Wartime exploits of Qantas founder Hudson Fysh revealed in Grantlee Kieza’s new book

He almost killed Lawrence of Arabia and was dubbed a ‘Tiger’ for his extraordinary wartime exploits – then this man changed the way all Aussies see the world.

National

Don't miss out on the headlines from National. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Hudson Fysh was an unassuming man who survived the horrors of Gallipoli and cavalry charges in the desert to become a decorated World War I hero in aerial combat. He learned about flying aircraft while dodging German bullets high over Palestine and flew secret missions for Lawrence of Arabia.

After the war, Fysh started a small airline in outback Queensland with two flimsy biplanes. He called it the Queensland and Northern Territory Aerial Services – QANTAS – and insisted his staff put safety and customer service above all else. He was still the boss almost 50 years later when the airline ordered its first shipment of jumbo jets that revolutionised the way Australians saw the world. This exclusive extract from a new biography by GRANTLEE KIEZA goes back to Fysh’s early days in the air.

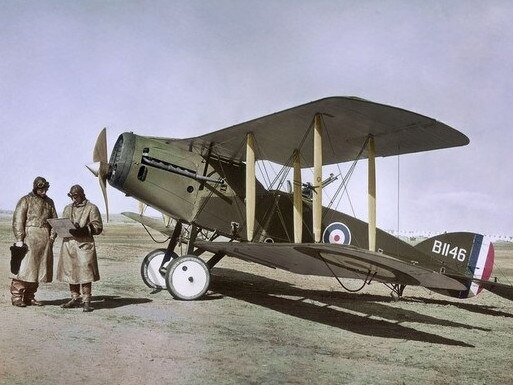

IN DECEMBER 1917, No. 1 Squadron of the Australian Flying Corps based in Palestine received the first of their new Bristol Fighter aircraft, making their previous war planes look like ancient relics.

Although the pilots were still exposed to the elements in open cockpits, Lieutenant Hudson Fysh, a shy but tenacious young airman from Tasmania, came to call these new F. 2 machines “the cavalry of the clouds”.

They were revolutionary weapons with double Lewis machine guns on Scarf mountings in the rear, and a Vickers machine gun firing forward.

Fysh had volunteered to serve in World War I as soon as the call for volunteers was made, and he was in the thick of the action on Gallipoli and then as a Light Horseman in cavalry charges in Palestine.

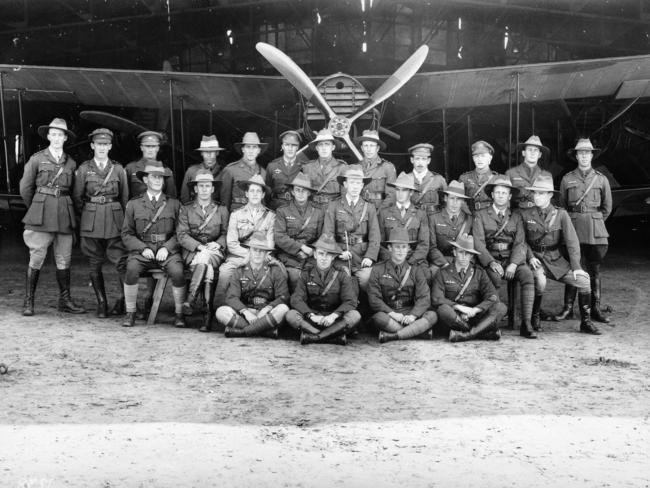

Since its beginning, No. 1 squadron had enlisted airmen from the Light Horse, believing that skilled horsemen had many of the qualities of good pilots, with their sense of balance and their cool heads in a crisis. The dexterous hands and instinctive touch required to ride a fast horse were seen as precisely the skills a pilot needed when handling an unpredictable machine, bucking and swaying as they did in the wind and under enemy fire.

The Bristol Fighters were crewed by two men – a pilot, who used the forward machine gun, and an observer such as Fysh who read the maps, took spy photos and used the rear machine gun.

It was the duty of each crew to prevent enemy aircraft getting back to their base with photographs and scouting information. Fysh was such a crack shot that he could hit an enemy machine at 400m when the accepted range was just 100m.

German aircraft would climb to great altitudes, and Fysh often found himself flying at 16,000 feet (almost 5000m) without oxygen. Despite thick coats and boots he would sometimes feel like “a dead icicle”, his thumbs so frozen that he couldn’t pull the triggers on his two machine guns. Still, on January 25, 1918, Fysh was part of a raid made by six aircraft on Kerak, about 25km east of the Dead Sea.

