For a brief moment last year Australia had the Prime Minister it deserved when Malcolm Turnbull stood up to newly elected US President Donald Trump.

“This is a killer … this is the most unpleasant call all day. Putin was a pleasant call. This is ridiculous, this is crazy,” Trump fumed down the phone to Turnbull.

He was unhappy with the deal his predecessor Barack Obama had struck to take 1250 asylum seekers from Nauru and Manus islands.

He was branded “Mr Harbourside Mansion” and said he preferred his own Point Piper mansion to the Prime Minister’s traditional residence

“There is nothing more important in business or politics than a deal is a deal … you can certainly say that it was not a deal that you would have done, but you are going to stick with it,” Turnbull told him.

At a time of uncertainty the world took hope from the tough, no-nonsense Aussie.

“That was Turnbull’s finest hour,” Australian National University political analyst Dr Norman Abjorensen says.

“He stood his ground.”

But he could not bottle the lightning and repeat the same magic on the shifting sands of his divided party at home.

Having taken the prime ministership in a coup from party leader Tony Abbott and then run a disastrous election, where the Liberals retained power but lost ground, he has had to contend with the same plotting and niggling from within the party that brought him to power in the first place.

“I am not sure that we ever really got the chance to see Malcolm Turnbull at his best. He never had the room to develop into the leader he could have been,” Abjorensen says.

Like many who know Turnbull personally, Abjorensen says the hope that came with Turnbull securing the top job was quickly tempered by a harsher political reality.

“Most of us have watched his time in office with disappointment,” he says.

Turnbull was increasingly hamstrung in his efforts to appease the conflicting elements in his party.

“He has become a figurehead of a small ‘l’ liberal leading an increasingly conservative party,” Abjorensen says.

Turnbull confirmed as much on Thursday when he said: “What we have witnessed at the moment is a very deliberate effort to pull the Liberal Party further to the right.”

The former lawyer and wealthy businessman entered politics on a wave of optimism and promises on climate policy. His time in Canberra has seen those values and that man steadily eroded.

Turnbull won a bitter preselection campaign in Wentworth against the highly regarded incumbent Peter King, splitting Liberal voters and being accused of branch stacking and using his considerable wealth to win the seat.

In 2008 he seized the leadership of the opposition Liberal Party from Brendan Nelson, winning by four votes.

Yesterday, Nelson confined his comments on the man who toppled him to his current role as head of the Australian War Memorial and praised Turnbull’s “support” for the Memorial’s expansion.

“Without his support, there would have been no prospect for detailed planning for this now well-advanced major investment,” Nelson says.

With the backing of Turnbull’s successor he “will have left a major, enduring and meaningful legacy for Australia”.

Not exactly the legacy Turnbull had in mind.

“I think he would like to imagine his legacy is an economy running smoothly, job creation and innovation,” Professor Carol Johnson of the University of Adelaide says.

“History will see him as a bit of a disappointment.”

The first disappointment as leader was going to town on then prime minister Kevin Rudd and treasurer Wayne Swan in 2009 for doing deals for Labor mates under the OzCar scheme.

Turnbull came unstuck when it emerged the treasury official who had supplied the documents, Godwin Grech, had forged them.

In November 2009 Turnbull, true to his early ideals, backed Labor’s carbon pollution reduction scheme.

One week later Tony Abbott challenged him and wrested the leadership from him by just one vote.

The same issue and the same man came back to haunt him this week.

Turnbull made a clear dig at Abbott on Thursday when he said he would not stay in Parliament if he was rolled.

“I’ve made it very clear that I believe that former prime ministers are best out of the Parliament. I don’t think there’s much evidence to suggest that that conclusion is not correct,” he said.

At the same time he also made it clear that he valued revenge over the party. Not surprising for a man who dabbled with the Labor Party before joining the Liberals. It was never about the politics, it was always about Malcolm.

After Abbott took power, Turnbull felt he had more to offer and decided to stay in politics. He took the job of communications minister in Abbott’s government and was responsible for the roll-out of a limping alternative to Labor’s National Broadband Network.

