Why Voice to Parliament ‘has to work’

Despite being against the referendum, a prominent Indigenous Australian leader has revealed why a Voice to Parliament “must work” if Aussies vote ‘yes’.

National

Don't miss out on the headlines from National. Followed categories will be added to My News.

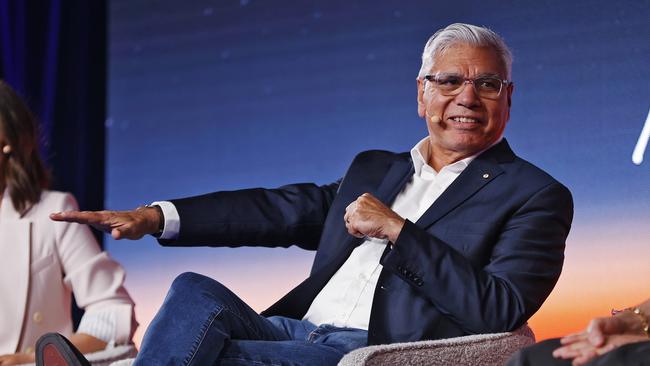

A prominent Australian Indigenous leader, Nyunggai Warren Mundine, has made a stunning admission while debating the merits of Voice to Parliament on Tuesday.

Mr Mundine, an outspoken opponent of the latest push for Indigenous constitutional recognition in policymaking, said should Australia vote ‘yes’ at an upcoming referendum – he would be all in to ensure it doesn’t fail.

Some of Australia’s top Indigenous voices engaged in robust debate about the latest push for Constitutional recognition and a permanent Indigenous Voice to Parliament at a Tuesday forum.

The Beyond ’23 event hosted by News Corp heard a range of voices both for and against the Voice to Parliament – which hopes to see a body enshrined in the Constitution, enabling Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to advise parliament on policies and projects impacting their communities.

The panel consisted of politicians and advisers on Indigenous affairs for the Abbot/ Turnbull governments Nyunggai Warren Mundine, Director of From the Heart Dean Parkin, Aboriginal academic and commentator Dr Anthony Dillon, And Hannah Hollis, a descendant of the Northern Territory’s Jawoyn people and Fox Sports host.

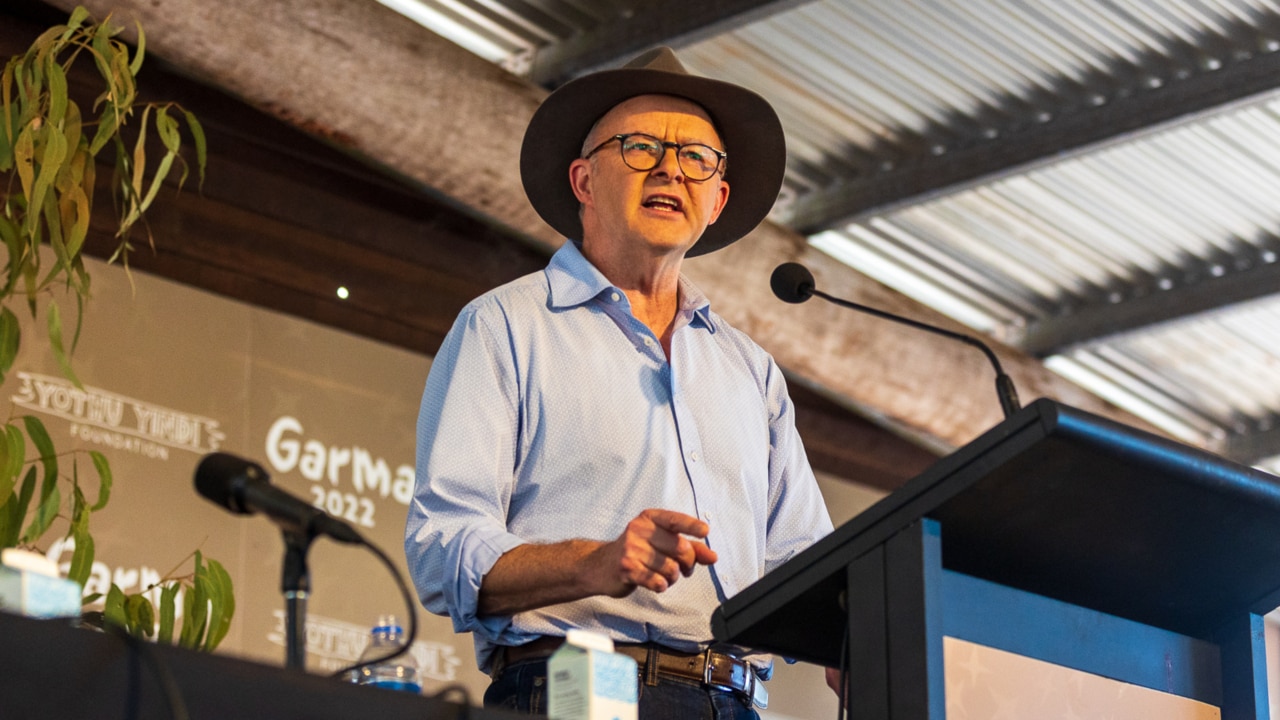

The Albanese Government has pledged to hold a referendum during this term of government to implement an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice in the Constitution.

The First Nations Voice will be an independent, representative advisory body for Indigenous people, which will provide permanent means to advise the Australian government on the matters that affect them.

In September, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese confirmed that the referendum will be held between July 2023 and July 2024.

