A ‘monster’ killer’s vow to kill his demons in letter to his victim’s partner

Inside the radical jail program aiming to turn killers, thugs and armed robbers into productive members of the outside world by confronting their egos, bravado, and their crimes.

NSW

Don't miss out on the headlines from NSW. Followed categories will be added to My News.

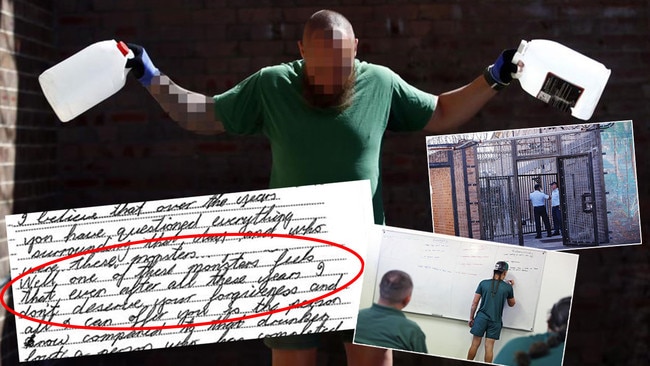

A self-confessed “monster” who murdered an innocent man in an “attack of savagery” has pleaded with his victim’s ex-partner for forgiveness, vowing to never again drink or take drugs.

In a letter obtained by The Sunday Telegraph John (alias) tells the family he is ashamed of his life after stabbing a man to death in a boarding house in 1997.

“I had become reckless and was leading an impoverished lifestyle and sadly, regrettably, on that day … I wrecked numerous lives and shattered people’s worlds.

The killer made three promises to the victim’s family – never to drink, take recreational drugs, and to stay on prescribed medication for the rest of his life.

He also concedes he deserves to be hated, and doesn’t expect the family to want any contact with him.

“I believe that over the years you have questioned everything surrounding that day and who were these monsters.

“Well, one of these monsters feels that even after these years, I don’t deserve your forgiveness and all I can offer you is the person now, compared to that drunken lout, a person who has completed many courses/programs over the years.”

After decades in prison and finally on parole, the convicted killer says he now detests violence and credits his long stint in jail with his own redemption.

Sunday Telegraph journalist Jessica McSweeney was granted exclusive access to Long Bay Jail, to witness how a prisoners program can turn killers with self confessed “ego and bravado” into productive members of society in the outside world.

The Violent Offenders Therapy Program takes offenders of the most violent of crimes, including murder, grievous bodily harm and armed robbery, and forces them to confront their triggers and motivation to commit acts of violence.

This offender, like many others, joined the Violent Offenders Therapy Program as a pathway to parole after decades in jail, but ended up leaving with what he says is a genuine change in behaviour and beliefs.

Drugs, associating with friends from his criminal past, and giving into his anger are all triggers John learnt to see in himself and counteract through his time in the VOTP.

“For example, I’m in McDonalds and a few teenagers push in front of me. In yesteryear I would have said something, argued and it would have flared up. But the person I am now, I just smiled to myself and thought ‘If only they knew how far I’ve come’,” the offender said.

“I was full of false bravado and an inflated ego and drinking alcohol at the time [of the crime],” the offender said.

“I’m now holding myself accountable towards my emotions, I detest violence now, I don’t believe there is any room for violence in society, there’s no need for it, it’s draconian and that caveman mentality.

“It took a long time for me to arrive at this and let all that false bravado and ego go.”

Naturally, listening to John’s story comes with scepticism.

In the judgement notes for the crime, the judge noted John and his co-accused slashed their victim multiple times after he yelled at them to turn their radio down.

The slashes went so deep as to leave cuts in the man’s ribs, and his heart and liver were pierced.

He died in hospital while undergoing emergency surgery.

As a young man guilty of murder he was desperate to get out, unsuccessful in appealing his conviction and still full of anger.

Despite his obvious capacity to commit heinous acts of violence, John and his post-prison psychologist Fiona Mason both believe he is now a changed man.

“A lot of these guys have used violence to gain power, its been instrumental to gain drugs and its also expressive violence where they have limited capacity to manage emotions and violence erupts,” Dr Mason said.

“It’s all about learning to use strategies other than violence.”