Today the cost of the delayed NBN service has blown out and created a digital divide between those with high-speed broadband and others struggling with slow, old-school copper phone wire.

Turnbull himself said he had inherited a “calamitous train wreck” from Labor.

“As I often used to say, in the words of the Irish barman when asked for directions to Dublin, ‘If I were you I wouldn’t be starting from here,’ ” Turnbull joked at the time.

Meanwhile, the embers of his leadership ambitions were waiting for the right political wind to fan them back into life. A failed leadership spill against Abbott in February 2015 merely set the scene for him to seize back power by 54 votes to 44 in a leadership ballot in September the same year.

“The Prime Minister has not been capable of providing the economic leadership our nation needs,” he said at the time.

The only son of a hotel broker and a radio actor, who split up when he was nine years old, had achieved what he told his schoolmates he would and entered The Lodge as the Prime Minister of Australia. The question was whether he could do what he said Abbott could not.

“For the first three months after he deposed Tony Abbott all lay before him. The Australian public was in the palm of his hand,” University of NSW political researcher Dr Mark Rolfe says.

“Then he stuffed it up.”

Turnbull, a Rhodes scholar, who had been Kerry Packer’s barrister and defended former MI5 officer Peter Wright during the Spycatcher case, knew about public life. His time as head of the Australian Republican Movement during the failed referendum had taught him plenty.

His wife Lucy, mother of their two children, is a former Sydney mayor and heads the Greater Sydney Commission.

She has provided steady counsel on the machinations of politics and herself attracted worldwide attention when French President Emmanuel Macron described her as “delicious” during his recent visit to Australia.

Turnbull may not be in tune with the right of his party or the average Aussie but he and his wife are loved in his well-heeled eastern suburbs electorate of Wentworth.

His financial success has been used against him. He was branded “Mr Harbourside Mansion” and was pictured paddling his kayak on the Harbour after saying he preferred his own Point Piper mansion to the Prime Minister’s traditional residence, Kirribilli House, on the other side of the bridge.

After admitting to a $1.75 million donation to his party last year, he rounded on Labor leader Bill Shorten. “He says I’m Mr Harbourside Mansion. I do live with Lucy in a nice house on the water in Sydney. Yes, we do. And we paid for. We pay the expenses on it. We pay — that’s our house.

“Bill Shorten wants to live in a Harbourside mansion for which every expanse is paid for by the taxpayer. That’s the big difference.”

In 2016, when the Senate rejected the bills to reinstate the Australian Building and Construction Commission, Turnbull called an election.

“He made political mistakes in the 2016 election campaign. He called it too early, it ran too long and his message did not cut through to the electorate,” Johnson says. He was returned to power with a one-seat majority.

That slim majority and constant battle to get bills through the Senate required all of Turnbull’s negotiating skills to get things done.

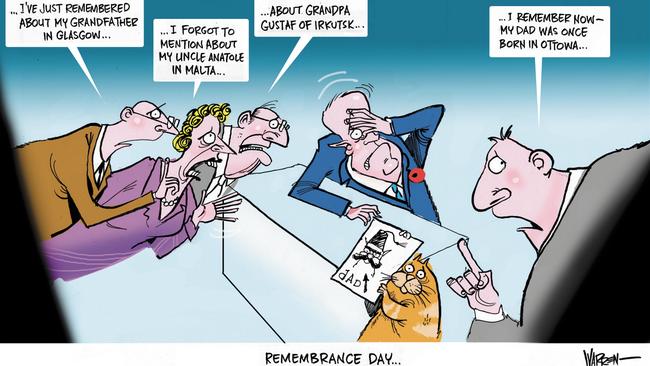

At the same time the house was dogged by the Section 44 eligibility crisis.

Despite this, he held the same-sex marriage plebiscite, in which 61.6 per cent of Australians voted Yes.

On 7 December last year, same-sex marriage was legalised, securing possibly Turnbull’s greatest legacy.His critics on the right of his own party were not impressed.

