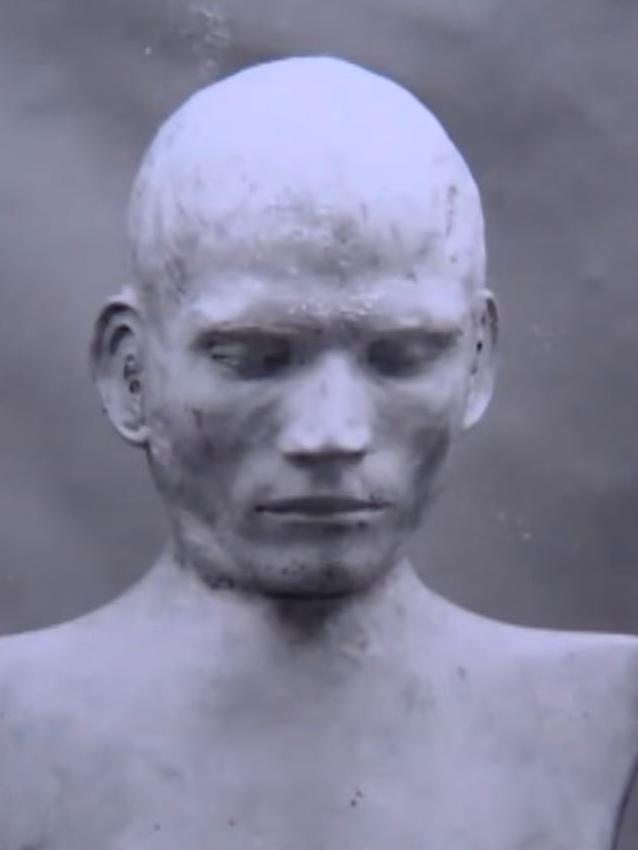

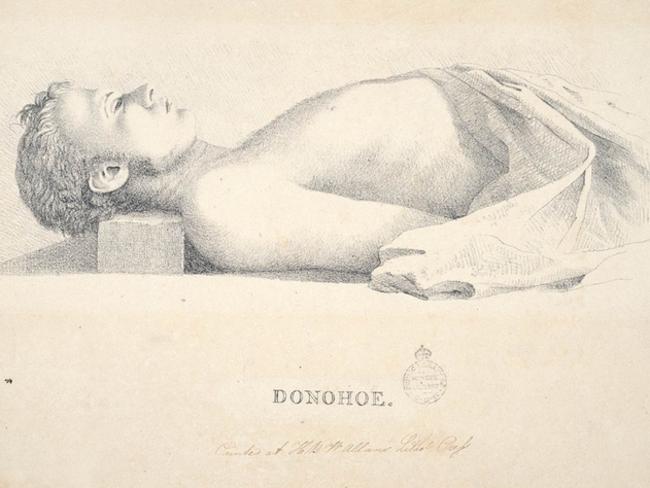

There was the mask of famed bushranger Bold Jack Donohoe, immortalised in the ballad The Wild Colonial Boy, whose gang roamed Sydney’s west plundering “Robin Hood” style.

In 1830, Donohoe made his last stand in a gunbattle with mounted police near Campbelltown where he was shot and killed and “thus the Colony rid of one of the most dangerous spirits that ever infested it,” wrote the Sydney Gazette.