The Referendum Working Group — made up of over 20 Indigenous representatives and the Referendum Engagement Group, another 40 First Nations representatives — will help guide the timing, question and education campaign surrounding the referendum.

Of the panellists, Mr Parkin – an advocate spearheading heading the Voice to parliament campaign – and Ms Hollis were in the ‘yes’ camp.

Mr Mundine was for voting ‘no’, believing the Voice did not have a strong enough focus on the “economic prosperity” of Aboriginal communities – which he believes is integral for closing the gap. He also thought Indigenous Australians were already significantly engaged with the government and industry.

Dr Dillon said he was yet to “outright dismiss” the notion but could not see enough detail to gain his support.

The battlelines

For Mr Parkin, the Voice means “practical recognition” of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

“We’ve been talking about recognising Indigenous peoples in the constitution for decades now,” he said.

“It wasn’t until the Uluru statement from the heart when Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were asked [what they want]; “We said, for the recognition to be meaningful, it has to be practical.

“It has to be about addressing the issues that face many of our families and many of our communities across the country. So this is a very, very good deal for Australia.”

Mr Mundine, who has first-hand experience in raising Indigenous issues through government, described an “evolution” of Indigenous involvement in policy since the abolition of discriminatory laws in the 20th century.

“I don’t know any race of people or any group of people in the world who did not get out of poverty and build a good nation without economic prosperity,” he argued.

“That’s the thing that I want to focus on … But I don’t see governments being an answer to that. I don’t see governments driving [that] forward.”

With his wealth of experience as a politician and Adviser for both Labor and Coalition governments, Mr Mundine claimed Indigenous Australians were already well represented in the halls of parliament and the business sector.

“I think it starts on the wrong premise that Aboriginal people don’t have a voice, but in actual fact, we’ve got a voice,” he argued.

“I go to Canberra every couple of weeks, and I’m tripping over black fellas – there’s heaps of them there,” he said.

“I’m a big supporter of First Nations and about having those First Nation conversations and then being empowered.”

He said the economic prosperity would come from “lifting government off Aboriginal people” rather than further embedding themselves with it.

What will the Voice to parliament look like?

For Dr Dillon, a lack of clarity about what the Voice would actually look like in practice proved a central sore point. He feared it had the potential to become a “machine for mindless rhetoric” about the need to “acknowledge the past” rather than move forward.

“I have a problem with this when people say: “We cannot move forward and we need to acknowledge the past,” because indeed, many Aboriginal people have moved forward,” he said.

“Will it be focused on helping the most disadvantaged Aboriginal people and not see Aboriginal people as a homogenous group?” he asked.

Is the Voice a bureaucracy-buster?

Pressed by his fellow panellists on whether or not the Voice will have practical application, Mr Parkin pointed to the Native Title Act as a prime example of economic policy that could improve. He said while the Act has provided security to the nation’s resources and “immense wealth” to First Nations people – ticking Mr Mundine’s economic prosperity box – it is also a fraught and “convoluted process” with a giant web or red tape.

“So it’s possible to create economic opportunity under things like the Native Title Act, but when it comes to being able to get a loan, insure your home on Native Title lands, it’s impossible in many situations,”

he explained

“It’s very, very difficult to leverage the opportunity.”

“The Voice would absolutely be important and sitting down with the federal government and making sure that the overarching legislation is actually conducive for those practical outcomes on the ground.

“There is a very big difference to what the legislation says it’s aiming to achieve, but what is actually practical and achievable on the ground.”

He said too often, well-meaning city bureaucrats and lawmakers miss the mark when tailoring policy for First Nations communities.

“It is impossible for them to understand how these things actually work in places like Aurukun, and Halls Creek, and Alice Springs,” he said.

“They just don’t understand the impact of the decisions that are made so far away from these communities.

“They need the input from the people on the ground who know how these things actually work.”

“From the time that money is announced at the top, you get a trickle down the bottom.

“And there are layers and layers of bureaucracy and other structures that soak it up along the way. We’ve got to change that.”

The Voice has to work

Even Mr Mundine, the most vocal opponent on the panel, agreed the Voice “has to work” if Australians ultimately vote yes at the referendum.

All panellists agreed the failure of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission, an involvement process established in 1990 and disbanded in 2005, put pressure added pressure on the Voice to be a success.

“If the people of Australia want to go down this path, then I’m really happy to sign up to make it work. Because it has to work. We can’t have any more failures,” Mr Mundine said.

“If Australia is not ready now then when? Ms Hollis added.

“There’s a movement happening in this country, 15 to 20 years ago - this would have fallen flat in the water.”

The end of a “very long journey”

Despite some rhetoric from the panel about Indigenous involvement already existing in politics and business, Mr Parkin said it had done nothing to close the gap – but a Voice will.

He likened the Voice to how governments in Australia and abroad handled the Covid-19 pandemic.

Governments, and to an extent, businesses, enlisted the help of health professionals as the virus took hold of the world – which posed the question; why doesn’t the government do the same with issues facing Indigenous Australians?

“So bring the expertise of our people who know how it works,” he said.

“They’ll be making [policy] with more intelligence and more wisdom about how it actually works. And where we can actually get that investment targeted to where it really needs to be.”

Mr Parkin said, as for the lack of detail, said there was “quite a bit of time between now and the referendum”, but the key was to get it right and not rush.

“What we don’t want to do right now is overwhelm people with loads of information because people that don’t know a lot about Indigenous issues, and what’s happening in our communities, it can be too much.

“We have been on a very long journey to get to this point. And there is plenty of time between now and the referendum itself.”

Originally published as Why Voice to Parliament ‘has to work’