Energy blackouts in South Australia and soaring energy prices also brought back the spectre of carbon emissions that had troubled him in 2009.

Instead of tackling costs, Turnbull said last week he would legislate the Paris emission targets.

Only when The Daily Telegraph broke the story of Peter Dutton’s possible challenge did Turnbull begin to realise how far he had got it wrong.

On Monday he backflipped on the National Energy Guarantee.

“The NEG was the straw that broke the camel’s back,” Johnson says.

“This was meant to deal with the issue of cost and put the climate change issue to bed, finally. But he made so many concessions, virtually changing his position every day, it made people doubt him, his convictions and his judgment.”

Stripped of his conviction and hostage to his rivals, Turnbull was rolled with no credibility left.

His legacy from his refusal to leave office with good grace is a fiercely divided Liberal Party that will take a generation to fix.

Rolfe says history would not judge him kindly.

“He has got to be ranked among our lower levels of prime ministers,” he says.

“On a par with John Gorton.”

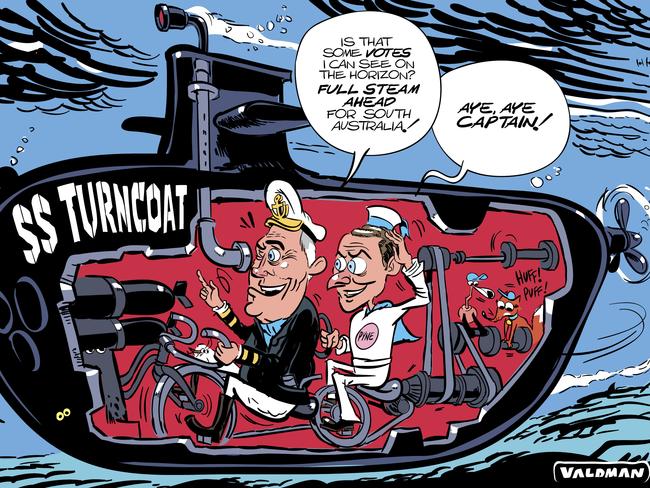

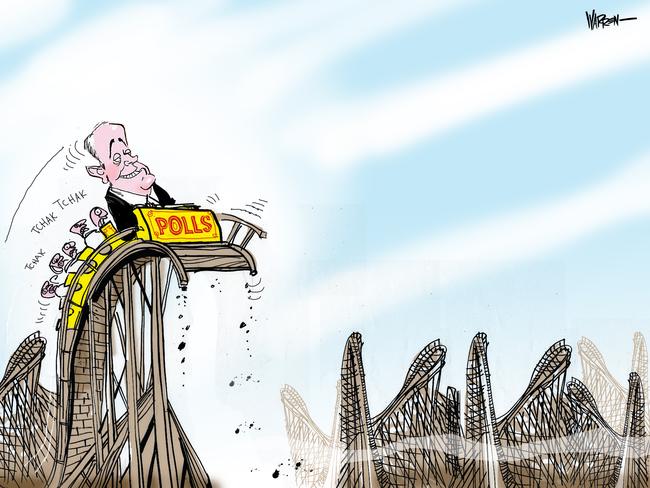

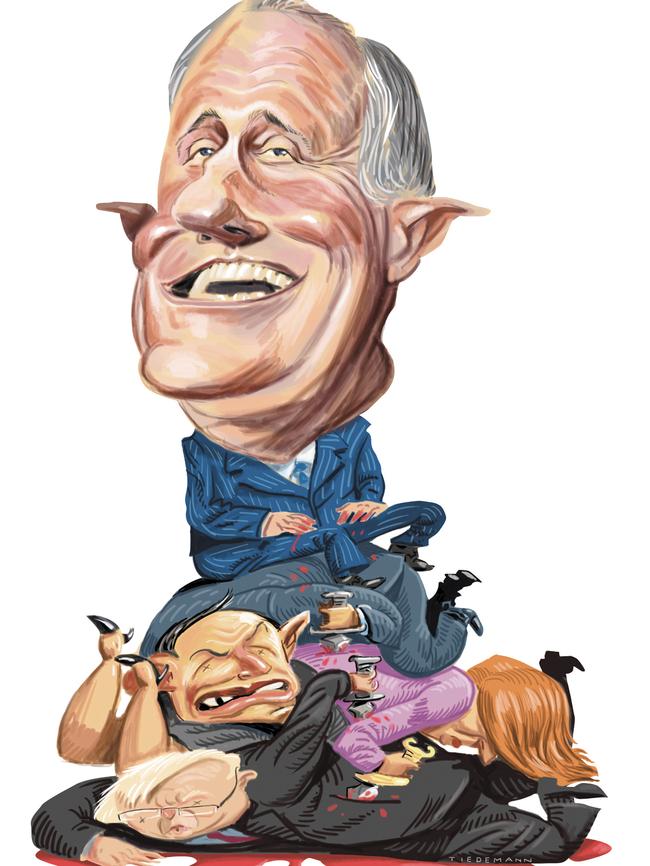

DRAWING A LINE UNDER THE PM

BY WARREN BROWN

With a revolving door mercilessly churning through five prime ministers in five years, it’s been a wild ride for Australia’s cartoonists too.

The conga line of PMs disappearing lemming-like over the cliff — one after another — has sure been fun to draw, but just when you think you have a prime minister’s face just about right, they’re unceremoniously turfed out and you’re faced with a new one.

Just like that.

Of course Rudd, Gillard and Abbott had their own visual idiosyncrasies — Rudd’s head a blond-topped soccer ball, Gillard’s nose like an ever-growing buccaneer’s cutlass, and the instantly recognisable, irrepressible red budgie smugglers of Tony Abbott were all cartooning shorthand for readers.

Yet Malcolm Turnbull’s arrival offered an altogether different challenge.