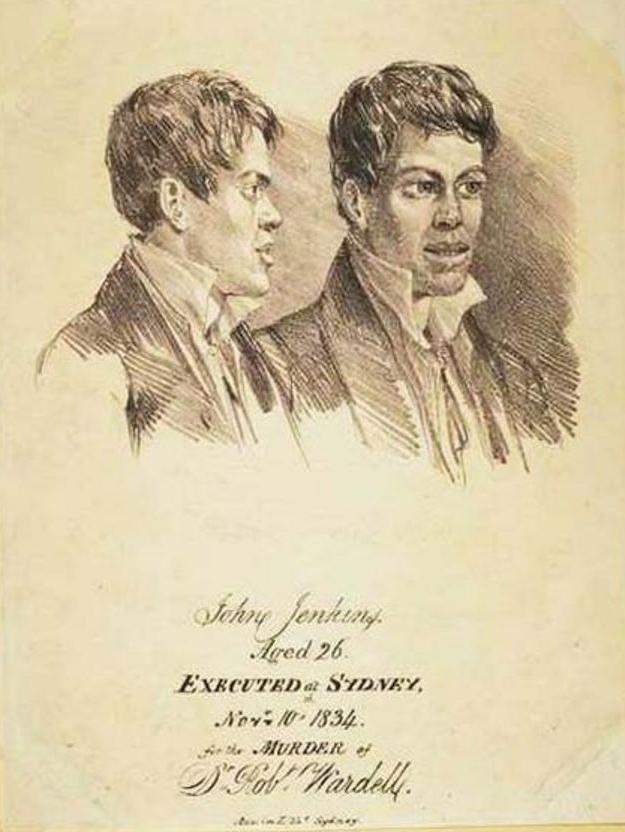

The collection also included the grotesque masks of “Black” John Goff, ringleader of the first convict rebellion, and murderer John Jenkins, who was executed for the sensational murder of newspaperman Robert Wardell in 1834.

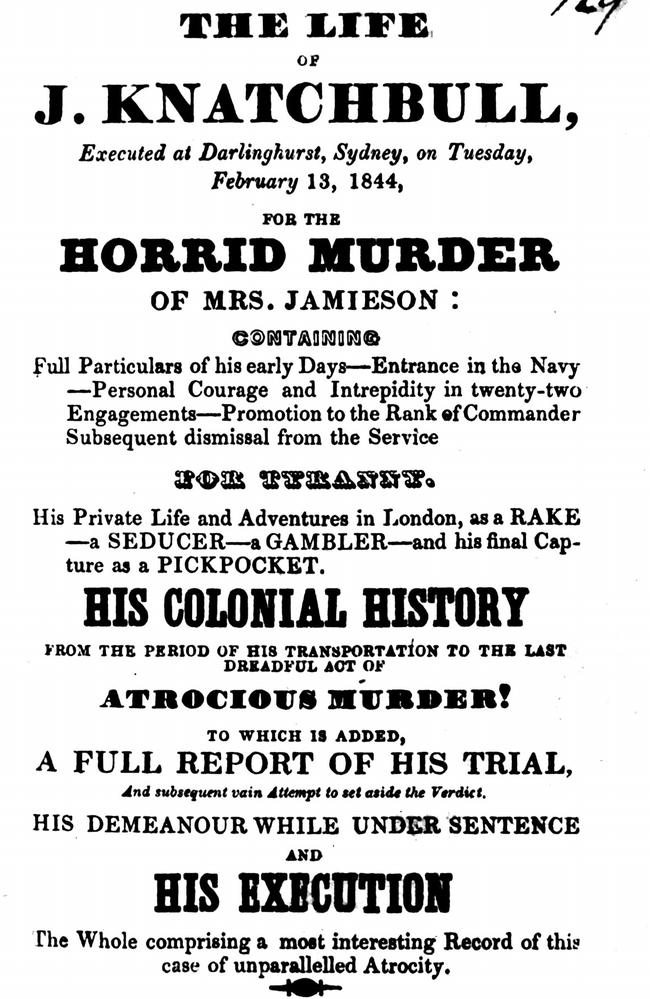

Over the years, it grew to include wretches such as John Knatchbull, a former naval captain who bludgeoned an innocent shopkeeper, Ellen Jamieson, to death with a tomahawk in 1844.

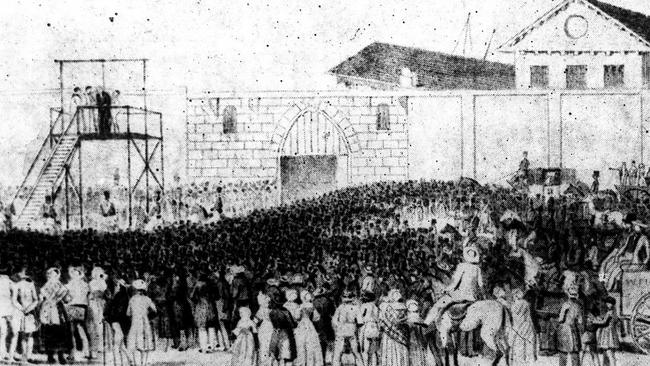

Knatchbull’s senseless, random crime shocked Sydney and a crowd of 10,000 turned out to see him executed at Darlinghurst Jail, the biggest public hanging of the time.

MORBID CURIOSITY

The practice of making death masks was widespread in the 19th century and the public flocked to museums after a hanging to see the heads of dead criminals fresh from the scaffold.