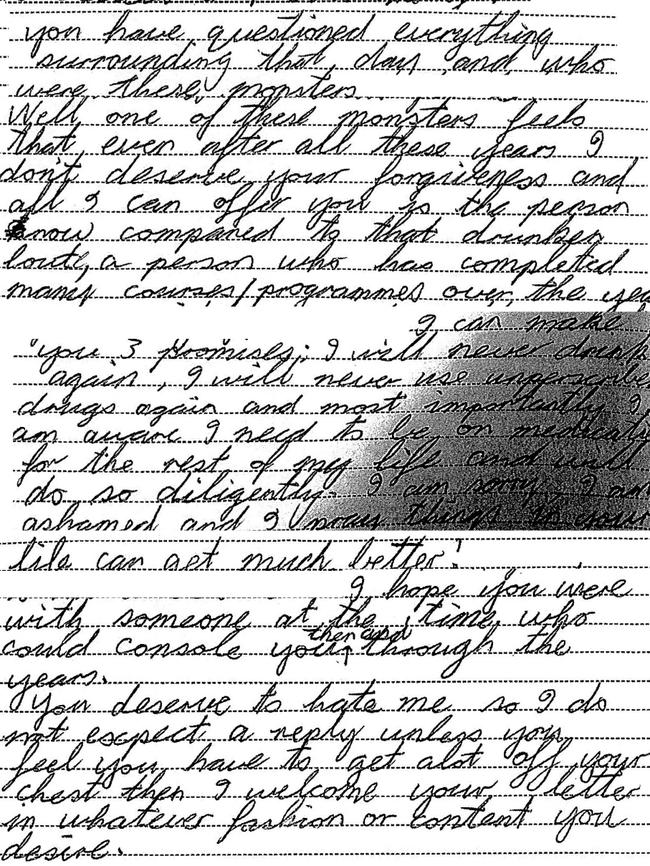

A handful of inmates just like John are gathered in a small classroom like room with a whiteboard and mismatched chairs set in a circle when The Sunday Telegraph is invited to see a session first hand.

The VOTP program takes the inmates through an extensive year long set of modules, but on this day the prisoners are on the ‘thoughts and feelings’ lesson.

Jailhouse psychologist Sheridan Walsh sits across from the inmates as they discuss a scenario where expressive anger could lead to another explosion of violence.

She sets up the scene – “you are walking down the street and you see your mate across the road,” she says.

“You wave and say hello but he ignores you and keeps walking.

“What do you do?”

First they identify and go through the thoughts that come up.

An inmate covered in tattoos and cross armed says: “maybe they didn’t see you”, another jumps in straight away “I would think ‘who the f**k are you’”.

Another: “You ignorant c***”.

Then the feelings that come along with those thoughts. The men shout out: “confused, angry, disrespected.”

Then the behaviours that would come from those thoughts and feelings? An inmate writes on the board: “act aggressively, confront them”.

Ms Walsh then asks the inmates to use some of the counter-strategies they learn in the program to rethink the scenario – giving the person the benefit of the doubt, logically thinking through where there actions could land them.

The inmates decide the best response would be to ignore it and phone the person later.

In the rapid fire session, psychologists encouraged the prisoners to read out scenarios and negative thoughts and respond with ways to de-escalate.

“They deserved it,” one prisoners reads out.

“No one deserves it, and who am I to enforce anything, no one deserves harm,” another inmate counters.

In talking through scenarios where the inmates might choose violence, they are encouraged to brainstorm different responses – from simply walking away to using words instead of fists.

Psychologists want the inmates to come up with simple “counters” for dangerous scenarios and thoughts so when they come across them on the outside, they already know how to respond.

“The police are harassing you,” another calls out.

“I should just use assertive communication … they have families and they have a job to do,” another inmate responds.

When being considered for parole, the inmate’s progress in the VOTP is taken into account, and although the ongoing maintenance sessions are voluntary, for some it can be a condition of parole.

CONFRONTING THEIR CRIMES

One of the key parts of the program is the offence mapping exercise.

Psychologists force the inmates to confront in forensic detail their crime, who it hurt, why they did it, who they were as a person at the time.

One current inmate who is serving prison time for assault and break and enter said the program can become tense when the violent criminals are forced to look inside themselves.

“It gets heated,” he said.

“When I first came in I was only doing it for parole, but I’ve learnt so much with each module.”

“Before I just did things because I wanted to, but now understanding why I did them has been a huge thing, I’ve learnt a lot about myself.”

To give the violent offenders the best chance of success they are separated completely from the other inmates, they have their own wing of Long Bay complete with a small outdoor exercise area and the same drab, cold cells as the rest of the prison.

All the inmates in that wing are doing the same program, and can support each other in and out of the classroom.

LIFE BEYOND JAIL WALLS

Outside the walls of Long Bay, John knows he will always be haunted by his crime, and will not be able to ever make it right with the man he killed.

After decades in jail he is learning how to live in the 21st century, complete with self serve check-outs and smart phones.

The world he left behind as a young man thrown in prison is long gone, and he says, so is the old John.

“I’m happy, I’m in a good place, I’m looking at doing a diploma in counselling specialising in alcohol and other drugs,” he says.

This doesn’t mean John has free rein in the community – he attends monthly group meetings with other VOTP graduates and is in weekly contact with his psychologist.

He knows many won’t be able to see him outside of the crime he committed, but John says he still wants to try.

“I look at violence in a totally different way now, and I can attribute a lot of that to the VOTP.”