While he had not been in federal politics as long as some, Turnbull had been a fixture on the public landscape for decades — famous as the Spycatcher defender, a compatriot of Kerry Packer, an internet tsar, head of the Australian Republican Movement and, of course, as a super-wealthy merchant banker.

It was this, his reputation as a squillionaire eastern-suburbs silvertail, that cartoonists leapt upon — Turnbull was often drawn as the Monopoly man, ever-preposterous in a shiny top hat and wearing tails and spats.

In many ways he was a comical conundrum — a pompous, avowed anti-monarchist who styled himself as Australian royalty. Indeed the first cartoon I drew of him was as a self-admiring Louis XIV, replete with a vast, ridiculous, boofy white wig, a gold cape, stockings and buckle shoes.

On publication it filtered back to me — via my editor who’d just copped an earful over the telephone — that Turnbull was apoplectic at my depiction of him.

Music to a cartoonist’s ears.

Then, in the lead-up to his well-contrived putsch against Abbott, Turnbull reinvented himself, entering a ludicrous phase of wearing a black, open-neck leather jacket — reminiscent of George Lazenby’s one stint as James Bond.

This was the all-new, super-groovy, inner-city, hip Malcolm Turnbull who’d swan onto the set of Q&A and woo the anti-conservative lynch mob in whichever manner he wished. From a cartoonist’s perspective, it was rolled gold — in a leather jacket.

But in whatever form Turnbull presented himself, there was always a consistency in his face — perhaps from his theatrical days at the Bar — he had the ability to maintain a fixed smile even if his fingernails were being torn out with pliers.

I found this to be a remarkable signature feature of Turnbull’s — I once drew a cartoon about this particular peculiarity, where there were “The Many Expressions of Malcolm Turnbull” — happy, sad, angry, surprised — and every face was identical, sporting that grimacing smile formed from Araldite.

Will I miss him? I’ll miss him like I miss all the other PMs who fell before him, and like all Australians wait for the next PM. It’s like waiting for a bus.

I’d better get on with practising Scott Morrison before the next prime minister arrives ….