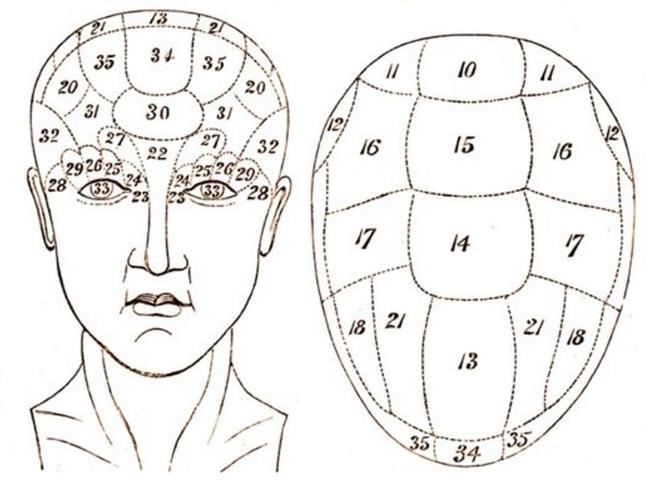

It was the hey day of phrenology, a pseudoscience which claimed to explain a person’s characteristics and traits through the bumps and depressions of the skull.

While famous people were of interest, it was the heads of criminals that were hotly sought after by phrenologists. And with a large population of convicts and ex-convicts and about 80 hangings a year, Australia proved a rich vein to mine.

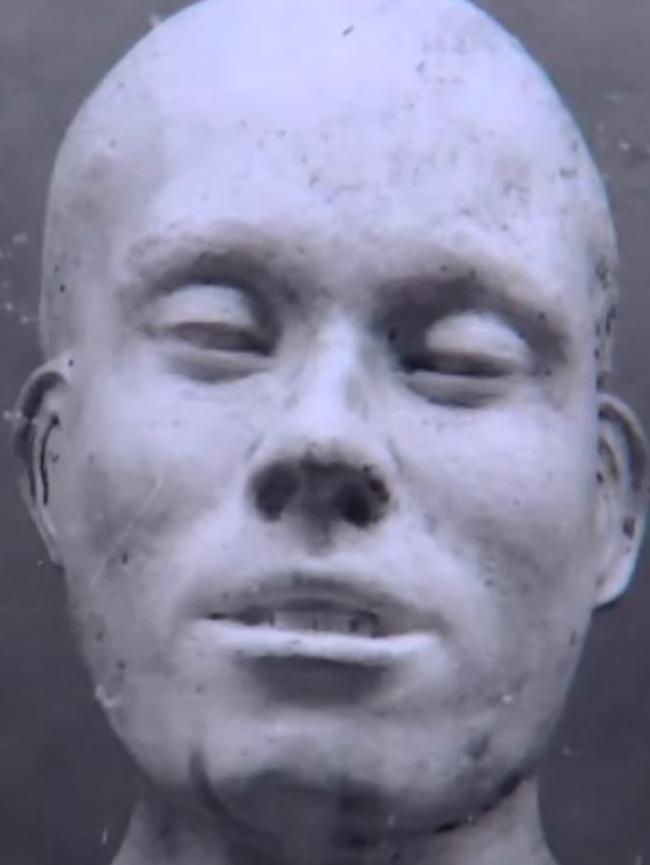

Many criminals became unwitting contributors to phrenology, their heads shaved and greased immediately after death and plaster applied to create their three-dimensional portrait.

Australian Museum collection officer Dr Stan Florek said phrenologists believed the structure and morphology of the skull would prove the existence of a criminal type.

“By studying the skulls of criminals who were executed, they thought they could work out what a criminal skull looked like. Of course it didn't work,” he said.

A MORBID COLLECTION

On December 5, 1893, the museum sent the collection of death masks to Professor Anderson Stuart at Sydney University’s Medical School.

The exchange was to remain “open” in case the museum wanted anything from the school in the future. And there the trail runs cold.

Dr Florek said the museum still holds countless curiosities from the time but the death masks in the 1860 photograph were its last.

“The museum was considered a potential repository for all sorts of interesting things,” he said. “Anthropology always had this branch of the natural study of humans, from a biological perspective if you like, so the little things that trickled into our collections were skulls and body parts.

“The masks fall under that area of curiosity and in some ways, (show) emerging science before a more evidence-based and more rational approach to studying humans. They tell us more about the history of our misguided thinking.”