Two months later, Fysh joined missions bombing the Hedjaz Railway and a large viaduct southwest of Amman in heavy rain and even heavier ground fire. At noon on March 27 he was operating the rear machine guns on pilot Sidney Addison’s Bristol Fighter when they found three groups of Turkish cavalry, of about 250 men each, in the hills southwest of Kutrani. They flew low over the ancient crusader castle of Kerak; seeing Turkish cavalry in the courtyard, they dropped an 11kg bomb right in among them.

Later, when T.E. Lawrence of Arabia visited Fysh’s squadron at their new base in Ramla, Lawrence told Fysh he had been at the castle in disguise when the bomb dropped, and it had created carnage. Later Fysh would fly on secret missions for Lawrence.

There were no parachutes in the desert war, partly because of a belief that they might encourage crews to bail out too quickly. But fire in the air was terrifying, and some men jumped to their deaths rather than stay with a burning machine. Fysh once watched from the ground as the pilot John Walker and his observer Harry Letch took on a German LVG aircraft and made the fatal mistake of attacking from above and behind in full sight of the Germans’ rear gun. The Australians took a fusillade, which set their Bristol on fire. As plumes of black smoke billowed from their aircraft, the Australians jumped at 8000 feet (more than 2500m), and Fysh and others watched stunned as the two helpless airmen rolled over and over before crashing into the ground.

The small and wiry Victorian country boy

Paul“Ginty” McGinness became Fysh’s favourite pilot. Fysh regarded McGinness as an airman “full of dash and adventure”, and said that in his seven confirmed victories – scored when the enemy was shot down – McGinness was hit only once, when a bullet went through the tail of his machine.

Fysh and McGinness had both fought at Gallipoli. McGinness was with the 8th Light Horse, who were massacred in their charge on the Nek – he was one of the few from a group of 150 to survive the assault in the first line of attack. Bullets tore through the edges of his uniform as he ran towards the enemy guns. One skidded off the double webbing that held his pack, and another skidded across his hip, knocking him off his feet. His head hit the ground hard, and he fell unconscious.

Because he was lying in a shell crater, it appeared to the Turks that he was dead. When he came to, bloodied and badly sunburnt, McGinness stayed perfectly still until it was dark, then he crept back to the Australian lines. His bullet wound caused him kidney problems for the rest of his life.

On March 16, 1918 McGinness joined Fysh at the No. 1 Squadron. He had a forceful, engaging personality, a thin face, wavy fair hair, and grey eyes that saw far into the future when the life expectancy of airmen was measured in days and weeks, not years. He was as outgoing and garrulous as Fysh was reticent, but his mother had assured the military that he was “without a vestige of swank”.

In their first dogfight together, McGinness and Fysh encountered four German Albatros two-seaters over El Afule. Fysh fired a long burst at one aircraft as it flashed past but could see no effect, when McGinness made a sharp, wheeling manoeuvre and was on its tail, diving fast, his front gun flat out. The Albatros returned fire, and hot lead rocketed past Fysh’s head.

Then the Albatros, seemingly out of control, surged up in a towering loop with McGinness sticking to it and blasting away with his machine gun through the propeller. Instantly Fysh and McGinness were upside down. Fysh’s head spun. The inverted machine seemed to hit 300km/h. They were still upside down when McGinness shot the two-seater at the top of its loop, the Germans plummeting straight into the ground, their machine exploding.

Fysh had what he called the tensest thrill of his life on August 14, flying with McGinness over Jenin aerodrome. He looked up to see a formation of six German Pfalz scouts 2000 feet above the Bristols that McGinness and another Australian were piloting.

A climbing race began for the height advantage. When the enemy realised they were being out-climbed, they dived in formation at the two Australian machines. McGinness deftly dodged them, and Fysh counterattacked with his machine guns. All six Pfalzes were shot up and forced to land.

Many of the Australian fighter planes had been donated by wealthy benefactors. The pilots were not especially superstitious and flew many dangerous missions on Friday 13, but there was always a degree of reticence among them when they had to fly a Bristol presented to the squadron by a firm of Sydney undertakers.

From mid-August, the Bristol that McGinness and Fysh flew most often was C-4623 – also known as Australia No. 20 – which had been paid for by the wealthy grazier Sir Samuel McCaughey (pronounced McKackie) and his brother John. Irish-born Sir Samuel, then 83, had acquired more than a million hectares of Australia, and Fysh and McGinness shot down three enemy planes in their first mission on his aircraft.

On 30 August 1918, Fysh was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross and a citation that read: “His Majesty The King has been graciously pleased to confer the above reward … in recognition of gallantry in flying operations against the enemy.” It described Lieutenant Fysh as “a skilful observer, conspicuous for courage and determination, whether engaging the enemy in the air or attacking ground targets. He has taken part in numerous combats resulting in loss to the enemy and has inflicted serious damage on hostile camps and aerodromes”.

Fellow observer Clive Conrick wrote in his diary that Fysh “came in for a lot of congratulations” from all at the squadron as he was “a very popular and unassuming bloke”, later remarking that while he was usually mild-mannered, Fysh was one of the “Tigers” of No. 1 Squadron, known for always looking for a scrap in the air while some preferred to fly “Strategicals”.

On the afternoon of August 31, 1918, Fysh and McGinness and another two-man crew were flying at 14,000 feet near the Ramla aerodrome. They were alerted by their own anti-aircraft bursts that enemies were close by. The Australians powered in among the white puffs made by the Australian guns, and they challenged a pair of two-seat LVG reconnaissance aircraft. The enemy had to be prevented from returning to their aerodrome with photographs of English General “Bull” Allenby’s preparations for what would be the final battle of the war in Palestine – the Battle of Megiddo, also known as the Battle of Armageddon.

McGinness put Fysh in position under one of the LVG’s tails to blast away and send it into a vertical dive. The Australians watching the duel from the aerodrome applauded as the German pilot and his observer crashed head first inside the Australian lines a few miles from the Ramla airfield. When the engine failed on the other Bristol, McGinness attacked the second German machine from below. Fysh let them have it with both barrels, shooting them down too. The fuselage and wings on the port side of the enemy machine fell to earth in one direction while the two starboard wings floated off in another.

A cheer went up as Fysh and McGinness taxied home and pulled up in front of their hangars. The pair went out to examine the wreckage of the first LVG and found papers on the German officers showing they had been paid in gold the day before. But the gold was missing, and Fysh presumed the Light Horsemen had arrived before them. One of the Light Horsemen came to Fysh and handed him a cigarette case belonging to one of the Germans. It remains with Fysh’s family today. It was a sobering experience to attend the funerals for the two German officers in Ramla’s military cemetery.

In spite of their contrasting personalities, or perhaps because of them, Fysh and McGinness had shown they formed a perfect working relationship. On September 14 they took part in the destruction of a German Rumpler aircraft near Jenin, and the enemy rarely took to the skies again over that part of the front.

With the war all but finished, McGinness and Fysh were flying over the German aerodrome in Aleppo, at an extremely low altitude, when McGinness saw a German shell on the ground opposite the hangars.

Much to Fysh’s horror, McGinness landed and jumped out of the Bristol, then grabbed the shell and put it in the aircraft as a souvenir. He took off before the stunned Germans realised what had happened.

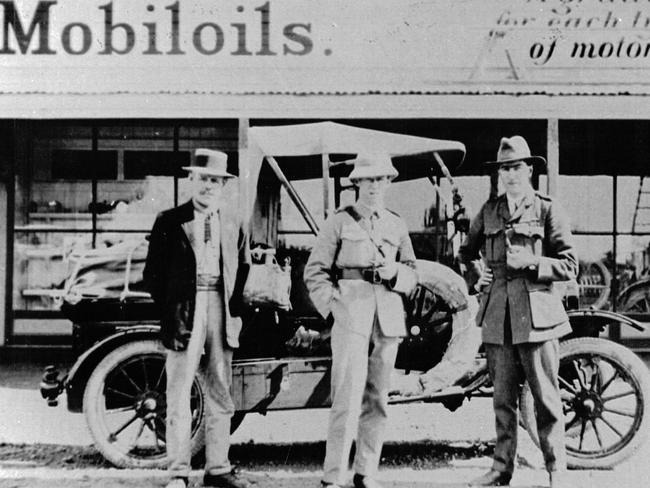

Three years later Fysh and McGinness, with the support of some graziers in western Queensland and the Northern Territory, launched their little bush company, the Queensland and Northern Territory Aerial Services – QANTAS.

They hoped to interest people living in remote areas to use aviation to overcome the tyranny of distance.

To save money, Fysh lived in a tin shed behind a Longreach garage and poured whatever money he made back into the business, later writing a booklet on ethics for his staff, insisting that safety and customer service would be the hallmarks of their little aerial venture.

McGinness, the maverick fighter pilot, quickly gave the business away, but diligent and determined as he was in the war, Fysh stuck to his guns and kept Qantas in the air through tough times.

He was still running the airline almost half a century later when Qantas passengers could travel across the world in a single day aboard the company’s fleet of jet aircraft.

This is an edited extract from Hudson Fysh by Grantlee Kieza. It will be published by HarperCollins/ABC Books on November 16 is available to pre-order now.